Johnny Herbert

In this interview by Johnny Herbert, Tron Meyer and Kent Fonn Skåre offer perspectives on their multi-faceted practices within art, craft, design, and architecture.

Approaching its fifth installment, the Norwegian Presence 2019 exhibition in Milan taking place from 9–14 April is an initiative operating within the dense entanglement of design, craft art, and other 'fine art' art practices. It is increasingly apparent that certain practices within this entanglement have, amongst other things, a very singular opportunity to complicate the pervasive ‘Scandinavian Design’ export and its branding and historicising of countries and the region. Within Norway, the particular mixture of shifting histories with institutional bodies and practices identifying with specific fields has led to, using the example of "applied art" and "craft art", roles being inverted: ‘craft artists are making prototypes for industrial production, and designers are creating unique objects and exhibiting them in galleries.’1

What is often been called “expanded practice” is becoming more and more prevalent. For example, one participant in this year’s exhibition, Tron Meyer, is presenting work as a "craft artist" and a "designer"; however, this is already far too reductive a bracketing, as he himself puts it when describing his current activity:

‘Right now, I’m working on commissions and self-initiated projects that go in every direction of what we might call architecture, design, and art. I struggle to balance the various scales and genres and what they in different ways demand as a process. Ideally things would be more structured, but maybe I will look back at this period as a very positive time if I find a more "fixed position" in the future. I think I will always complain that I don't have enough time for painting.’

In between emailing responses to questions, he is busy on site working on a large staircase project for Risa Meyer, the design firm he founded with Therese Meyer in 2014:

‘We are doing some larger staircase projects for both public and private clients in Norway and abroad this year. These are projects that take a lot of time to plan, manufacture and install, so, as it’s more or less only me at this moment, they are demanding to run. The final result is hugely rewarding; one of them will be within a larger public school, hopefully to be enjoyed for many generations to come.’

The ‘change of scale and method’, when working for a forthcoming exhibition in Basel and Norwegian Presence in Milan, enables him to enjoy a production process that is ‘more hands on.’

Meyer spent five years studying visual art, in which he had two to three years of ‘sincere interest and investment in drawing and painting’ before in the last two years moving towards ‘a more varied approach to art.’

‘I started placing my work into constellations, summing them up as installations. As I got more into the art world, I had a problem with how I could work as an artist from my studio and applied to study architecture the same year I finished my Master of Fine Arts. After studying and working for variously sized architectural offices for five to six years, I started working with my own projects.’

Given that education in many places now involves the pressure of fitting oneself out as quickly as possible for a career in the world as it is (according to a particular market) rather than realising each student group as a varying disruptive or catalyzing force in a current field, Meyer, unusually, didn’t consider the traversing of fields as particularly difficult, perhaps a testament to the steadfast importance of “the new” in the creative arts:

‘I really never made a decision to do a lot of different work. I started out with art, moved on to architecture, and along the way always made drawings of furniture I would like to build, primarily for myself.’

Another participant at Norwegian Presence 2019, Kent Fonn Skåre, prefers not to see his work as moving from one thing to another, particularly citing working methods: ‘Making physical books is much like making a sculpture, its form, material, content: it’s tactile, it has a feel to it.’

Having initially studied visual communication, he then continued onto the MFA program at Konstfack in Stockholm and now considers his practice fundamentally as sculpture. However, he also runs Gruppepress, ‘a publishing company which makes artist books, both for myself and other artists.’ This work has also included catalogues for exhibitions, but he doesn’t necessarily regard this work as part of his practice ‘in the same sense,’ citing the main difference as ‘authorship and context.’ He also identifies a correspondence between his interests in bookbinding and materials, making work with sculpture “natural” for him:

‘Paper was my first introduction to materials, a new medium with new considerations I found more intriguing than the field I was operating in at the time. Thus, bookbinding was my introduction to working physically with materials and form—this experience guided me towards other artistic pursuits.’

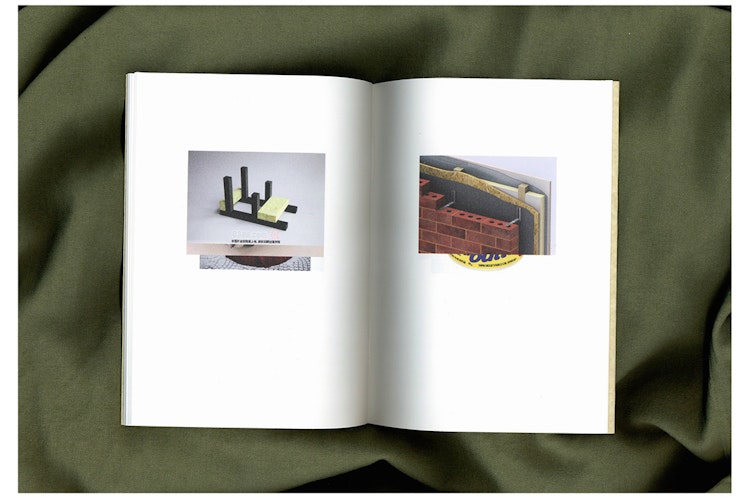

A crucial aspect of Fonn Skåre’s work is that he sees his whole practice as sculpture, even though he works across media and “categories”. As an insight into his sculptural practice, by way of a publication, Scrapbook, he speaks of his use of books as ‘context tools in exhibitions,’ but also as ‘three-dimensional containers of two-dimensional surfaces.‘

‘Scrapbook is an attempt at solving my problem with articulating ideas developed through physical work in text format. The images are from various sources and relate to my work in different ways. Two images are juxtaposed on each spread. The juxtaposition is expanded "through" the book by arranging all the images in layers. This creates overlapping collages with repetitions and shifts in the image combinations. The layering of images tries to blend these two features together.’

An understanding of this work as integral to his sculptural practice as a whole is then succinctly articulated: ‘Scrapbook is "sculptural", but on the book’s own premises.’

When speaking to Meyer, he pointedly states that ‘the tension between categories’ is something that he wants to hold onto: ‘I prefer it when play and necessity become jammed.’ Function and (sculptural) form are the tricky elements to balance for him:

‘I find it a bit too easy to say you work with sculptural furniture if you ignore functional challenges, the same way a purely functional work without any personal judgment is straight out boring. I think it is a bit simple to work with a crossover, but leave out ingredients that make such a potent cocktail for developing work.’

When pushed further on this point, he clarified it:

‘What I meant was that if you work with design, let’s say furniture, and you lean on the sculptural part in such a way that the construction or functional use is reduced to having now relevance, it is not a crossover. What is left is a sculpture playing on the image of a chair.’

As an example of someone who he feels works through this juncture, and who he ‘revisits regularly, without any disappointments,’ he cites designer Enzo Mari and specifically the project Mari initiated in 1974, Autoprogettazione (roughly translated as auto/self-design, or selvutforming in Norwegian). Consisting of sets of simple instructions for building furniture with nails and wood and seemingly taking up the social project from Bauhaus whilst also anticipating Ikea’s effacement of socially-engaged design (by commandeering the work of other designers), for Meyer, Autoprogettazione is very powerful, ‘evoking a more or less emotional response.’ It is something about the intellectual precision and ambition of that particular work, and Mari’s work in general, that strikes Meyer:

‘The experience I get from his work is not about a banal knowledge transfer of particular technical details, functional tricks, or good colour combinations. What I find so beautiful about his work is that he takes these rather strict and moral projects and turns them into anything but boring and reasonable design. There is always more to it than just providing the "right thing". His designs pass on content in so many levels. That’s what really moves me in stark contrast to the reasonable designs sold at Ikea.’

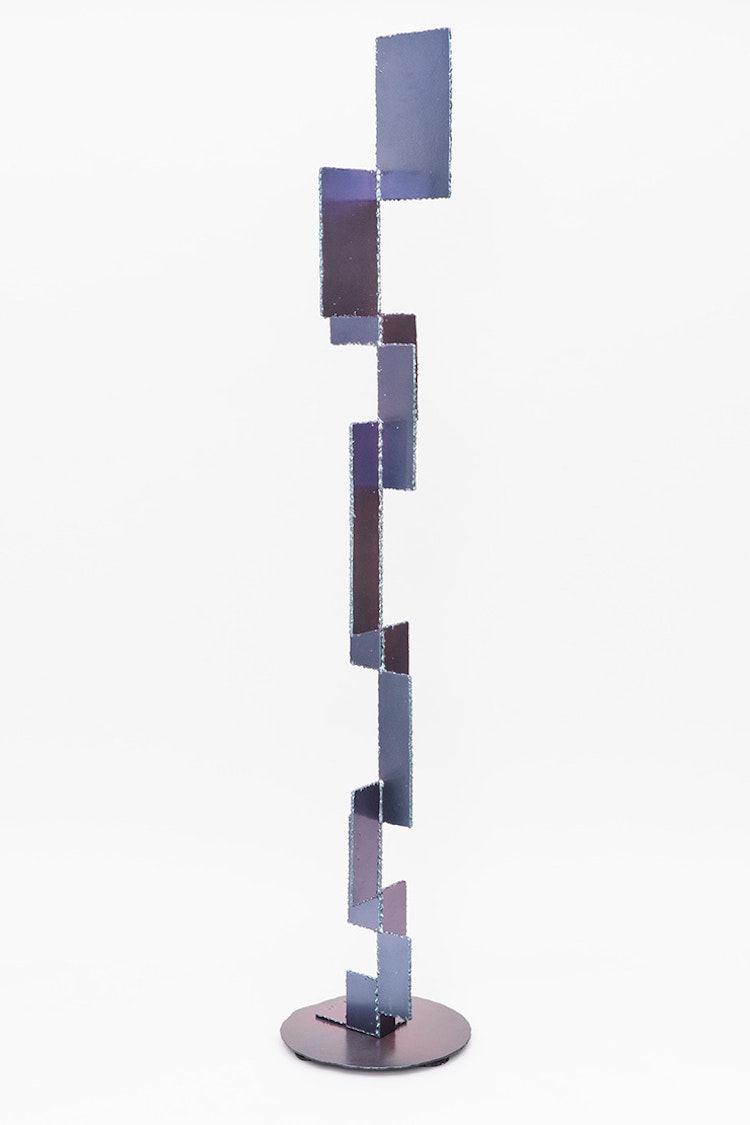

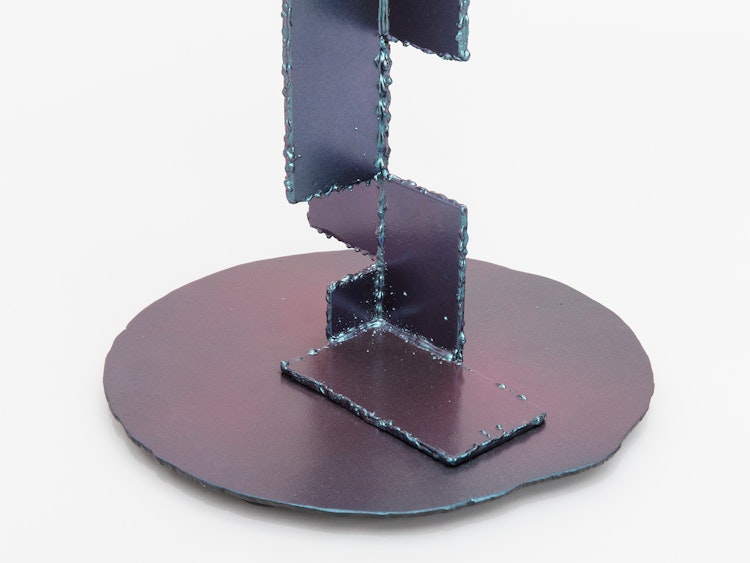

At Norwegian Presence, Meyer will present forms both with and without "functionality as a property":

‘The objects should give you an impression of how they are worked on and made into forms. With Cyclop I remove material to emphasize the connection point of the side table/stool, and with the Half Moon table a thin circular plate is bent to 90 degrees to obtain enough rigidity as a surface. The Varde sculpture is made from stacked stones where the original round shape is defined by the movements of the glacier over thousands of years; the stone is cut to expose the core structure of lava solidified some 290 million years ago.’

Fonn Skåre is also fond of simply worked materials but his particular material decisions introduce a different set of ideas. At Norwegian Presence 2019 he will show a piece of furniture from Universell, his furniture series made from ‘scraps of different stone slabs found in ditches, at construction sites, and outside closed down shops around Bergen. These discarded materials are like driftwood; I collect them on my daily commute between my home and studio.’ This specific use of found materials is important for him:

‘What they have in common is that they are natural materials that have been through different stages of a production process. Since they are off-cuts, their formal logic has been partially blurred. The weight, size, and shape of the scraps add certain restrictions in building that affect the result and user interaction— making the furniture somewhat "performative". This aspect is not a shallow attempt at being poetic, but a consequence of trying to find common ground between elements that needed to be resolved.’