Irene Snarby

Iver Jåks' artistic talent became obvious during a long period of hospitalisation following a reindeer herding accident in his youth, and he was admitted to the Sámi folk high school in 1950, when he was 18 years old. Set on becoming an artist he later attended the Norwegian National Academy of Craft and Art Industry and later the Art Academy in Copenhagen. His artistic practice incorporated Sámi duodji objects, materials, and techniques, in addition to drawing, large-scale sculptures and art in public space. In this article by Irene Snarby we learn about the life and art of Iver Jåks, and about duodji as a contemporary art practice.

Iver Jåks1 (1932–2007) actualised his Sámi cultural heritage through contemporary art. With an experimental and playful treatment of duodji2, he gave a voice to Sámi creative methods, traditions, practice, and experience in an arena that had previously rejected duodji by classifying it as ethnography rather than art.

Jåks has been called a bridgebuilder between duodji and Modernism3, but can such an interpretation cause the understanding of his works to be limited by inappropriate classification and a linear concept of time which he himself rejected? What challenges are there to interpreting Jåks and his art in the early 21st century.

The Sámi people have traditionally focused on aesthetics in all of life’s activities.4 In everything from cups and knives to sleds, traditional clothing, religious objects, joik (a traditional form of singing), and behaviour, the idea was to live so cautiously that one left no visible trace after oneself. As long as aesthetics infused everything, there was no need for a concept of art. Duodji

was a descriptor for creative activity, and a concept whose scope was infinitely wider than art per se. Makers of duodji related to tradition and treated it as a guideline, but put their own personal mark on the objects they made, thereby ensuring development at the same time as they followed their own heart as well as tradition. In contrast to Modernism’s innovative art forms that advanced without taking the past into account, the Sámi were always aware that they built on the knowledge of their parents and past generations. They knew they stood on the shoulders of giants whose experience they could not manage without. They did not relate to a Western concept of art, but focused instead on the relation between a form and its functional value. Creativity was linked to a context that was both necessary and meaningful. Meanwhile, elsewhere in Scandinavia and the world, Western concepts of art, through Modernism, were used to cultivate non-purposive art.

A circuitous path into the artworld

Iver Jåks found inspiration for his distinctive installations at the intersection between ancient Sámi ideals and a concept of art that was both Western and modernist. The path that led him to this liminal place was both long and circuitous. When he was born in October 1932, on a mountain near Idjajávri (Nattvann) not far from Kárášjohka (Karasjok) in the Norwegian part of Sápmi, it was unthinkable that he would one day become an artist. He was born into a reindeer-herder family, and he had a happy childhood, learning early on how to use a knife, both to survive in the wilderness and to carve and make useful and beautiful tools. All this changed when he, at the age of eight, was seriously injured while riding a reindeer sledge. He ended up spending five years in hospital – throughout the whole of World War II. Afterwards, and for the rest of his life, he suffered much physical pain. He was forced to choose an occupation he could cope with despite his injuries. During the long period of hospitalization, Jåks had used drawing to communicate with the doctors and nurses who only spoke Norwegian. It was evident from early on that he had a talent for drawing, so he decided to become an artist. If Jåks had not been injured and forced to spend time in Norwegian institutions, it is doubtful that he would have been aware of this possibility. In Kárášjohka, his choice of career had a mixed reception. 20 more years would pass before a distinct word for ‘art’, dáidda, would be coined, and many people questioned whether being an artist could even qualify as an occupation.

From isolation to playful avant-garde

In 1952 Jåks moved to Oslo and spent the next three years attending classes at Statens håndverks- og kunstindustriskole (SHKS, the National College of Art and Design, Oslo).5 His time at the school, however, did not confirm to him that he should become an artist.6 In the 1950s Norway was still heavily marked by a strict policy to ‘Norwegianize’ the Sámi people. Many Sámis chose to hide their identity when they came to the capital city, and few dared to speak their own language in public. Sámi aesthetic objects, then as now, were only displayed in museums for ethnology and cultural history; they were not seen as possessing artistic qualities above and beyond those of decorative folklore. Jåks did not try to draw attention to himself but was a diligent and goal-oriented student. After SHKS, he studied for an additional year at Statens sløyd- og teiknelærarskole at Notodden (a national school for teaching woodwork and drawing), before returning to Kárášjohka. He was hired as a duodji teacher at the secondary school / college known as DSF (Den Samiske Folkehøyskolen). Soon after this, two Danes arrived in Kárášjohka who would turn his life upside-down. Inger Karen Johanne Nielsen had travelled from Roskilde to experience Sámi culture, and in her, Jåks found his future wife and colleague. His meeting with Inger and her contacts would be crucial for his artistic development. Inger had studied millinery and was deeply interested in art. The Danish art historian Rudolf Broby-Johansen also visited Kárášjohka around the same time, and through contact with him, Jåks was able, during 1957–59, to audit classes in fine art printing at Copenhagen’s art academy. He studied contemporary art history with Broby-Johansen, who at the time was interested in interpreting the world’s art in close relation to everyday life.7 While studying European pictorial art, Jåks began recognizing the distinctive character of Sámi art simultaneously as he gained insight into the uniqueness of his own background. He was inspired to explore his family history and Sámi mythology, both of which would come to affect the way he worked. In Copenhagen, Jåks encountered an openness and enthusiasm for non-Western art – an attitude that was typical for the avant-garde scene there at the time. Playfulness and an open-ended relation to art were important approaches that he carried further, at the same time as he continued pursuing the many possibilities he found in duodji.

Because duodji encompasses activities that are not only practical and social but also spiritual, for instance collecting materials from nature and processes related to Sámi epistemology and religious beliefs, it was, for Jåks, a boundless wellspring for creativity.8 The concept of duodji points to both the production of an object and to the object itself9, and it is one of the strongest indicators of Sámi identity. A duojár (a maker of duodji) relates to traditions that reflect deeply rooted collective values and norms as well as immaterial knowledge about processes and experiences with duodji. Amongst Sámis, there are always discussions about how duodji is practiced, with a view towards neither diluting it nor letting it stagnate. Jåks had a dynamic view about the path duodji should take, and he was concerned that it should not ‘freeze’ into memories about the past, but always be developing. He wanted to give his works relevant content as contemporary art and warned against limiting the way duodji was practiced; the rules should not be so strict that Sámi culture became fixed and frozen. If Sámis continue doing everything in the old way, he argued, they would “end up as a museal population and culture, living an exhibitionary life, but with no actual right to life”.10

The concept of duodji points to both the production of an object and to the object itself, and it is one of the strongest indicators of Sámi identity.

Friction as a driving force

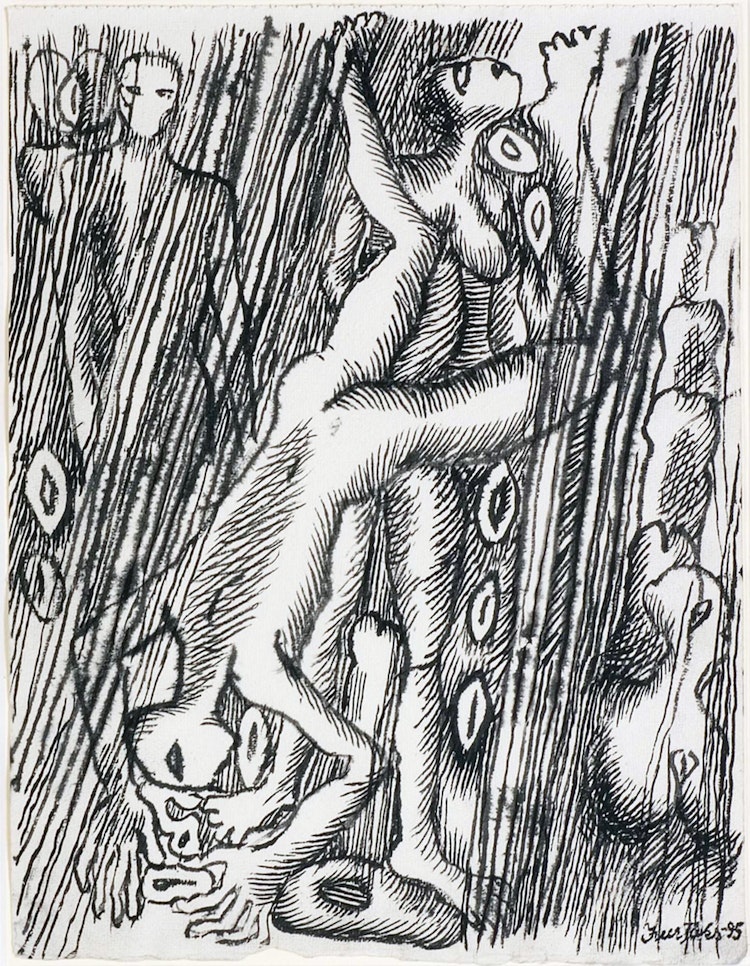

In the late 1960s the time was right for Jåks to become a full-time artist. He was the only practicing artist in inner Finnmark and, due to receiving a large public commission for the new Sámi museum in Kárášjohka – Sámiid Vuorká-Dávvirat – he had a unique opportunity to display his repertoire of motifs. The hefty and unveiled way in which he presented erotica and mythology was taboo in the pietistic environment he grew up in, but many viewers were delighted with his confrontation of double moral standards and the aesthetic qualities of his drawings. Ibmiliid dánsa (‘Dance of the Gods’, 1972), a wall relief made from cement, put Sámi art ‘on the map’ as it were, and still stands as a monumental door-opener into a mystical universe. The same can be said for the museum’s brass door handles, which might suggest an erotic coupling between a man and a woman, as well as the back side of a North Sámi drum. Jåks faced severe criticism from some terrified pietists due to the honesty in his works, but it seems to have had the opposite effect of its intension and functioned as an encouragement for him. Along with producing many public commissions, he also created, among other things, sculptures in diverse materials and sizes, printed art, book illustrations, and iconic drawings of voluptuous female figures engaged in sensual and frolicking games with our creator. Duodji’s roundish visual language was often an inspiring guideline, as seen for example in his impressive brass works Male Form and Female Form from 1973. Over time, however, he focused more on transformation, and by the late 1970s, his visual idiom and the processual aspects in his works were so innovative that few viewers understood what they were about.

Art historians who draw mainly on modernist references have often under-evaluated Jåks’s works by deeming their Sámi aspects as insignificant additions. A recent example of this can be found in a review of the exhibition Let the River Flow, held at the Office for Contemporary Art in Oslo in the summer of 2018. The art critic Line Ulekleiv, writing for the newspaper Klassekampen, criticizes the way in which Jåks’s work Bajás guvlui viggamin Sápmái duddjomat

(‘Upwardly Striving Sámi Culture’) is presented. She searches for a purer focus on the modernist Iver Jåks and feels disturbed by the traditional works that are exhibited alongside his work.11 Ulekleiv is not alone in her sentiments but follows a long tradition of art critics who are unable to accept a connection between the aesthetics of Indigenous peoples and that of contemporary art.

The Sámi Art Research Project at the University of Tromsø, underway since 2009, seeks to develop new theoretical perspectives and relevant discourses around different approaches to the art of Indigenous peoples, yet with emphasis on the field of Sámi art.12 It turns out that old modernist theories often surface when the researchers meet. A classic imperialist notion is the desire to constrain or freeze Indigenous culture in order to preserve it in as original a form as possible.13 Many studies of Sámi art have focused on a distinction between, on one hand, the autonomy of art, and on the other, the traditional knowledge linked to duodji.14 Jåks chose to exploit the friction between the two in order to promote a wide and holistic interpretation of duodji. He had a free and unstrained working practice, at the same times as curators, by the late 1970s, found it important to distinguish between pictorial art and duodji. After this, several young Sámis entered the north-Norwegian art scene, among others, those known as the Masi Group.15 For some of these newly-educated artists, it did not feel right that their art was associated with traditional folk art because they did not work along those lines. The concept of dáidda gained an ever-stronger foothold, and in turn pushed the understanding of duodji even farther away from contemporary art. Jåks, by contrast, became increasingly keen to visualize his cultural background by reclaiming the ancient understanding of duodji – without running it through the mill of Western interpretation. To his mind, creativity was closely connected to a deep and fervent respect for nature and a circular understanding of time.

Jåks encouraged transformation and decay and was therefore especially interested in organic objects and the ways they could be treated. He did not see conservation as positive, for it would ‘kill’ living materials. He could leave pieces of wood outdoors for years in weather and wind, then carefully cleave them with wedges, using no physical force. In ways such as this, he allowed organic materials themselves to lead the process of creation, emphasizing growth rings and knots in the wood in a natural way. After completing a sculpture, he could dismantle some of its parts and use them in other works. Nothing was fixed for all time. He repeatedly challenged curators to put together installations that were separated into loose pieces when they arrived at exhibition venues, and he rejoiced when the installations changed form.

Most of Jåks’s sculptures continue to undergo transformation long after his death. This situation poses a challenge for those who administer and care for them. When his house, studio, and storage spaces were cleared out after his death, those who performed the task luckily understood that what they found was not firewood. They kept the grey-painted pieces of wood that had been stored away. It was discovered that they belonged to two works: Cuippit (‘Stakes’, 1996) and Lea go, vai ii? (‘It is, is it?’,1997). Due to the fact that several pieces were missing, the works could not be re-created in the same way as the artist himself had made them. Nordnorsk Kunstmuseum (The Art Museum of Northern Norway) in Tromsø took possession of the remains of the works and, in order to include them in the exhibition Iver Jåks Reconstructed (2010), had the missing elements made from scratch with modern tools. Observing the new elements, it became clear just how long and meticulously Jåks had attended to each detail of his works. The new elements were roughly sawed – to the extent that the harmony and mystery in the works were disturbed. The case of Iver Jåks Reconstructed reveals how difficult it is to exhibit works with vital parts missing, especially when it is no longer possible to get the artist’s approval for a new exhibition under new conditions. So we can rightly ask: Should we just admit that a work has been lost, or can we patch and glue and pretend it still exists? At what point do we go too far, and do both the work and the artist a disservice?

A challenging inheritance

One of Jåks’s most distinctive works was initially placed in the woods near the Sámi high school in Kárášjohka. The artist intended for the 7.5-metre-tall wooden sculpture Runebommehammeren / Ballin (‘Holy Drum Hammer’, 1983) to decay gradually and provide nutrition for new trees and bushes. The sculpture was not meant to decorate the entryway of a square building, but to remind the students of the values associated with a lifestyle closely linked to nature. A path leading past Runebommehammeren had developed over time, as the students themselves walked out to the sculpture, and it testified to the fact that many people appreciated this quiet place in the woods. In 2015, however, a decision was made to relocate the sculpture, and those responsible for the school building and surrounding area could not prevent it.16 The school was to be expanded, and it was felt that the work of art needed to be secured. Trees and bushes that had been allowed to stand undisturbed and grow around the sculpture for 30 years were chopped down, and Runebommehammeren was moved to a well-manicured lawn.17 But something significant was lost along the way. It was as if all relation to the place, the process, and mythology were torn away for the benefit of a context stripped of Sámi content. That this could happen without any notable protest in Jåks’s home village gives cause for reflection. Has the ancient mode of thinking – a thinking that permeated the project that provided a context for the sculpture –been drowned and forgotten through years of Christianization and Norwegianization? Do people not recognize it, or do they not trust it to be interesting enough?

1: Iver Jåks, 'Ballin' ('Holy Drum Hammer'), 1981. Sculpture. Pine. Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design, Billedkunstsamlingene. © Jåks, Iver Iversen/BONO.

2–3: Iver Jåks: 'Ballin' (‘Holy Drum Hammer’), 1983. Picture from 2013. Public art work near the Sámi high school in Kárášjohka.

Concluding reflections

The cases mentioned above – of categorizing Jåks as a modernist, poor attempts to reconstruct missing parts of his works, and trying to preserve his works for posterity – show how challenging it can be to administer what we have inherited from such an innovative artist as Iver Jåks. The fact that we today are unable to prevent his works from such deterioration is a sign that Jåks is still ahead of his time, and our time, precisely because he took recourse in ancient epistemology. The thinking incorporated into his works stems from an immaterial knowledge that is poorly appreciated today. The elderly die, and with them, the sources for the unwritten rules saying one should not leave traces. The idea of not making art for eternity links Jåks’s works to the thinking of indigenous peoples worldwide. According to Professor Harald Gaski at UiT – The Arctic University of Northern Norway, indigenous aesthetics are characterized by a holistic approach to the way we live; it has salience in many of the main currents of social debate, particularly as regards human responsibility and the individual’s position in questions concerning the environment, the climate, and our continued existence on earth.18

The timeless aspects of Jåks’s art make him ever-relevant. Long after his death he continues to inspire artists of all ages. Few, if any, have managed to combine duodji and contemporary art in such a playful and seemingly natural way. There were no words for ‘sculpture’ and ‘installation’ in his mother tongue. But he was not preoccupied with terminology; he focused instead on the dynamics of his works, on transformation and processual aspects, and on raising awareness and understanding of the ancient and holistic worldview found in pre-Christian Sámi culture and elsewhere. Now that Modernism also appears to belong to the past, it is possible to see that Jåks, in addition to building a bridge between duodji and Modernism, also paved a way forward, through contemporary art, into the future.