matt lambert

In this interview, matt lambert converses with multidisciplinary artist Ahmed Umar on materiality, craft-based art, and how storytelling emerges as a form of activism in Umar's artistic practice.

Ahmed Umar (b. 1988) is a multidisciplinary artist who lives and works in Oslo. Ahmed came to Norway from Sudan in 2008, as a political refugee, and graduated from Oslo National Academy of the Arts in 2016, with an MA in ‘Medium and Material-Based Art’. In March 2018, I had the pleasure of participating in the day-long seminar Saying NO NO to Kantian Autonomy and Getting Jiggy with New Materialism, organised by Norwegian Crafts. This was part of a series of seminars hosted by the magazine Current Obsession during Munich Jewellery Week. The seminar dealt with practices that avoid or challenge a Western notion of art. It was there that I first encountered Umar’s work. I learned more about it when we both participated in PRAKSIS’s 9th residency Adornment and Gender: Engaging Conversation, which was produced through collaboration with Norwegian Crafts later that same year.

When I was asked to interview Ahmed Umar, to find out their thoughts about materiality, I was excited and challenged to think outside conformist ideas of ‘mono-material’ and what it means to master something. Umar’s works present complex stories that are not grounded in a Western worldview. They’re informative, shocking and revealing.

From a material and form-related perspective, Umar’s practice is quite broad. It disrupts stereotypical Western ideas of ‘siloed’ craft practices that focus on a single material or small group of materials and forms. Instead, Umar uses stories as a foundation for their works, selecting whatever materials work best to tell a given story. I would put forward that Umar takes a new materialist approach to art by recognising that materials are not passive but instead agential and active.

From working with Umar in the seminar, residency, and seeing their works, I see their way of working as offering resistance to the Western idea of what it means to master something. According to Julietta Singh’s text 'Unthinking Mastery', mastery as a concept is entrenched in colonialism: to be a master, one must have dominance over a subject/slave. In this way, mastery is positioned at the threshold of narrative and matter, which creates entanglement. Following Singh, Umar’s emphasis on working with materials – instead of using materials – could be seen as breaking away from the objectification and commodification of materials and the subject per se.

Using Singh’s theorisation of mastery as a lens, Umar’s works appear to challenge the idea of mastery, for their chosen materials shift between various works and projects, and the works prioritise gesture and story over control. What follows is an edited version of a conversation I had with Umar, in their studio at Kunstnerforbundet in Oslo, Norway, in the summer of 2019.

Much of your artistic practice deals with restrictions or working within them. Could you talk a bit about this?

‘True, in many of my works I discuss restrictions I’ve faced – those implemented by society or religion. I’m from Sudan, but I spent a big chunk of my childhood in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. During my upbringing, my family spent time in these two countries that, although sharing the same religion, have very different cultures. Both places have had an impact on my being and my artistic inspiration. It was very interesting at times, difficult at others, but overall an enriching experience that I’m very grateful for.

An example of the issues I address in my work is the confusion caused by differences between the religious teachings in the two countries. What you go through when you don’t know where exactly you belong. I demonstrated this through several projects, among them, a series of shows entitled ‘Forbidden Prayers’. The first instalment in this series is a show titled ‘Glowing Phalanges: A Prayer for Each Phalanx in My Right Hand’.

The project is based on a dilemma relating to the use of prayer beads. At school in Mecca, I was taught that using prayer beads to count prayers is heretical; it was claimed to be a serious danger that could compromise true belief. Meanwhile, my family, from the other side of the Red Sea, has a totally different approach. The family members are known for their devotion to Sufism and praying with large prayer beads. Some of them use a chain of one thousand beads.

The religious studies teacher tried to encourage the class to stop using prayer beads by claiming that if you instead keep track of prayers by using your right-hand phalanges, you will be generously rewarded by Allah. Your phalanges will glow and lighten the darkness of the Day of Reincarnation. The right hand, culturally speaking, is used for ‘good things’ like prayers, eating, shaking hands, etc. Each finger contains three phalanges/bones, except for the thumb, which has only two. But it is counted as three to for the sake of ease when counting to fifteen. There are fifteen prayers per round. The ‘Glowing Phalanges’ show consists of 15 prayers/sculptures and resin casts of each phalanx in my right hand.

At one point in my life, I wanted to save my family from what I saw as misguidance. All Muslims are urged by the prophet Mohammed to change whatever evil they see. He says: “Whoever amongst you sees an evil, he must change it with his hand; if he is unable to do so, then with his tongue; and if he is unable to do so, then with his heart; and that is the weakest form of Faith.” I therefore tried to voice my judgements, but I had no impact on the family members because they are so solidly entrenched in their own customs.

I still consider this Hadith – that is, a saying by the prophet Mohammed – as a starting point for prejudice, since it can be loosely applied to everything, and by everyone.’

Why did you choose resin for your prayer sculptures?

‘I’m very flexible when it comes to materials. I use whatever helps the story come across and be more sensible. In this project, I use several kinds of hard wood and bones, materials I’ve never worked with before. The choice of bones in combination with other materials is a direct reference to actual finger bones and joints.’

Where does craft sit then? Do you consider yourself a craftsperson since you have an MA in ceramics?

‘I have an MA in ‘Medium and Material Based Arts’. I made my graduation project in the ceramics department. But I haven’t really been keen to categorise or label myself. But if I really must, I would say I’m an art and craft artist. But it’s not really a concern of mine.’

Do you have access to ceramics anymore, or is it your intentional choice to pause from working with the medium?

‘No, I don’t have the possibility to work with ceramics in my current studio at Atelier Kunstnerforbundet because I don’t have a kiln. My ceramic projects have always been pretty large. So, as long as I don’t have a confirmed exhibition plan, I don’t think I will create pieces in ceramics. I’m not in a situation where I can work with an open budget. It’s expensive to make large ceramic pieces; the clay, firings, transport and then storage all cost money, and then of course I need to pay all my other bills too. I stored my Thawr, Thawra ( ثور، ثورة Ox, Revolution)’ sculpture for three years before it was acquired by the Norwegian National Museum. The cost of it all gives very little room for working intuitively.’

In the works of yours that I’m familiar with, there is a use of fragments or shards or pieces of things. Is this something you’re consciously aware of, or does it just happen? Looking at this piece (‘Would any of you love to eat the flesh of his dead brother?’), it’s like everything seems – broken isn’t the right word because it’s not broken, but it’s in fragments or it’s in pieces.

‘This is a cast of my full body in 29 fragments. The number of the fragments refers to my age at the time of making the work. It’s a literal interpretation of a verse from the Holy Quran that admonishes believers to stop backbiting or spreading rumours. Then Allah asks this metaphorical question that is the title of the work. I tell my story of being shredded online with rumours and hate, after opening up about my sexuality. This piece is a physical offering of my rotting flesh to whoever loves to feed on it.’

How important is it that the viewer, the participant, clearly understands that story?

‘I consider my artistic practice as a medium of storytelling and as a form of activism. This is why I want as many people as possible to experience it. I’m not a man of many words, but I want to change my life and the life of whoever relates to what I’m fighting for. I try to communicate through basic human senses and emotions. And I do see simplicity as a method to reach out to others. It doesn’t necessarily mean I’m opening everything up for the viewer; I leave some space for personal interpretation and creativity while keeping my own secrets.’

What do you want a participant or viewer to take away?

‘My side of the story. I want open discourse, especially on issues in which voices like mine are often compromised and unheard. For instance, the situation of the queer community in Sudan and how traditions and religion are continuously used against us. The same applies to women, or, let me put it this way: everyone except cis men in Sudan.’

Is there a risk of misunderstanding your work, or of exoticising it? How is your work perceived in Norway?

‘I don’t think it’s misunderstood or exoticised. It’s quite natural to stick out when you come from a different cultural background, but I don’t feel I’m given more opportunities than other artists because of my skin colour or background. Neither do I feel pushed to adapt to or adopt a certain direction or way of expression. I do my job, which is to make art. I can’t control the attention it receives and how it’s received. Norway has given me a chance to be completely myself.’

What made you decide to do the performance ‘If you no longer have a family, make your own with clay’?

‘I had almost no choice. I’ve never had the confidence to stand directly in front of people and perform or be the focal point. It’s really, really scary. I had to perform pieces that tell stories too personal to be performed by others, too tactile to be shows on a wall or in a glass showcase. It has also been a form of therapy for me.

The performance I’ve presented about ten times in different places around the world is now inspired by the Sudanese saying “If you no longer have a family, make your own with clay”. Taken literally, this means a lump of clay is better than a flesh-and-blood person who hurts you.

The first time I gave the performance, it was a process of letting go of the 223 friends and family members who, after learning about my sexuality, decided to respond with hate and disappear from my life. In a temple-like, quite atmosphere lit only with tea lights, I sit on the floor and create a visual expression of my feelings about these people by making clay figurines. Before each performance, I gather the audience in a different room in order to talk about the story behind the performance and how the members of the audience can apply the Sudanese saying to their own lives.

Over the years, the performance has taken different directions. Sometimes it deals with other themes I care about. One example is the massacre in Khartoum that took place in June 2019.’

How do you know when a work is finished or when it’s good?

‘When I feel I’ve given all I have and that my message is put across. For example, to secure access to my thoughts, I used some Sudanese local sayings that have been sources of inspiration for a few of my shows. The saying used for the title Carrying the Face of Ugliness is a case in point. This is one of the shows that is close to my heart; it’s also unique since it’s the first solo show not based on my personal story. It portrays eight LGBT+ people and allies from Khartoum. I secretly travelled to Sudan and met with these incredible people. I wanted to document this sense of joined forces. They stood in front of my camera with their face covered by my own, since there are fewer risks for me than for them because I live outside Sudan and my chances of making it out are higher.

Seven of the eight portrait photos were taken in less than 30 minutes. Because they were shot outdoors, I still remember that we [an LGBT group in Sudan] were very afraid we would get arrested and stuff like that.

The saying “Carrying the face of ugliness” is said to describe the member of a group who is the first to voice the group’s opinions. This person therefore takes most of the blame. In my case, I’m the first gay man from Sudan to publicly come out as gay in social media.’

Was there writing with that exhibition?

‘The main writing consisted of the interviews I made with the participants. The portraits were shown on 200 x 135 cm boards hanging from the ceiling, and the interviews with the subjects were printed behind their portraits. The interviews introduce the participants: who they are, what do they do, their role in their communities and how do they see their future in Sudan. I wanted to show who they really are – winners and fighters, not victims. I also provided some facts about Sudanese criminal law, which treats homosexuality as punishable by death, plus key information about the situation for the LGBT+ community in Sudan.’

Has there been a response from anyone in Sudan or from the people you worked with?

‘Yeah, the people I portrayed were very happy and pleased about the response and the critique of the show, both online and in the Norwegian newspapers. I think it’s a great recognition for all of us as a community. We, the participants and I, consider this show as a measure of progress. We hope that one day in the near future we’ll be able to pose together for a new portrait, with our faces visible and with no risk involved.’

Ahmed Umar, 'Carrying the face of ugliness', 2018. Photos by Ahmed Umar

How do you deal with the sense of responsibility that comes with all of this?

‘It’s a great responsibility to be out in front and have many people watching your every move. I try to keep my actions balanced, yet very true to my personality. What keeps me going is that I get a lot of fantastic and motivating messages from Sudanese people. They give me all kinds of support and love. I got a message from a 16-year-old who said he’s also gay and doesn’t feel alone anymore. He said he looks up to me. That freaked me out. I’m thankful to be what I needed as a teenager for a teenager now.’

How many messages can you reply to and still retain your sanity and do everything else you need to do? You’re the advocate and the resource for everybody who has questions, and you’re not being paid to answer their questions.

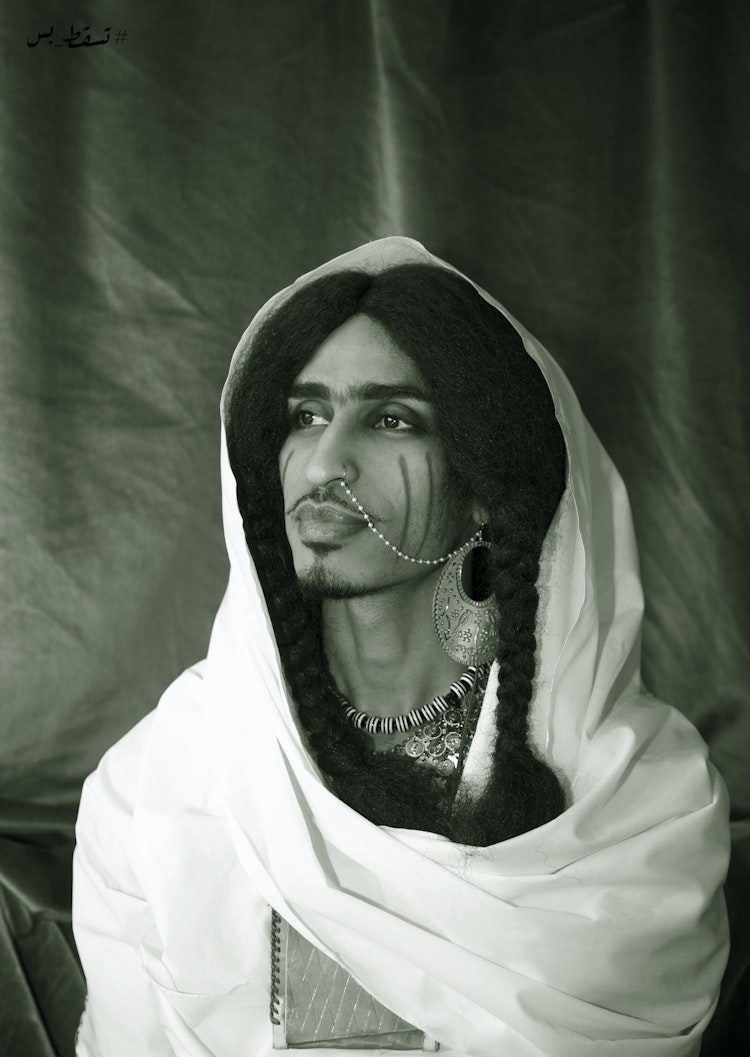

‘It’s exhausting. But I understand the situation since I went through it myself. You really need help when you reach out to someone you don’t know; you’re seeking comfort and answers about your body and sexuality. I therefore have a strong feeling that it’s my duty to make things easier for people who need me, when I can. And I force myself to take breaks every now and then in order to relax my head and rearrange my ‘shields’, so I can face another round of hate and bullying that follows my online exposure. The most intense period was after posting my portrait #White_March in 2019. This is a self-portrait of me wearing traditional women’s clothes. I introduced myself as gender-fluid. It was my contribution to the call for visual campaigning against the violence and injustice Sudanese women face. The picture quickly became one of the most shared in Sudanese social media, and it caused the relationship with my family to freeze for six months. There’s a lot to put up with, but I see the impact of what I do or say when people find inspiration and strength in it.’

It’s super interesting that you’re really good with writing and you’re super confident in the way you talk about it on the message boards, but then you say you have lower confidence in writing when it comes to your own work. It appears you need something to push against?

‘Yeah, I never saw myself as good at writing in general. But when I must, I do.’

How do you distinguish between the activism, the artwork, and the material of the artwork? I ask because activism is itself a form of material – that’s how I see it – or it’s the energy behind the work. There are all these things that extend beyond physical material.

‘I think they’re inseparable. They’re just different ways of working towards the same goal: a better and dignified life for my community.’

So, when you’re making something, you already have the issue in mind?

‘Yes. I start with a completely worked-out idea of what I’m going to do and what I want to talk about. And then follows the choice of materials and the question of how best to communicate the idea.

Early in March 2020, Sudanese social media was flooded with scenes of a horrific crime that took place in Abu Hamad, in North Sudan. A group of men were attacked by a mob of villagers after it was rumoured that they were gay. The victims were battered, stepped on and stoned. Two lost their lives, and one was in critical care in hospital. Over ten cafés belonging to gay men in the village were vandalised and burnt. The graveyard there was guarded by a mob who blocked the burials. The Sudanese government turned a blind eye to the incident. The official media said nothing about it either. “Human rights activists” have also, for the most part, played dead and kept their mouths shut. The humiliation and the death of these men was celebrated on Facebook and laughed at. I get daily threats that I will face the same fate as these men. I demonstrated during the opening ceremony of The Biennial of Sydney at the Museum of Contemporary Art, in front of my piece What Lasts! (Sarcophagus), which was part of the biennale. I made this piece about four years ago, after being told that I should have died before coming out as gay. This is still relevant to my case and that of my community. I held a sign reading “Sudan executes gay people under its government endorsement”.

I’m working on a documentary photo series about the Sudanese revolutionary women. The series will portray women who participated in the revolution, or who are living a revolutionary life. Sudanese women have been at the forefront of every political and social change inside or outside Sudan’s borders. This was also the case during the December 2018 revolution that led to the downfall of the 30-year dictatorship. Sadly, women are quite unfairly represented in the new government.

Another agenda behind this project is to build a new visual archive, free from the influences of the so-called “Islamic Renaissance” of the Al-Bashir era. Just Sudanese-ness in its purest traditional form. No shame, but pride in our heritage. Accompanying the photographs are interviews with those who are portrayed, and the photos and interviews will be published together in my social media. I don’t have a timeline for the project, and I plan to photograph as long as I can. In every picture I will include a bartal, a beautifully-designed food-tray-cover crafted by women in West Sudan, Darfur.’