Jorunn Veiteberg

Since its inception, Norwegian Crafts has concerned itself with developing new thinking about craft. In this essay by art historian and former Norwegian Crafts chairwoman Jorunn Veiteberg we are offered a closer look into Norwegian Crafts’ focus on theory development and craft writings, as she discusses challenges within the craft field today. Her unsurprising conclusion is that the concept of craft is neither unambiguous nor simple.

“Craft is a contested concept,” writes Tanya Harrod in the introduction to her 2018 book Craft. It’s a claim that many will agree with, which is one of the reasons why Norwegian Crafts has focused so heavily on publications, both print and online, and seminars, to promote a deeper understanding of craft both as a concept and as a distinct artistic field. When Norwegian Crafts first launched as a project in 2010, the timing was perfect.1 Developments in the education of craft artists together with the forms of practice unique to this category of art had heightened the need for new theory and debate about the distinguishing values and qualities of crafts.

The so-called Bologna Process is important in this context. In 1999, education ministers from twenty-nine countries signed a declaration at the University of Bologna, in which they agreed to work for common standards in higher education. One of the goals was to achieve greater mobility between European educational institutions, in part by introducing bachelor’s, master’s, and PhD degrees also in arts education. In Norway, this system was implemented in 2003–04, where it has led to a more systematic approach to artistic research and a stronger emphasis on theory. Today, art education is far more interdisciplinary in its orientation and many of the old distinctions between art genres have been dismantled. As a consequence, the umbrella term “crafts” has largely been usurped by the alternatives art or design. For the organisations and institutions that serve the crafts sector, this represents a challenge that demands new answers to the question: why identify as a craftsperson? Through its interviews with and portraits of artists with very different expressive idioms and forms of practice, Norwegian Crafts has demonstrated both its own relevance as an organisation and the relevance of the profiled artists to the crafts field. Its texts illustrate that a subject area and the theory relating to it are not fixed once and for all, but are constantly being challenged by what artists actually do.

There are still people around who view a dedication to materials such as clay, metal, glass, wood, or textiles as the antithesis of intellectual work. For them, it is inconceivable that one can think through a material just as readily as one can write about or conduct research into it. From the very outset, one of the goals of Norwegian Crafts has therefore been to help build the theory around what thinking through a material entails.

At the same time, it must be stressed that theory was hardly in short supply either in art education or certain parts of the contemporary art world at the time when the Bologna process was implemented. In fact, in Scandinavia, theory had been actively employed since the early 1990s as a tool in the struggle to determine what should be considered relevant contemporary art. Since contemporary art had “stabilised as social criticism” there was no longer any need for “tedious years of technical training”, as the Swedish artist Lars Vilks put it. Around the turn of the millennium, Vilks was professor of art theory at the Bergen Academy of Art and Design, prior to which he had taught at the Norwegian Academy of Fine Art in Oslo.2 In 2004, Vilks co-authored the book with the provocative title Hur man blir samtidskonstnär på tre dagar (How to Become a Contemporary Artist in Three Days). What was needed, he claimed, was training in how to think critically about the art institution and in how to refine networking skills. As it said on the cover: “In the past, it took a long time to become an artist. A long technical training was needed before anyone could create Art with a capital A. Today, things are much easier. […] For what matters is not the art itself, but the art world; its behaviours and habits and its agents; these are the essentials. Artistic quality is synonymous with effective networking. Artistic techniques can be reduced to just one: the ready-made.”

There are still people around who view a dedication to materials such as clay, metal, glass, wood, or textiles as the antithesis of intellectual work. For them, it is inconceivable that one can think through a material just as readily as one can write about or conduct research into it. From the very outset, one of the goals of Norwegian Crafts has therefore been to help build the theory around what thinking through a material entails.

It goes without saying that the concepts of art and culture are always in flux. But since the advent of movements such as “the new ceramics” and “the new jewellery” – as they became known in the 1970s – the identity of crafts has been even more unstable and fluid than it already was. It was these developments which, in 2004, prompted some of my European colleagues and myself to found Think Tank: A European Initiative for the Applied Arts.3 As we wrote in our “manifesto”: “Historically the applied arts have suffered both from a lack of critical attention and from the absence of an international perspective.” This was a situation we wanted to change through our activities. The aim was not to establish new rigid definitions, but to highlight the diversity of forms of practice within the crafts sphere and to ask questions. In our daily lives, few of us had many contacts with like-minded theoreticians with backgrounds in contemporary crafts. In the years that followed, this group of ten writers was the force behind annual publications and touring exhibitions based on themes that could be captured in a single word: Languages (2005), Place(s)

(2006), Gift (2007), Skill (2008), Speed (2009), Currency

(2010), and Show (2011). Whereas the publications up to and including 2010 were small books, the final print production was more like a folded poster. We lacked the funds for anything else, and as so often with self-initiated and self-financed initiatives, energy within the group was also beginning to wane.

This sense that craft is defined by its inferior status is, I think, crucial for understanding the 19th and 20th century, but for the 21st century, it’s misleading

While this is not the place for a history of Think Tank, I am nevertheless convinced that the group’s activities were an important part of the backdrop for Norwegian Crafts. It could be argued that, in launching its book series Documents of Contemporary Crafts,4 Norwegian Crafts picked up where Think Tank had left off a year before. We had also established a network that Norwegian Crafts could build on. Either way, I see a direct connection in the fact that André Gali, the editor of Norwegian Crafts Magazine, chose to interview former Think Tank member Glenn Adamson, an interview that is included in the current issue of The Vessel. Gali asks Glenn Adamson whether he believes crafts are still “fine art’s underdog”. The discussion about the relationship between fine art and crafts has often dominated the history of the latter. This is true both of Glenn Adamson’s book Thinking Through Craft, which came out in 2007, and in the aforementioned book Craft by Tanya Harrod, another former member of Think Tank. Harrod’s book includes several contributions by visual artists who write about their choice of materials or about crafts, as well as texts about visual artists whose practices are relevant from a crafts perspective. Notable examples of such artists include Lucio Fontana, Donald Judd, Phyllida Barlow, Bridget Riley, El Anatsui, and Martin Puryear, to name just a few. It is therefore hardly surprising that in her introduction Harrod touches on the art-crafts debate, and she does not mince her words when she claims: “No border has been more rigorously policed – by fine art curators and dealers and, occasionally, by artists themselves.” For someone like myself, who has been active in the crafts field since the 1980s, this seems a fairly obvious point. Numerous times I have encountered the argument that crafts are to be considered a minor rather than a major art and as such have no place in art galleries and museums of contemporary art. The authority of the 18th-century philosopher Immanuel Kant is often appealed to in defence of this subordination of crafts to fine arts. It is therefore interesting to note that this debate has commanded little space in the pages of Norwegian Crafts’ Magazine. It would appear that, for Norwegian Crafts, with its focal interest on the contemporary, this opposition is simply no longer valid. It is a view Glenn Adamson also seems to have arrived at over the years, to judge by the interview with André Gali: “This sense that craft is defined by its inferior status is, I think, crucial for understanding the 19th and 20th century, but for the 21st century, it’s misleading.” Instead, contemporary crafts have led him to conclude: “What I think we are living through now is a great convergence of these things into one undifferentiated field.” It is this more open field without strict boundaries that Norwegian Crafts has evidently been tempted to manoeuvre in, or rather, which it has been – and is – helping to create.

In the past decade, contemporary art has opened up to embrace many other aspects of visual and material art and culture. Textiles and ceramics in particular have become increasingly “mainstream” as both materials and media. The situation differs somewhat from one country to another, and in most places one still finds institutions and people who try to act as gatekeepers. That said, gatekeepers are not entirely absent from the crafts sector either. In Norway, from its inception in 1975 through to the turn of the millennium, the Norwegian Association for Arts and Crafts defined itself in opposition to both designers and traditional handicrafts / folk art. While there were good reasons for this, it is interesting to note that here as well the boundaries have since become rather porous. To my mind, Norwegian Crafts has been instrumental to this change. Since 2013, the Norwegian Association for Arts and Crafts has welcomed designers as members, and now it seems the time has come at last to open up more actively to craft-based forms of expression of Indigenous and national minority groups. In Norway, the Sami have the status of an Indigenous people, while the Romani and Roma peoples, Jews, Kvens and Forest Finns are considered national minorities.

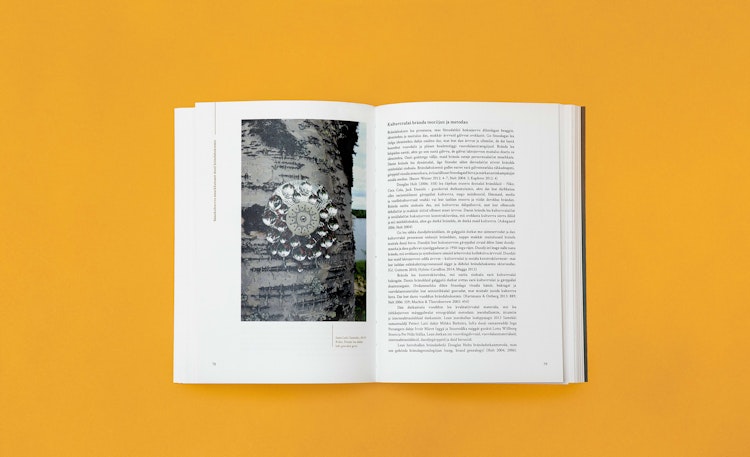

For far too long, the Norwegian arts sector, including the crafts community, has suffered from “colonial ignorance”, as the cultural historian Wayne Modest calls it when issues of colonial history are toned down in favour of comfortable national narratives. In Norway as in many other countries, Indigenous art is more commonly found in museums of cultural history rather than in art museums. The artefacts of these cultural groups tend to be considered more interesting when viewed from an ethnographic rather than an aesthetic angle. By linking up with guest theorists, curators, and artists such as Joar Nango from Sápmi, Namita Gupta Wiggers from the USA, and Zoe Black from Aotearoa New Zealand, Norwegian Crafts has striven to become more aware of its own blind spots and to establish an Indigenous perspective in its work. This means opening up to craft and art practices rooted in ways of thinking and values that differ from those of the studio craft movement and the Western fine art tradition. One of the fruits of this effort is a collection of articles published in both Sami and English under the title Duodji Reader (2022), a book that forms the basis for several of the artist presentations in the current issue of The Vessel.5

Spreading knowledge about Indigenous making practices effectively clears a path for an extended craft making concept. This may well imply new challenges for the crafts field, one of which concerns the relationship between tradition and innovation. Elements of tradition, whether of idiom, object repertoire, or ornamentation, have always had a valid place in crafts, albeit only on the level of reference, and not as a perpetuation of tradition for tradition’s sake. Where the divide runs between the two is of course debatable and also has to do with the author’s intention in any particular work. But by opening up the sphere of craft practices to reflect cultural backgrounds and purposes that are not rooted exclusively in the studio crafts movement, Norwegian Crafts also raises questions such as: does the practising of a craft amount to a profession, cultural heritage, or art? Or is it the case that we should simply stop thinking in terms of such categories and oppositions? Instead, we can exercise our ability to embrace the complexity of contemporary craft practices and the many different meanings they can carry. As work, a form of activity, craft figures in a vast range of contexts in today’s world – in factories and creative industries, in domestic pursuits, in workshops and artists studios, in rural and urban areas, in political and performative strategies (craftivism) – and is practiced by both professionals and amateurs. Especially those who work in a transnational arena, like Norwegian Crafts, are obliged to face the fact that the concept of craft is neither unambiguous nor simple.

Glenn Adamson has suggested that we should employ the term “craft” as a verb rather than a noun. In other words, we should focus on craft as a way of doing and not as a fixed object. I would agree that there is much to be gained from this shift in perspective. Certainly, the production aspect of making art deserves to be fetched into the light. Tanya Harrod’s book Craft is published in a series called Documents of Contemporary Art (the parallel to Norwegian Crafts’ series Documents of Contemporary Craft is hardly coincidental). Since 2006, the Whitechapel Gallery and MIT Press have added more than forty books to this series, each with a theme defined by a single word. The titles of the two that came immediately before Craft were Work and Practice. Is this indicative of a new contemporary interest in the material and manual aspects of art production? What is work and what does it mean in a crafts context? What kind of making practices are involved? Perhaps these two words, work and practice, suggest an area to explore when seeking to strengthen the identity of crafts in the future? At the very least, they may well provide a supplement to the focus on materials that has dominated the field in the past. One could focus on the question of the kind of work invested in any particular work, and by whom. Or on the kind of knowledge the work represents. And most importantly, there is the ever-more urgent issue of work ethics and sustainable means of production that demonstrate concern for nature and the environment. Here, craftspeople are well placed. Their extensive knowledge of both materials and methods is something worth sharing. It is a knowledge that represents values worthy of further reflection. Perhaps in the form of new artist portraits in later editions of The Vessel?