Sofia M. Ciel

In this essay, Sofia M. Ciel examines the work of Karen Kviltu Lidal, which explores society, architecture, and public life from the starting point of the physical body. Kviltu Lidal moves freely between art forms such as weaving, installation, and video documentation, but textiles prevail as her basic point of reference in both the metaphorical and literal sense.

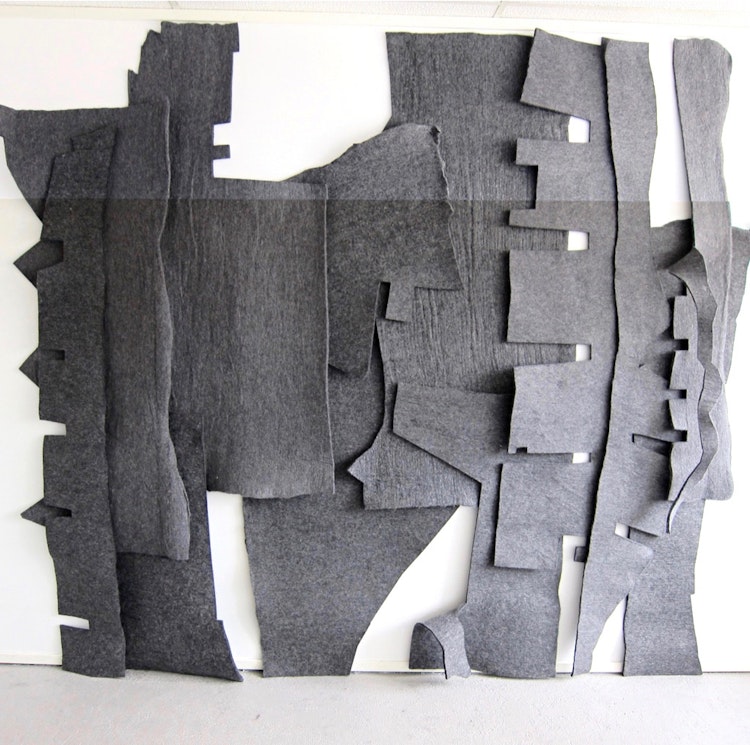

The plan of the city looks pretty odd; greyish pieces of thick wool felt, cut precisely in the shapes of streets, parks and buildings, are pinned on the wall in a way that makes them fall freely and completely dissolves the sense of a map (Possible City, 2017–2019 and Body/City, 2015, 2016). What’s the point of a map that makes orientation in space impossible? Let’s move then, for a while, to the thirteenth arrondissement of Paris and take into consideration Michel Houellebecq’s suggestion that “the map is more interesting than the territory”.1 But if so, where is this fascinating maze of scenic roads, viewpoints, forests, lakes and hills? Where are the green, red or yellow tones that mark the Earth’s different qualities? There are none. And there won’t be. However, city maps usually indicate this crucial starting point by saying: You are here. Where are we then?

Measuring public space with textiles

In her artistic practice, Karen Kviltu Lidal explores effects of the organisation of space; the way it impacts participation in social settings of public life, and relationships between elements such as the individual, the society and architecture. These issues she researches from the perspective of the body, in a way that makes her works visually remarkable and challenging. Viewers – in order to interpret the given setting – need either to be moving or imagining that they are moving. Lidal’s works are not really objects, but rather unfinished entities open to engaging in processes and performative gestures. She moves freely between art forms such as weaving, installation and video documentation, but textiles prevail as her basic point of reference in both the metaphorical and literal sense. This means textiles remain crucial, especially in relation to public space. Exploring and measuring a city with a piece of fabric, which is soft, means the fabric can bend and take on irregular shapes that enable different possibilities and outcomes. This is much different than measuring space with a conventional ruler that simplifies everything into straight lines. And Lidal loves to measure and examine borders.

‘I move, measure, draw, build and layout carpets to make a limitation, an occupied space, scaled to the body. [...] The projects can be seen as experiments on democracy, autonomy and self-sufficiency.’2

Her experiments with borders and limitations vary in scale. An early example is the installation Kappeland (2007). Produced in collaboration with the artist Runa Carlsen, this work extended across the whole of the city square Youngstorget in Oslo. What is important to mention here is that this square in central Oslo combines the eclectic aesthetics of the surrounding buildings that are from different periods and reflect different styles. The square itself has many functions: it is a place for street markets, street food vendors, political demonstrations and a range of other events. To create the work, Lidal collected textiles from various places and turned them into a huge carpet covering the entire city square. In an intriguing way, Kappeland – the name is derived from a children’s game that has the objective of taking control of as much land as possible – combined the private sphere (personal clothing) with the public sphere (the square). Textiles usually used on the body – either because of cultural norms or as protection – covered public area, as if inquiring into issues of protection and norms relating to public space. In this early work, one can already notice Lidal’s thinking about public space as a place for meeting.

This idea is followed up and expressed more demonstratively in her later projects. One such is Building (2008) – a temporary, performative sculpture in the shape of a wooden deck with a fireplace, created “to gather around for conversation, cooking and relaxing” outside a gallery in Oslo city centre. Another is Verksted (2008), also produced in collaboration with Runa Carlsen. This was a temporary space for exchanging practical skills and sharing knowledge. These works introduce a subtle critique of the capitalist order that usually links human presence in the city with the exchange of money for goods or services.

Lidal’s critique of public space doesn’t stop here but moves on to gender issues. From a historical perspective, cities were mostly shaped by male architects whose everyday duties did not relate to domestic labour. While planning public spaces, they were therefore never really compelled to think about the everyday logistics of domestic practices. Their plans stem from a privileged position that allowed them to move freely between the private and the public sphere, without any resistance or obstacles. For women, by contrast, public space, especially when they are present in it, has always been a realm for experiencing relations of power on various levels. This awareness comes from the simple fact of being excluded from certain places and from being criticised for the way they look, dress, behave and so on. This awareness comes from the simple fact of being excluded from certain places and from being criticised for the way they look, dress, behave and so on.

Lidal’s feminist approach seems especially visible in Her Constructions (2010), an installation based on the ‘Frankfurt kitchen’ designed by Margrethe Schütte-Lehotsky (1928). This female German designer made a kitchen that was intended as a place to meet and talk but also be functional and practical in its design. In this way, Schütte-Lehotsky actually created free time for women, so they could spend it doing things other than domestic chores. In this sense, Lidal’s emphasis on creating a space for just being and free time brings about an alternative to the capitalist order and modernist rationale. ‘Modernist’ here should be understood in a sense that is loosely based on the Kantian premise of neutrality (disinterestedness), aiming at stability and single-minded, focused thinking. What this scheme ignores, however, is its own lack of neutrality, as it suppresses such things as social conditions, personal bias, and bodily relations.

Karen Kviltu Lidal criticises modernist architecture in particular; her play with names of significant figures comes to expression in different works. In Le Corbusier’s Measuring Tape (2012)3, Lidal performs the action of measuring buildings with a colourful piece of woven woollen tape, thus ironically referring to le Corbusier’s anthropometric scale of proportions that was based on the height of a man with his arm raised. This particular scale was implemented in a few of Corbusier’s buildings, and Lidal pays attention to what she perceives as an idea of universality that is in fact not universal (for all) but discriminates against a large part of the human population. This line of criticism is followed up in Closed Open (Striated) (2019) and Closed Open (Plane) (2018), in which Lidal weaves with linen in doorframes typically associated with a modernist standard – again based on a man’s height and body. As she explains, “the modernist use of standards in architecture or design usually excludes something or someone”. Modernist exclusion – or alienation, to put it in other words – refers as much to architecture as to artistic practice and art criticism, as Amelia Jones notes:

‘Paradoxically, modernist criticism and art history rely on the (male) body of the artist to confirm their claims of transcendent meaning – with the critic or historian acting as “priest” transmitting this transcendence (as read through the art work back to the divine [invisible] body of the artist) – and yet insist on the occlusion of the body.’4

In this particular passage, Jones refers to the moment in art history when the body became visible in the process of creating. This was when Jackson Pollock initiated his performative painting processes, sometimes perceived as the vanguard of performance art. I draw attention to Jones’s interpretation of performance art to make a point: namely, that Lidal is performing the textile rather than creating objects; her practice escapes simple categorisations and changes the focus from things to gestures and relations. How can one deal with the reality that remains in a contestant state of flux? It must be analysed and measured frequently, again and again. And Lidal’s textile performances usually involve measuring.

Forced and voluntary nomadism

In Kyriakon, Relocated Holy Space (2012), Lidal recreates the Sub Church meeting hall floor plan (the building is located at Kirkegata 34 in Oslo and previously housed night clubs) in 1:1 scale in a green field. This gesture of relocating the building to the open space allows us to notice its contours that are invisible in the urban setting. While in the performance-video This Is All We Need (2009), the artist marks on the ground a square of three meters in several locations in Oslo. Exactly that much space – according to philosophical and architectural measurements5 – is enough for an individual to create a home. Three meters does not seem like much, but placing that kind of square in the city space inevitably raises a question: Who owns it and who can afford it? Perhaps not that many, and economically unprivileged inhabitants often move out due to expired leases or rising rental prices, which force them to move further away from the city centre and to live in constant unpredictability. This makes it hard to feel at home. This mode of fluid existence is something artists can relate to. As Lidal says, in the sketch for Studio Geography (working title) (2019):

‘We move to the spaces we can afford to work in. We are always on the go, packing up our tools and materials, moving around the city, but also around the world to different residencies. There is freedom in this, but also great frustration. How can one find room for production in an overly commercial and gentrified city?’

Forced nomadism has nothing to do with the voluntary kind: an individual’s decision to move freely from one place to another. Lidal creates a metaphorical and poetic juxtaposition between the two, to make ground for her philosophy of maps.

Maps of attachment

In the already-mentioned works Possible City and Body/City, Lidal uses felt made by Mongolian nomads. For them, a home is always a provisional and temporary structure in an endless process of moving from one place to another.6 In the frame of nomadic existence, the map has a different function and meaning then in a stable place that usually involves different sets of practices. Furthermore, traces left by nomads and non-nomads carry different relations to materiality. As perhaps Deleuze and Guattari would comment on the nomadic life, the map has to do with performance, whereas the trace always involves an alleged competence. The map remains a more open and connectable structure in all its dimensions, as it is detachable, reversible and susceptible to constant modification. It can be torn, reversed, adapted to any kind of mounting, and reworked by an individual, group or social formation. It can be drawn on a wall, conceived as a work of art, constructed as a political action or as a form of mediation.7 Of course, this specific understanding of a map has little in common with its traditional form, which pictures a certain concept of space that is political, social, cultural, visual and imaginary. Traditional maps are not transparent, nor are they innocent documents; the forms they take reveal not only specific data but also a given discourse on how space is understood. Maps do not show objective knowledge or truth, but are an effect of producing and reproducing visions of power. Looking at maps from a scientific point of view, even significant geographers like David Harvey or Edward Soja considered them as a document that privileged space over the body; the reverse thinking, which analyses space in the relation to the corporal perspective, has never really been developed. In reality, the body – understood as a physical, emotional and political entity that is a place for such markers as race, gender and sexuality – has an enormous effect on how one experiences space. With this thought, I return to Lidal’s peculiar maps and plans of cities and to the starting point: You are here. Where are we then?

Lidal’s maps cause us to puzzle. Apart from pieces of greyish textile left freely hanging on the wall and dissolving the orientation in space (Possible City and Body/City), there is another map: the monochromatic surface made with pastel on paper – a concentration of points. Thirty drawings hung on the wall form the large horizontal piece Home (Emotional Geography), (2019), which shows a river running through a Norwegian valley. But this is just one of many options, for the drawings can be combined into a variety of constellations and compositions to make completely different maps. The subtle depth of Home comes from a specific texture obtained through the frottage technique; the basis for the work was an uneven wallpaper with pieces of wooden fibre called Rauhfasertapete.

All of Lidal’s maps have a personal connection to the past. It is as if the folds, cuts and points are picturing different forms and tones of emotional attachment to a place, as if the process of creating a map is like moving from something strange to something familiar. Everyone knows this feeling; the river known from memories and shown on a map evokes different associations than does a blue line in an unknown space. While the former brings to mind pictures and emotions memorised through and in the body, the later remains little more than a geometric figure.

The dissolved shapes and monochromatic surfaces of Lidal’s maps remind us more of cartograms than conventional maps that are used to substitute certain data or thematic variables for land areas or distances, and as an effect that distorts geometry or space. In cartograms, the deformation serves as a tool to highlight a specific element. What then is Lidal trying to highlight? It seems certain that her maps can be images of different tones of emotions and personal memories, but they also carry a more general thought; traditionally understood systems of orientation were based on excluding norms and wrong presuppositions. What can one do to become more attentive to, and perceptive of, external space? To perceive – to recall Maurice Merleau-Ponty – is to render oneself present to something through the body; the things have a place within the horizon of the world. Our way of interpreting and understanding external reality consists of putting each detail in the perceptual horizon to which we belong.8 Lidal’s answer to the question Where are we? would then be very simple: In the body.