Kristin Valla

British artist Grayson Perry is a television star and transvestite whose best friend is a teddy bear. But he believes that making ceramic vases is far more provocative.

‘Sexual transgression is almost expected of you in the artworld. Craft, however, was terribly unmodern when I finished school. In fact, I remember one of my teachers saying craft was dead. At the time painting was becoming popular again, with Baselitz, Schnabel and Kiefer, all these macho-painters. I liked making small, fragile things by hand. In the first half of my career I felt I was swimming against the current. At the same time, I like the fact that the things I made caused people to feel uncomfortable.’

Grayson Perry has sat down on a sofa in the basement of ARoS Art Museum in Århus, Denmark. It is here that the exhibition Hold Your Beliefs Lightly – his first show in Denmark – opens in a few days’ time. Earlier in the day he gave a tour of the exhibition to members of the press, couching his works in a good dose of humour. He’s wearing his “male uniform” today: blue chinos, jogging shoes, a T-shirt and a lumberjack shirt. Last night he drank Champaign underneath Olafur Eliasson’s rainbow-diorama in the guise of his alter-ego Claire, wearing a dress that brought to mind a priest’s cassock. Grayson Perry was in his early teens when he first began wearing women’s clothing.

‘When you, at 12-year-old, get a strong yearning to walk down the main street of your hometown dressed as your own mother – that does something to you. My greatest fear was to be seen and noticed. I learned early on that it wasn’t so dangerous to be uncool. You won’t die from it. Being a transvestite, at least for me as an artist, has meant that I’m not concerned about being cool’, he says.

Evening class in ceramics

Paradoxically enough, Grayson Perry is one of the coolest people the British artworld has to offer. He’s one of the few craft artists in the world who gets stopped on the sidewalk and asked for his autograph and a photo. It is particularly the television series where he explores various aspects of social class and gender roles in British society that have catapulted him to being one of the UK’s favourite celebrities. But also the fact that the formats Perry favours as an artist are so very different. Vases. Tapestries. The sorts of things people have at home.

‘During the first half of my career I made almost only vases. Vases and plates. I learned ceramics in an evening class, and I wasn’t particularly good at it. I attended an art school, but I had no technical expertise. This vase here, for example, is a very early work’, he says, pointing.

‘It’s from 1986. I had started making ceramic objects three years before.’

We’re now standing in a gallery room at ARoS that is entirely devoted to vases. There has to be a room like this in each and every Grayson Perry exhibition, he explains, because this is the format he has worked with the most throughout his career.

‘But it’s difficult to get curators to ask for the vases to be included in exhibitions since they’re fragile and difficult to transport. Furthermore, the owners are usually very fond of them.’

He points to a more recently produced vase, made in 1992. At first glance it looks like a completely ordinary vase. On closer inspection, one sees “arsehole” written across a picture of a beautiful rose.

‘At this point I was starting to get really good’, says Perry.

Why did you become interested in ceramics?

‘Well, it was always seen as a second-rate medium to work with, and that’s probably also been much of the motivation for getting interested in themes like social class and taste. But maybe most of all because ceramic objects are primarily made by craftspersons rather than artists. Furthermore, ceramics is very feminine, which also causes it to be looked down upon in the field of art. That made it very exciting in my eyes. Everything the artworld looked down on was exciting! These are not ironic vases. These are proper vases. That bothered the artworld.’

When Perry won the Turner Prize in 2003, he said ‘it’s about time a transvestite potter won the Turner Prize’. But he’s keen to stress that he doesn’t actually see himself as a craftsperson.

‘I’m not interested in being innovative. I assume that’s something ceramists aim for. I’m an artist who happens to be working with ceramics. That’s something different.’

How is it different?

‘Just as most artists are not particularly good craftspersons, most craftspersons are not particularly good artists. The main problem for people who work with crafts is perhaps that they call themselves craftspersons. Art deals with ideas, while the crafts have very much to do with how things are made. If someone at a party asks me what I do for a living, I reply that I’m an artist. A ceramist would say he makes ceramics. That is very limiting.’

Nevertheless, you work a great deal with traditional craft formats such as vases and tapestries?

‘Yes, because then I don’t need to create a new aesthetic around this. It’s already there. Instead, I try to use this as a starting point for discussing modern themes. It also means people don’t need to struggle to understand what’s beautiful about these works. All that’s necessary is to think about why the works don’t resemble historical vases’, says Perry, and adds:

‘I think oftentimes people walk into a gallery and think: “What in the world is this?” The things I make, by contrast, are already well-known. The public enter and say: “That thing there is a vase”. So they can relax.’

Teddy bear as best friend

A leitmotif in Grayson Perry’s works is his teddy bear, Alan Measles. Perry’s parents gave it to him when he was young – so young that he can’t remember a time in life when Alan Measles wasn’t there. In the exhibition at ARoS the teddy bear can be seen in tapestries, sculptures, and atop a huge Louis Vuitton suitcase. Almost like a divine, mythic being.

‘My teddy bear was a very important and large part of my childhood’, he says.

‘My family was really dysfunctional, and I created a very organised imaginary world built around Alan Measles. All my playtime was devoted to him and the world I created for him. I think it’s quite a common way for children to comfort themselves and to try to create a kind of order in all the chaos.’

Grayson Perry’s father left the family when his son was four years old. After a while another man moved in and became Perry’s step-father. But Perry had a problematic relationship with him. For Perry, the step-father represented one type of masculinity, the teddy bear another.

‘We all have a mental image about what it means to be something, for example to be a man. Oftentimes the challenges in life are about how we live up to that image. For me, Alan Measles represented a perfect, positive, masculine role model. Back then I was engaged in a constant war with my parents, and in my imaginary world Alan Measles was always fighting the Germans, who of course stood metaphorically for my step-father.’

In 2011 Perry curated the exhibition The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman at the British Museum, where he juxtaposed his own works with selected objects from the museum’s own collection. The exhibition was a celebration of handicraft, since many of the objects Perry selected were made by anonymous people. In connection with the exhibition, he went on a “pilgrimage” throughout Europe on his specially-made Kenilworth AM1-motorcycle, with Alan Measles sitting behind him. The motorcycle is now on show in a separate room at ARoS, along with Perry’s motorcycling togs. At the front of the machine is a silver cast of Alan Measles, like a galleon figure. At the back sits the teddy bear himself, in a specially-made little house.

‘And between all this is a large amount of therapy’, says Perry, measuring the size of the therapy like other people demonstrate the size of a fish.

‘But this isn’t the real Alan Measles sitting at the back here’, he quickly adds.

‘It’s his stuntman. Alan doesn’t like to travel, and in any case, he doesn’t like sitting in a museum for an extended period. People are always sending me teddy bears that can be stand-ins for him.’

When one of the British Museum’s directors asked Perry why he wouldn’t include the real teddy bear in the exhibition, it was revealed that Perry doesn’t trust anyone when it comes to his most beloved bear. Not even one of the world’s most burglar-proof museums.

‘When I was little, I was always Alan Measles’ bodyguard. That’s how important he was for me’, Perry explains.

Where do you have him now?

‘He sits on a throne on the desk in my studio.’

And what kind of shape is he in?

‘Pretty poor. He’s a 50-year-old teddy bear. So you can imagine.’

Weaving on a computer

Alan Measles and Grayson Perry still hang out alone together in Perry’s studio – a former shop on the outskirts of east London. Even though one of Perry’s vases can now sell for around one million Norwegian kroner at auction, he has no large apparatus of assistants.

‘I would love to have lots of people around me; the problem is, I wouldn’t know what to ask them to do. I use assistants when I, for example, weave a tapestry or build a house. Then I get craftspeople to help me with the production. But when it comes to drawing and creating sculptures, choosing colours and expressions, I need complete control over every tiny detail.’

You do all this alone in the studio?

‘Yes. Or, actually, I have a friend who rents space in my studio, so sometimes I ask him to help me lift things. Some of the pots are very heavy.’

Perry once again stresses that he’s not a typical ceramist. In contrast to normal procedure, he applies slip glaze before biscuit-firing.

‘Of course this poses a great risk because the kiln is a temperamental tool. It can really kick you in the teeth. As such, clay is one of the most unforgiving media to work with. I can work on a pot for a month, and then it cracks in the kiln. But after doing this for 35 years, luckily I’ve gotten a bit better at it. Nevertheless, I’m still scared every time I open the kiln. Some ceramists call these accidents “the gift of fire”. For me, it’s like the socks you got from your aunt for Christmas. You don’t really want the gift’, he says.

Has technology changed the way you work?

‘Yes, enormously. The tapestries, for example. I create them on a computer-steered loom, so I can design even the largest works in just a day. I use a digital drawing board, which was a real revelation for me. It’s difficult, in practice, to draw something 15 metres long. It’s actually a nightmare. But on a computer you can enlarge a small portion of it, or you can reduce it to a postage stamp. It’s brilliant. You can change things all the time. If you make a mistake, you push a button and it’s gone.’

The invasion of brands

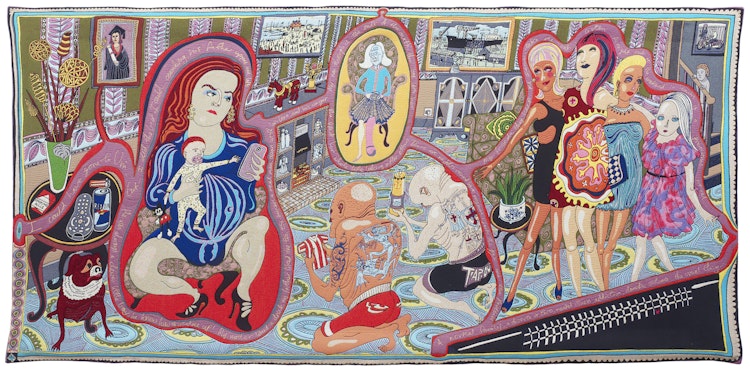

In one room at ARoS, we find Grayson Perry’s largest work to date: The Walthamstow Tapestry. It’s inspired by the famous Bayeux Tapestry (1070s), which is themed on William the Conqueror’s invasion of England. Perry’s tapestry is 15 metres long and woven on an electronic loom in Ghent, Belgium. Also here, invasion is the theme, but in a different way.

‘While the Bayeux Tapestry is about the Norman invasion of England, this work is about the invasion of brands into our minds. Each word in this tapestry represents a brand. I think of one of those logo boards you stand in front of to be photographed before you walk into an event.’

The tapestry was made in connection with a book launch held at a venue with a “very large wall”. Perry thought it would be just as well to cover the wall. Since then he has created several more tapestries, none however, as large as this.

‘One of my favourite quotes is that you’ll never have a successful art career unless your work fits into the elevator of a New York apartment block. The first time I saw this work in a home was when I visited the architect Norman Foster. His wife bought the first rendition of the tapestry and invited me to see it in their house outside Geneva. It was hanging in the garage!”

Grayson Perry laughs.

‘Not even Norman Foster, the architect behind some of the world’s largest buildings, had a wall in his house large enough for this tapestry.’

He raises his hands in exasperation.

‘I’ve never made anything as large as this since then.’

I learned early on that it’s not dangerous to be uncool. You won’t actually die from it.

Grayson Perry on…

…dressing as a woman

‘In general, I can say that I dress up when other people do. And it’s usually in women’s clothing. There are design students at Central Saint Martins in London who create my wardrobe, and every year I have a big shopping day: I buy clothes from the students for around half a million [Norwegian] kroner. They are very creative, the students. Not everyone is as good at sewing, and some of the outfits fall apart while I’m wearing them, but I love how inventive they are.’

…about religion

‘The first time I did an exhibition themed on religion I thought: What can I use as my god? And then it struck me: My teddy bear, of course. He was a big and important part of my childhood. People love their god because they’ve grown up with him as part of their culture. I grew up with my teddy bear, so I now use Alan Measles as an image of god in the exhibition.’

…about humour

‘The British are very afraid of big feelings, and humour is a means for protecting ourselves from them. If you talk about something serious, using humour can make it easier for people to open up to it. There’s an adage: There’s no common sense without a sense of humour. Just look at dictators. Very seldom do they have a sense of humour. Humour shows that you’re flexible, that you’re willing to see things from other perspectives and to make changes. I think humour is the lubricant in British society.’

…about being popular

‘Being popular has been negative for artists for a very long time. I think there’s still a negative charge in it, and that some artists think being popular is problematic. But they still want the prices of their works to increase, don’t they? And how do they achieve that? By getting recognition? And how does that come about? By exhibiting in museums and galleries? And how do you get your works into museums and galleries? By being popular, so that people come and see your art.’