matt lambert

matt lambert and Máret Ánne Sara

In this text we get to follow matt lambert and Máret Ánne Sara's conversation, as they explore their shared experiences, their impetuses for creating art, and the role migration, nomadism and land play in their practices.

On 7 March 2018 I participated in Saying NO NO to Kantian Autonomy and Getting Jiggy with New Materialism, a daylong seminar arranged by Norwegian Crafts as part of a series run by Current Obsession during Munich Jewelry Week.1 The seminar touched upon practices that avoid or challenge the Western notion of art. Máret Ánne Sara was also contributing to the seminar and it is there that Máret Ánne Sara and I first met, and although I was not presenting on my own studio work, and there was not much time to speak to each other, there was still enough time to sense a commonality in having a strong conviction to our practices and how they engage with larger humanitarian issues.

Máret Ánne Sara is a Sámi artist and author based in Guovdageaidnu.2 Her project Pile o’Sápmi which was presented at Documenta 14 initiates a conversation around Indigenous rights and present-day colonialism. In short Pile ó Sápmi started out as a reaction to government forced slaughter of the Sámi people’s reindeer in Finnmark, in Northern Norway. Sara’s brother Jovsset Ante Sara went to court to fight the Norwegian government and Sara engaged in this process through artistic expressions. Pile o’Sápmi can be considered both as an artwork and as an artistic movement and was first presented as a mountain of freshly slaughtered reindeer heads crowned by a Norwegian flag at its peak and installed in front of the Indre Finnmark District Court (Sápmi/Northern Norway) in February 2016. Since the project has branched out into a number of works and events that deals with Sámi rights and what Sara has described as a new colonialism, enforced through administrative and political structures and legislations from the Norwegian government. In Documenta 14 Pile o’Sápmi was shown as a curtain of 400 reindeer sculls, with subtle references to the Sámi flag. This work re-appeared outside the Norwegian parliament during her brother’s trial that in December 2017 reached the Supreme Court in Oslo. It was this work Sara presented in Munich as well as a jewellery piece that belongs to the same project. Through showing and talking about these works Sara was raising awareness about the current situation for the Indigenous people in Sápmi (the land of the Sámi people in Northern Norway, Sweden, Finland and parts of the Cola Peninsula in Russia) and how Indigenous people still are being colonized.

Most Norwegians are not even aware of their country's colonial history, the official assimilation of the Sámi’s or our present-day reality

Later Sara invited me to collaborate after seeing my own artistic practice which shares parallels to her own. My practice is based in Detroit and uses the vernacular of jewelry – a language I feel has the ability to disrupt Western institutional thinking about divisions of craft, art, fashion, performance and design. My current existence has become one of nomadism traveling to research, experience and work collaboratively giving up an address or physical home. While in residence with Praksis Oslo on Gender and Adornment supported by Norwegian Crafts I independently traveled to Guovdageaidnu where Sara and I further explored our common ground meeting as an Indigenous and queer body. Those experiences are some that are impossible to put in words and allowed for us to feel the ground we share. What follows is a edited conversation that initially occurred in an online video chat in August 2018, looking back at how we got here and how we are navigating our present.

I first want to ask why you approached me to collaborate?

‘I think your work is interesting, very bold and out of alignment with tradition. I think this also of your approach. Not only in results, but the way you think around work. Another reason was because jewelry is totally new for me. It was by coincidence that I made something that eventually was a piece of jewelry, or I don't know what to call it really... For me the meeting in Munich during Schmuck also piqued my curiosity. Especially through your work, I saw a strong and personal significance in how interaction with the objects changes once it's on your body, how you sort of read things when you wear it.’

I’m drawn to this as well... this making jewelry by accident or even the necessity for an object to engage with a body. I feel it’s important that these objects do begin to talk to bodies because ultimately the work talks or engages actual bodies and not just watching, you know, a culture or a group of people as just a conceptual idea. Sámi are real people, and it adds a moment of a humanization.

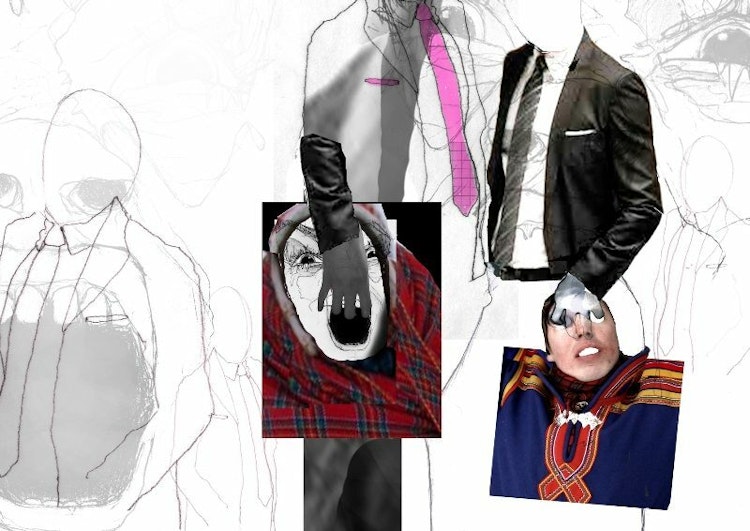

‘Yes, this is important in today's society, especially in the kinds of structural issues that Pile o’Sápmi and we now are addressing. For example, the collar we made together from the jaws of the reindeer heads shown in Documenta 14, Loaded keep hitting our Jaws, one sort of feels this weight also on the body and then this brutal material placed very elegantly and beautifully on a body, serving as a reminder of these real people, carrying a brutal and heavy burden, but this… this is not evident in structural politics. Therefore not discussed nor regarded. People dealing with difficulties or hardships rarely have capacity to politically address this situation, so the samarium is that nobody is concerned with the human sufferings of these huge political and legal issues that new colonialism in Sápmi is about.’

I find when speaking to people on concerns and issues of Sámi they kind of assume Sámi don't exist anymore, which is strange and unsettling. I think it’s crucial, projects like yours as well as other artists from Documenta 14 initiated a larger conversation around Indigeneity.

‘Yes, I think for me, there’s no real surprise because my starting point is from Norwegian society, where most Norwegians are not even aware of their country’s colonial history, the official assimilation of the Sámi’s or our present-day reality. Since our history has been structurally and effectively hidden, I don’t expect more from the outside world to be honest, but of course it is tremendously important and helpful for our situation, that people are informed outside of Norway.’

Is this where the idea to collaborate becomes crucial? These are situations where I'm angry and feel agency too, it should be heard, and it should be talked about. Sometimes it is very different having a perspective outside the direct conflict.

‘Yes, indeed. Collaborations are priceless for minorities, and I also think that it is important to connect our common fights on certain levels. While discussing one certain case, it is also important to make connections and evidences to similar cases and struggles amongst Indigenous people or other minorities in the world. I would say that my feelings are always a bit conflicted due to humbleness to all these harsh fights. Our issues are of course super urgent, but at the same time, there are so many urgent issues going on everywhere. We must be aware not to compete about the urgency around our common struggles, but rather connect them. It's very easy, refreshing, and right to work with you for instance. I wouldn't have this ease if I were collaborating with an artist whose understandings of the reality in Norway is totally different. You come with fresh sets of eyes and are not demanding me to compromise or evidence my reality and history due to a set public image of Norway and its fairness.’

The hardship of stepping out of our histories is a global colonial issue. We talk about nomadism and can touch on this idea as makers, creatives, and musicians. Anybody who travels like we do can begin connecting dots where you just see the effect of colonialism on our globe and how difficult it is for people as we see with your brother’s court case or with the Dakota Access Pipeline protests to protect Indigenous land in the US from pollution.3 It's hard to blame an average Norwegian for not knowing because how do you get it? out of the textbook? How do you change the canon presently since it’s been here for so long; are people all of a sudden going to believe oppression has occurred not even two hours away from their own home where they grew up?

‘Exactly. For me it is really about addressing the ongoing history of colonialism, show the reality and opening the eyes for the public to see how methods have changed by using the legal system, but the intentions remain. We need to be aware and question this idealized, fair democracy where colonialism nowadays is adopted and barely seen. By addressing this issue in a superiorly “fair” democracy such as Norway, one can expand to discussing the global impact everywhere.’

The connecting threads, that quality, is the power of this

project. Also, what you did before we worked together, and what I

believe is going to happen, is the project allows one to expose

something without forcing it, without engaging in an attack - you're not

force-feeding the public. We can present, as you said, in someone’s eye

shot, they can take it or leave it. But we are not shouting “this is

the thing, it’s big! We should talk about it.” However, the challenges

come with continuing the education. And this is where I’m at, working

collaboratively helps to relieve some work. Now I'm learning enough to

be comfortable, or at least give people proper information for them to

look at other things. And I hope this spawns other people to do the

same.

‘Hearing more than one voice is critical. I usually invite a lot

of artists to show relevant works alongside my own. Everyone has a

different artistic language, or language in general. So you get an

expansive range in arguments, perspectives and audience. For instance,

your language is totally different than mine, so is the concept of

jewelry, it is about finding other ways to talk through and show

different notes. Then, once the information is out there, you can

activate different groups in society. Let’s say the media, we have to

activate the media to talk about this, and we activate academics, then

maybe the legal societies - from this a line of thinking begins forming

in society. These are ways we can start some sort of change. Nothing can

change unless people begin to think, talk, and critically question

things more. But the essential base is information, or education I

guess, about certain realities such as ours.’

But up until now, you have collaborated with just Sámi artists?

‘No,

I recently collaborated with the Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña who was

also in Documenta 14. We made a collaborative piece for Pile o’Sápmi-Supreme

following the Norwegian supreme court trial. Cecilia uses the form of

the quipo to make these huge textile pieces with big knots.4

When I asked her about the piece in Documenta, she told me the knots of a

quipo were the first “written” language of her people. A way of

storing, communicating and passing information. This “language”,

disappeared when the massacre of her people occurred so, the language

died, along with her people, she said. Our collaborative work, the Gákte-Quipo

we made to connect the Indigenous struggles and voices from south to

north. I decided to make the piece from gáktis, the traditional Sámi

dresses. What I did was post a Facebook note one and a half weeks before

I went to Oslo to make the piece, asking people if they wanted to

donate their gákti for a new Pile o’Sápmi piece, with the

purpose of addressing my brother’s struggle against the Norwegian

government and the structural abuse of our rights and existence. When I

arrived in Oslo, several boxes had been sent there, containing gáktis

from different parts of Sápmi. These dresses are so personal because you

make them yourselves and you can trace your family and region by how

the ribbons and the colors are arranged. Then, just the fact that you

have been wearing them until they are worn out, then donated for this

piece where they are all tied together, in a Quipo. It's connecting

Sápmi, and our Indigenous voices on a spiritual level across the globe. I

think we need to be able to address the colonial history, both in a

very brutal perspective like Vicuñas Quipo, and then from the north of

Norway, where we have what you could call brutal ‘soft colonialism’

going on. We need to make these comparisons to see realities and

intentions for what they are and in relation to each other to be able to

change anything. We cannot talk about cases like they are separate. For

instance, the case of land issues, where governments and companies are

taking one piece at the time, only regarding this one singular piece of

forest or fjord. Discussing interventions separately and isolated is a

power strategy. By not zooming out to consciously regard the cumulative

effects for a whole region and ecosystem in relation to traditional and

natural livelihoods and people, authorities and companies can officially

minimize the impression of damage and thus minimize responsibility.’

Yes, macro versus micro. I'm super interested in nomadism, but I also wonder, when you get to macro level, what is nomadism? Because you're looking at such a big picture ... is the idea of space relevant anymore? Talking to people about the idea of being nomadic, from a colonial sense, implies time and space. What I've learned from working with you, and from working with other groups of people, is how we consider time and space. It needs to change as it all doesn’t move in one direction at the same speed. To get on that level, then, how far really is Chile from Norway? When you zoom out and you find those comparisons and those parallels, and you're talking about making these knots with garments. Garments: with things that are worn, which put the body back in, which, I would make the argument, has the potential for being called jewelry.. So, you may have been making jewelry before we were working together.

‘Could be.’

The power of that piece is its implied body, it humanizes and places a figure in front of people, but does not yell, “here is one person, here is another, this is their story,” it is more “here’s people.” It is the collective narrative, like you said, as opposed to the singular one.

‘When you asked, how far is Chile, for me, it's not far at all. I have also collaborated with artists from Guatemala, for instance. ... I'm always humbled, and I'm always sad because I know the brutal reality. When I'm talking about colonialism against Sámi, is it brutal? Yes, but not bloody as it still is for many Indigenous people. Indigenous peoples' histories have similarities. As do our wounds and worries. These places are not far at all. For me it's further, much further, to Oslo than to Indigenous Guatemala, Chile, Canada or Australia, because of shared or relatable experience.’

Curious. How important was it that I actually came to Kautokeino? I ask in reference to your surprise when I told you I was coming.

‘I'm not used to Western people being so nomadic in their way of thinking and acting. For me, it was great. Wow! Real meetings real exchange, real understandings.’

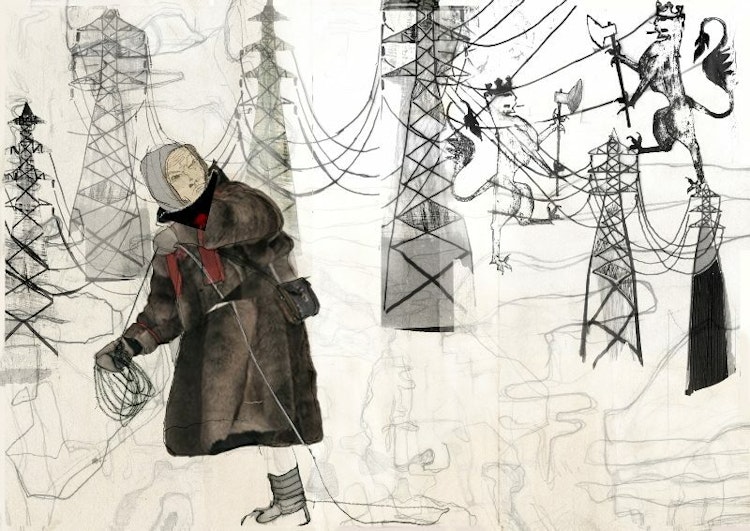

Máret Ánne Sara and matt lambert participated in the exhibition JOIN by Norwegian Presence in Milan 2019. Photos by Inger Marie Grini,

I also feel that queer perspective, so to say, is similar to an Indigenous one. It's not foreign at all to discuss these issues with you. I sense a similar understanding of colonialism, of being a minority, this constant fight for basic rights, and a fair position in society – This naturally connects us and places our making on the same line of thought.

I agree. I found it important to come simply as I am not an

Indigenous body and I wanted to enter your space to get a better

understanding of why you started the Pile o’Sápmi project.

You said before, there's implicit knowledge that exists between

Indigenous peoples. This I am only beginning to understand. When I wrote

to you saying, ‘I can’t do this unless I come’, I did so as it would be

very strange as a non-Indigenous North American maker to not come. Was I

going to make things in my studio without any context? The work as I

pictured it, before I visited, drastically changed because of my choice

to come.

‘I also feel that queer perspective, so to say, is

similar to an Indigenous one. It's not foreign at all to discuss these

issues with you. I sense a similar understanding of colonialism, of

being a minority, this constant fight for basic rights, and a fair

position in society – This naturally connects us and places our making

on the same line of thought.’

We definitely share a way of

seeing. The pieces we made first weren't planned, they were spontaneous.

Making without questioning is really nice. You showed me a lot, we

talked a lot, stayed up and talked for hours. We found our

commonalities, which for me is the best thing about making and being

nomadic, the conversations that I get are invaluable. The piece isn't

necessarily the work. It's the dialogue and the exchange. It opens up

and connects queerness and indigeneity, and how those languages do meet,

and what wounds do we share. Through work we talk about family,

heritage, and everything else in very different ways.

As a queer person, my lived traumatic experiences are handed down

through other queer bodies. But, it isn't necessarily through my

family. It's not through blood, whereas, indigeneity is partially

defined through bloodline, but seeing and being in Kautokeino, which I

admit was intimidating at first, made me realize there are several

commonalities.

Again, it's just the need to think differently, on

... how we consider what a family is, what a lineage, legacy, or

heritage is. I realize that sometimes I have to check myself … when I

think of my academic training I have to realize that it is still a

system to develop thinking, one that participated and often still does

in colonialism. I have to remind myself that there may be other

possibilities or narratives I am missing, I must stop myself to reflect

on this from time to time. I have to stop and think, ‘why do I think

this way? Who told me to think this way? ... I is there a different way

to look at this?’

I am drawn more to the way Indigenous people

look at almost anything…..material, about space, and time-here' is

openness without anxiety and the crushing fist of colonialism coming

down on it. That is what I get out of it, it’s why I travel the way I do

for those conversations. We could never have this conversation if I

didn't go there. I don't think we would have begun to make the work that

we are now [making] if I didn't actually come to Kautokeino and see

people.

‘Oh, no. Definitely.’

Like Sunday

morning. We went into the house and there was a group of older women in

head-to-toe traditional dress. You just take it as normal, and I'm

trying not to stare, but it's so impactful for me. For you it was just

another Sunday or any day. But, for me this is what I've looked at only

online and seen hung in museums. I saw some during National Day in

Norway, which was beautiful to see, but not like that. They were just

sitting down and having waffles for breakfast. In this way you realize

that people live differently, and that is normal. It's not a costume,

but somebody's clothes.

‘Going back to [the fact] that all

of these clothes are made. Every color is planned, according to your

family traditions. In my family, it's been a tradition to have a lot of

yellow in the combinations in these dresses. I'm glad that you noticed

them. For me, it's everyday stuff. But, not only, in this piece with

Cecilia Vicuña, for instance, I really feel the emphasized connection,

the personal and collective connection of these garments and their

history. I think this is the power of collaboration, that in

collaboration you compare and view everything in a much different and

also much more elaborated way. I think that's why it's so emotional,

because then you get to look and go, "Oh, wait, that was there the

entire time. I didn't even realize because it's just part of our

natural, everyday living." You also have to add that, for me, just the

way that I like to create, and just my own curiosity, I love the idea of

just handing over something like this porcelain heads to someone like

you, and just say, "Come on. Work your amazing, creative mind and go

crazy." It is about trust and allowing an open vulnerable dialogue.’

That's

even more crucial of why I had to be there. To understand, yes, I'm

going to treat these objects with reverence because they were in

Documenta, and that's a standard in what we know as the art world. But I

don't have the reverence for what they symbolize until I was there, to

realize what they symbolized, and how they should be treated, because, I

can carelessly set them or treat them as just precious stones. After

being there, I realize they have a voice, and they need to be able to

speak. The way we look at objects is as very art oriented, everything

around us is curated, which is a reason why I don't like jewelry at

times, we put it in a case or it’s made to be looked at and not actually

worn by a real person. We put it behind the vitrine. We make it very

precious but less sacred. To me, sacred or ritual objects are used every

day. They are touched and handled, - this is where preciousness comes

in. Just like your family and your community, you have them every day.

Something is precious through craft made objects, because we use it

every day. Putting it behind glass, to show it in an art object way

takes life away from it. It has to be done, I get it... Certain things

need to be preserved, and that's a whole different conversation, but, in

general, it taught me a lot of how I should handle these as a material.

To be there, to see how everything else is used.

‘I have to

say I liked your initial ideas that you just tossed out about how to

make jewelry out of these tiny little things. The thing is, they are

easily breakable. So, it's not really a flexible thing to experiment a

lot with. Also, it's quite exclusive and expensive; not only

economically, but also thinking of what this material really is. It's

actual reindeer bone, made into porcelain, and the link to the buffalo

china, it’s horrible colonial history. I don't want to limit anything. I

want to be open to have these tiny little, super elegant, and super

expensive yet politically charged jewelry pieces, if that feels natural

or right in the context; or, I'm open for you to make other things. I'm

never putting boundaries on collaborations when I feel a shared

understanding.’

We are such a big group but spread in tiny minorities all over the globe. We need to be stronger for each other to have faith in the future, feel secure. We need to figure out solutions together

‘Although modern nomadism is a foreign concept for me, I can understand the need for this, for instance your need to choose a nomadic way of living which seems to break out of a set Western standard. For traditional nomadism there is also a need, a need to move for survival. This makes your perception of life, surroundings, time, well everything, more flexible, adaptable and open, I guess.’

If you stop and listen, or just breathe somewhere, the air smells different, the water tastes different, but why? What does that mean? That's when you realize that Chile and Detroit and Northern Norway aren't really that far apart.

‘I measure not in in kilometers or miles: it's more of a soul perspective and mind perspective, definitely. And talking about physical distance for me, I'm thinking just like our way of life, it's a need, you know, because we need to just adapt for survival. So our animals need to migrate for their survival and that's why we adapt. And that's why we bond to all of these regions in the same ways. They are equally precious for us.

And I think very similarly about the traveling I do for my profession. Yes, I can go to places for a holiday, but for me that doesn't have anything necessarily to do with life. Like where I go, for instance, to Guatemala, I don't know how to explain. But it is…’

Equally as precious.

‘Yes, it is equally as precious, the land in relation to people, animals, and the whole cycle. I tend to go back to places or travel because of need. Need is a key word both in our way of a nomadic life and the places I choose to work from when thinking globally like Chile, like Guatemala, like Canada when I have been there.’

Like you said, each place is just as precious. Home is me, and home is you, that is home for me, is the people and the reminders of being in places and spaces and people to form community with. This is a power queer people and indigenous people share. It's something we understand, and you can find commonality or home not in a house. We will need to build a network ourselves, that’s what we're doing right now, is building something that's outside of the institution that is a network, a support system to carry these commonalities, shows them, and allow people to question the ways in which they live.

‘We are such a big group but spread in tiny minorities all over the globe. We need to be stronger for each other to have faith in the future, feel secure. We need to figure out solutions together. The power of the modern nomad if we can call it that, which is different than traditional, is developing systems now to go beyond borders and support each other. At this time, it is more important than ever.’