Line Ulekleiv

Arlyne Moi

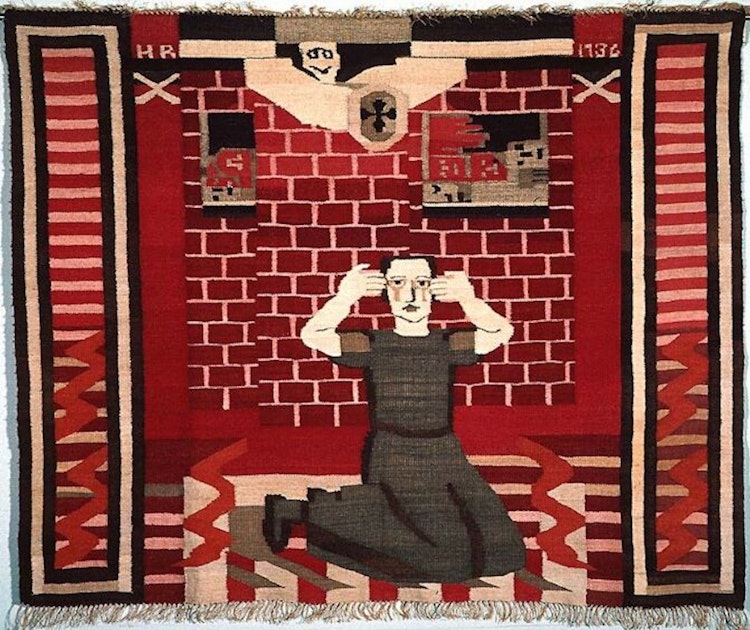

The Swedish-Norwegian textile artist Hannah Ryggen (1894-1970) wove tapestries using locally sourced wool and plant dyes from her and her artist husband Hans Ryggen’s farm on Fosen, by the Trondheim fjord; yet her activist tapestries offer a rich political commentary on global events such as Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia, the Vietnam war, and Nazism’s emergence in Europe. In this article by Line Ulekleiv, we are invited to investigate the relevance of Ryggen’s practice in contemporary society, and the reasons behind her rising popularity in recent years.

The weaver Hannah Ryggen (1894-1970) experiences renewed interest from the field of contemporary art. A self-taught weaver, spinning and dyeing her own yarn with plant-based dyes, Ryggen created works that came to be characterised as ‘Tendency Art’ – art with socio-political and critical contents. With the medium of weaving, she commented on Fascism and Nazism’s emergence in Europe in the inter-war years, and Norwegian politics in the post-war years.

Ryggen never drew preliminary designs before beginning to weave; she was experimental but had a clear idea of how the end result should look. Most of her pictorial weavings are characterised by an explicit social and political protest that is executed in a daring, original, and personal style.

No one followed directly in her footsteps, yet she is considered important, not least because she was the first Norwegian textile artist to be accepted as a bonafide pictorial artist. Her works, moreover, were purchased by Norway’s National Gallery1 and were, in 1964, the first textiles to be included in the Autumn Exhibition2 – a prestigious, juried event.

Before 1964, pictorial weaving was largely regarded as second-rate and ‘merely’ decorative; made by weavers according to a painter’s romantic, decorative cartoons. In Ryggen’s practice, there is an inherent tension and an interaction between crafts and fine art. But what is it about her pictorial weavings that appeals to the contemporary art public? What makes her art relevant today?

Ryggen’s influence

The Human Pattern, curated by Marit Paasche and Kunsthall Oslo, is the first large exhibition of Hannah Ryggen’s works in Oslo since 1986. In addition to showing eight tapestries woven by Ryggen, the exhibition creates complexity by including works by abstract artists such as the Norwegian modernist Anna-Eva Bergman and Gunnar S. Gundersen. In addition, Claude Cahun and Pablo Picasso are represented – these international artists were Ryggen’s contemporaries, and they shared her anti-fascist views. Finally, there are works by younger artists such as Ann Cathrin November Høibo and Kirstine Roepstorff.

This latter group draws Ryggen more explicitly into the present era, in terms of method and themes, but also in a more metaphorical sense — here through references to, for instance, feminism. All the above-mentioned participants are recognised as pictorial artists (the majority are painters), not people working with crafts, and this inclusion of Ryggen in the company of regular pictorial artists seems to be prioritised. The selection of artists supplements and deepens key aspects of Ryggen’s practice in an interesting way. The effect of flatness in Ryggen’s weavings is pushed to the extreme in a painting by Olav Christopher Jenssen, and the textile – the thread in the pictorial plane – can be found in several works.

The exhibition’s express goal is to expand the contextual understanding of Ryggen’s works and, at the same time, to recognise the influence she increasingly exerts on younger artists and art historians.

Ryggen’s artistic legacy

The exhibition Forms of Modern Life at OCA (Office for Contemporary Art Norway)3 also presents pictorial weavings by Ryggen, to be more precise, Gru (meaning ‘Horror’ or ‘Trepidation’) and Hitlerteppet (Hitler Tapestry), both from the 1930s. In this exhibition, Ryggen is situated in a trajectory of artistic development where simplified forms can be related to the communication patterns and political ideologies of modernity. The concept of art is here stressed as commonplace and user oriented.

A key point in the curatorial presentation of The Human Pattern is that Hannah Ryggen, undeservedly, has been largely forgotten – even though she, in 1962, held a hugely successful solo exhibition at the Modern Museum in Stockholm and represented Norway at the Venice Biennial two years later.

Her artistic legacy is claimed to be overshadowed by her biography, like a footnote in the story of her life. Living on a farm in Ørlandet with her artist husband, she was far removed from typical artist communities. This rural isolation is much discussed, especially in light of the fact that the reception of art in Ryggen’s own day was largely marked by a biographical orientation.

Much loved outsider

In the book Norges malerkunst (Norwegian Painting), the art historian Hans-Jakob Brun describes Ryggen as ‘our most loved outsider.’4 Yet, in the same breath, he points out that the artist Arne Ekeland, Ryggen’s contemporary, is often seen in a larger context, as someone who created political works developed through reflection; even though both Ryggen and Ekeland made these types of works in monumental formats. Ryggen’s isolation was, however, relative; she keenly followed current events and developments in modern art through newspapers, radio, and her own travels. This orientation is reflected through her style as well as choice of motifs. Her art was not created in a vacuum.

The claimed absence of Ryggen appears to be an exaggeration. She seems to have been with us the whole time. Art critic Geir Haraldseth points this out in his review of The Human Pattern on the website Kunstkritikk: Ryggen has been featured in a larger retrospective exhibition almost every decade since her death, and her artistic practice has been discussed in various contexts through group exhibitions, for instance in Fokus 1950 at Norway’s Museum of Contemporary Art5 in 1998, and in Bendik Riis Band at Galleri F 15 in 2009.

As good as art

The fact that Hannah Ryggen’s expressive, emotionally charged visual idiom is linked with painting is perhaps not surprising — since even she described her method as painting with woven yarn. She studied painting for a time and insisted that by following her own artistic principles, her craft-based works would be transformed into independent artworks.

There is a value judgment in this upgrade in status, which is partly reflected in the exhibition concept at Kunsthall Oslo (admittedly, the concept also takes into account more nuanced perspectives of the diffuse boundaries and interaction between pictorial art and arts and crafts). But seeking to upgrade the status of pictorial weaving from ‘craft’ to ‘art’ is non-productive, for it hinders pictorial weaving from having inherent value. The textile picture is legitimated by being included in the more dominant context of painting; it becomes ‘almost as good as art.’

Reluctance towards abstract art

If Ryggen preferred painting, why then did she take the cumbersome, slow, and less artistically relevant detour via the loom?

It would be correct to say that weaving as a practice, the textile materiality and control over colour nuances, all express something not necessarily transferable to painting.

Moreover, the commonplace and anti-elitist connotations of weaving probably fit well with Ryggen’s intentions and temperament.

The flatness and stylisation in her visual language was plausibly influenced by abstract painting and the push towards flatness, as advocated by the aesthetic theorist Clement Greenberg. This is despite Ryggen’s outspoken resistance to abstract art. Once, in an interview, she expressed exasperation over ‘all that chequered and striped art.’ But her works are also carriers of a unique textile tradition, a means of storytelling extending at least as far back as to medieval times.

A classic

Hannah Ryggen was one of the first Norwegian artists to use international conflicts as source material for her motifs in the 1930s; she wove images of Hitler and Mussolini into her textiles with the greatest matter-of-factness. This undaunted political expression permeating Ryggen’s oeuvre measures up to the temperature of contemporary art, and she becomes ‘one of our own.’

She is also an appealing bridge-builder between crafts and pictorial art – the two prone to behave like a mismatched couple embroiled in internal conflicts. The material-specific approach of traditional arts and crafts coincides with contemporary artists’ increasing involvement with concrete materials, especially their orientation towards textile expressions.

The increased attention paid to Ryggen is entirely positive. Her artistic practice can, with benefit, be discovered and reinterpreted by new generations – she is a true classic. At the same time, Ryggen’s works convince us of the need to exchange the crude, predictable categories of art with more nuanced categories that help us see the objects we try to study.