Reinhold Ziegler

Arlyne Moi

Tone Vigeland’s art springs from a direct encounter between her hands and her materials. For more than fifty years, she has created jewellery and sculptures that combine simple craft techniques with stringent aesthetics – works apparently liberated from any possible intellectual approach. Perhaps this is why people the world over describe her art as both timeless and placeless, and sometimes even magical.

Tone Vigeland has long been considered the uncrowned queen of Norwegian jewellery, even though she has worked exclusively with sculpture since 1995. If there is a common denominator for these two artistic disciplines, it must be that both are marked by painstaking craftsmanship.

What is it that motivates you?

‘The joy of working. The desire to make things. To have a calm, quiet environment that allows me to experiment and develop through trial and error. The curiosity of seeing the final result. It’s also inspiring to work in relation to a solo exhibition, to have a clear goal. But in the final analysis, it’s the process that is most important for me.’

How do you work?

‘I work directly with the materials. It’s important for them to be allowed to participate in determining the results. I sketch a bit throughout the process, testing different solutions, but I never make blueprint drawings others could work from. I work alone and use no assistants.’

Could you say something about what it is you seek?

‘I seek a personal expression. I try to listen to myself. That’s the most difficult part.’

Scandinavian design

Listening to oneself, and a tremendous capacity for working – these seem to be the most important threads running throughout Vigeland’s career. She was born into one of Norway’s most prominent artistic families and was raised in an environment influenced by strong artistic involvement. Her formal art education started in 1956, at the National College of Art, Craft and Design in Oslo; from there she went on to study goldsmithing at Oslo Vocational School. The next move was to the arts and crafts centre PLUS in Fredrikstad, where she worked as an apprentice between 1958 and 1961. After achieving a Journeyman’s degree1, she continued working at PLUS until 1963.

‘I produced a great deal during my school years. The works were very simple due to my limited skills, and it turned out that they were well suited for mass production.’

She developed a visual idiom that fit well with what, at the time, was described as Scandinavian Design: simple, rounded forms and smooth, uniform surfaces. The motto for this artistic direction was ‘a more beautiful everyday’. Mass production meant that her works came into circulation early in her career, and were appreciated by a wide segment of the public. Her most well-known products from this period are the so-called ‘ear loops’, which can be fastened to the ears without any special mechanism. The ear loops were a hit, and people still talk about them and want to buy them.

Many-faceted debut exhibition

After earning her journeyman’s degree at PLUS, Vigeland set up her own studio. In her free time, she began developing more independent works – things which did not need to fulfil the requirements of mass production. Slowly she began moving away from the simple, supple lines of Scandinavian Design and towards more complex formal expressions.

At her first solo exhibition, at Kunstnernes Hus in Oslo in 1967, one could see clear evidence of this. The exhibition consisted of one hundred works displaying numerous and varied expressions. For one series of pendants with double perforated patterns, she drew inspiration from Op Art.2 In other works, she assimilated ideas from non-European, traditional jewellery. Three exhibited works consisted of a mesh of many small rings, combined to create multi-jointed networks studded with stones and pearls. One of these pieces could be described as ‘artwear’: a combined wrist-hand-finger piece.

‘During that time period I often visited ethnographic collections, both in Norway and internationally. Among other things, I was fascinated by jewellery from India and Egypt.’

‘I seek a personal expression. I try to listen to myself. That’s the most difficult part.’

Flexibility

The qualities of flexibility and adaptability to the body’s contours, which were expressed in the bracelet-hand-ring piece, would eventually become a leitmotif in her works. This was despite the fact that trends in jewellery throughout the 1970s often moved in the opposite direction: towards liberating jewellery from the requirement of being comfortable to wear. But it would take almost a decade and many intermediate stages before Vigeland developed the flexibility that became her trademark.

‘Things easily become too stiff. A piece of jewellery should follow the body’s curves. So I became increasingly preoccupied with the jewellery’s ability to adapt itself to the body.’

In the mid 1970s she started experimenting with pre-fabricated chains, connecting them together with small rings. Using this technique, she produced a pliant silver mesh that could move this way and that, and follow the lines of the body. In 1976 she created a jewellery series using this type of mesh as a foundation for elements of gold and oxidized silver.

‘The silver mesh satisfied my desire to make jewellery that was pleasant to wear. The multiple joints made them soft and invitingly tactile. I’d been looking for a long time for a soft, sensory tactility – as a contrast to the hard metal.’

At her next solo exhibition at Kunstnerforbundet in 1978 – a wide-ranging exhibition with many different expressions – she won a great deal of attention and promising reviews for her pliant, multi-jointed jewellery.

Internationalisation

Also in 1978, Vigeland went to London and showed her works to Barbara Cartlidge, director of the trendsetting Electrum Gallery. Electrum was then a groundbreaker for modern art jewellery, treating it as fine art and equal in status to sculpture and painting. Cartlidge took in several of Vigeland’s works on commission.

‘It was extremely inspiring to be represented in an international jewellery gallery. Not least, it was exciting to see works by the other artists who were represented there, who worked in completely different ways and with completely different materials than we were used to at home in Norway. There were artists working with lacquered steel, textiles, plastic, and titanium, just to name a few.’

When invited to hold her first solo exhibition at Electrum in 1981, she nevertheless did not start exploring these new materials. She stuck to the track she was on: jewellery in oxidized silver and flexible silver mesh. This exhibition drew much attention to Vigeland’s works, and she came into contact with an international group of artists, collectors, writers, and curators. The Victoria and Albert Museum purchased a large necklace consisting of hand-forged, hammer-flattened steel pins mounted on silver mesh.

Nails

Jewellery with forged steel nails was also one of her chosen themes when she held another solo exhibition at Kunstnerforbundet in Oslo, shortly after the Electrum exhibition.

‘The year before, some friends had given me an old handmade iron nail. They had bought an old house and had found the nail while doing renovation.’

Vigeland used this enormous handmade nail to make a piece that looped around the neck and ended in a diamond set in gold. After this, she began collecting nails and pins in great quantity, forging them into feather-like elements and mounting them on a metal construction or a silver mesh.

The Kunstnerforbundet exhibition was a great success. Not least, it was noticed by curator David Revere McFaden from Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York. While in Norway selecting artists for a large exposition on Scandinavian Design, he saw Vigeland’s exhibition, commissioned a piece of jewellery from her, and invited her to participate in the expo. This was the start of an extensive American career.

USA

Her first solo exhibition in the USA was in 1983 at the jewellery gallery Artwear in New York. It was owned and operated by Robert Lee Morris, himself a jewellery artist. He represented a different, more voluptuous style than Vigeland was used to. Among other things, he experimented with how the pieces were exhibited and, like Vigeland, was concerned with how they draped around the body. In the exhibition, Vigeland’s works were presented in novel ways, for example, on plaster torsos or hanging in tree branches.

‘It was fun to be a part of this. It was crazy and chaotic. My works were well received, and it was a wonderful way to be introduced to an American public.’

In the '90s, Artwear closed and Vigeland started collaborating with Helen Drutt, a gallerist and collector with a particular interest in jewellery and ceramics. As one of the most prominent actors in the field, not just in the USA but also internationally, Drutt has written and lectured, curated and worked tirelessly to introduce contemporary studio-crafts to the public. According to Vigeland, this collaboration meant a great deal to her. In 1994, she mounted a solo exhibition at the Helen Drutt Gallery in Philadelphia. In addition to the well-known pliant jewellery, she presented a cap consisting of small metal squares set on-end and joined together with small silver rings. The work conforms perfectly to the wearer’s head and can fold like an accordion when not in use.

Unified form

In the latter half of the 1980s, Vigeland further refined her use of flexible silver mesh. First of all, the mounted elements were placed so tightly together that it now became difficult to see the underlying mesh. Secondly, she stopped using more than one kind of element in the same piece of jewellery. Regardless of whether she used cylindrical spirals, balls, or knots, the individual elements were repeated and became part of a larger, unified structure. She also stopped using clasps, hence the pieces also acquired a closed form. The mesh on these works forms a continuous loop without front or back. A good example is a neck piece from 1985, purchased by the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

By the end of the ‘80s, she stopped using silver mesh and started constructing jewellery from a range of geometrical forms, while still keeping to the ‘mantra’ of flexible, unified forms. The first examples of this were jewellery pieces consisting of square metal plates mounted with hidden rings on the back side. For a subsequent series, she used small silver sheets positioned tightly together and standing on-end. Her solo exhibition at Kunstnerforbundet in 1993 was devoted to this new direction.

Sculpture

In 1995, a retrospective exhibition of Tone Vigeland’s jewellery was held at the Museum of Decorative Arts and Design in Oslo. Portions of this exhibition then went on tour, first to Cooper Hewitt in New York, and thereafter to several other American cities, before moving on to Japan and Canada. Two venues were the Musée des Arts Décoratifs de Montréal in Quebec and the Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo. The show was reviewed in many newspapers including The New York Times and The Herald Tribune.

With the irony of fate, this retrospective exhibition would be her farewell to art jewellery. About the same time, she was asked by one of Oslo’s leading art galleries – Galleri Riis – to present a work in its project room. Vigeland took up the challenge and developed a sculpture consisting of several thousand parts, not unlike some of her jewellery. But the form needed to support itself without a body holding it up, so the elements were fused together so as to form a self-supporting structure.

‘I felt a great sense of liberation doing this project. But it was also the challenge that inspired me.’

Did you consciously decide to stop creating art jewellery?

‘More or less. After the first sculpture, I was invited to do a solo exhibition at Galleri Riis. When I said yes to this, I knew I couldn’t work with jewellery and sculpture at the same time. I needed to concentrate on one thing.’

From pedestal to wall

After the initial sculpture, she created a series of sculptures consisting of stones ‘packed into’ lead. This project was less controlled than she was used to. Indeed, she had collected the stones herself at the seaside, but the labour of encasing them in lead was difficult and resulted in unforeseen traces of hammering and joining. The works were exhibited at Nordjyllands Kunstmuseum in Aalborg, Denmark in 2000.

In 2000, Vigeland also held her first solo exhibition at Galleri Riis. She presented six sculptures consisting of lead elements mounted on metal mats. Two years later, she directed her focus away from the pedestal, and began using the wall as the starting point. The result was a wall work composed of a great many steel wires with lead shapes appended to their ends; each wire bent down towards the ground to form a characteristic arch. This work was purchased by the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Texas.

Four years later, in 2004, Lillehammer Art Museum opened the exhibition Tone Vigeland: Jewellery and Sculptures 1980-2001. This is the first retrospective exhibition to include her sculptures as well as jewellery. An additional overview of her art had come out in book form the year before. Along with extensive photo documentation, the monograph Tone Vigeland: Jewellery & Sculpture (Arnoldsche Verlagsanstalt) contains a well-researched essay by Cecilie Malm Brundtland.3

The tactile dimension

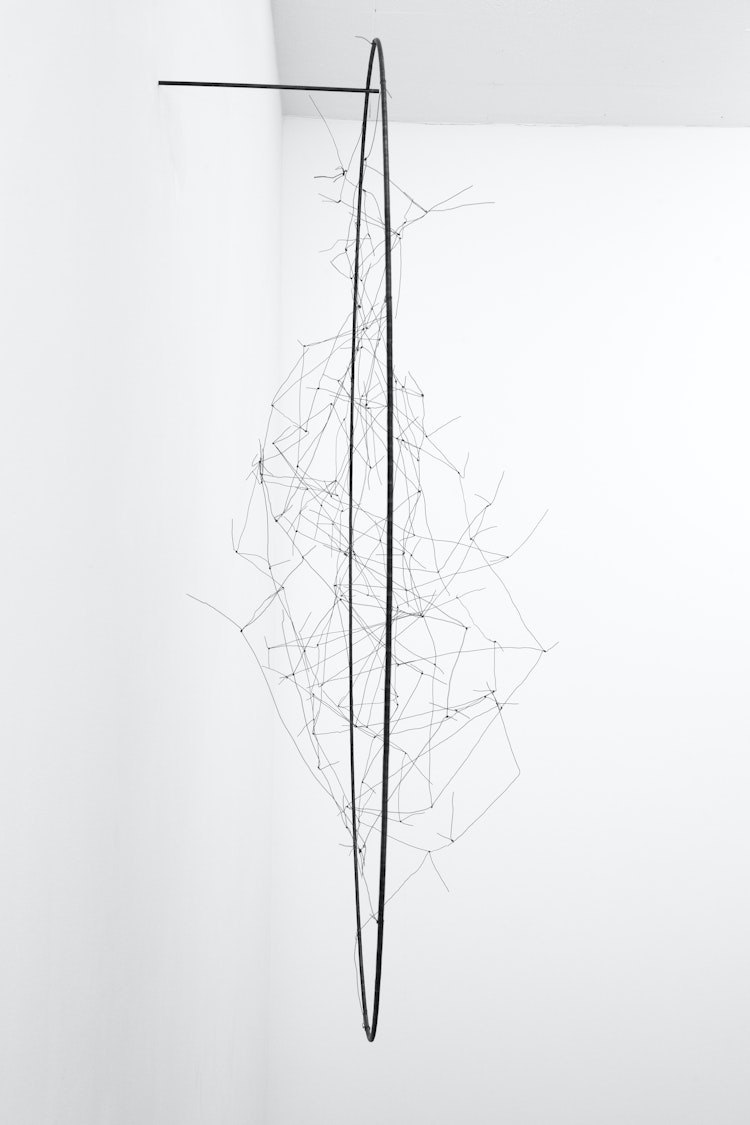

Thus far, Vigeland has held five solo exhibitions at Galleri Riis. The most recent, in 2011, presented sculptures that engaged with the walls, floor, and ceiling in ways that interacted directly with the room’s architecture. Made with steel rods and piano wire, the works’ construction made them easily vibrate. Many viewers commented on their lightness, mobility, and craftsmanship.

The art historian and critic Øyvind Storm Bjerke, in his exhibition review for the newspaper Klassekampen, admitted that he had to exert himself not to touch the sculptures: ‘Considering this tactile appeal in the context of Vigeland’s art jewellery, one can say that the dimension of touch, through the sculptures, is sublimated to a higher level.’4

Now 73 years old, Tone Vigeland is still actively working as an artist. At the time of writing, however, she will not divulge her next project.