Heidi Bjørgan, Bjørn Inge Follevaag, Feng Boyi and Wang Dong

Norwegian Crafts and the artists

In this conversation we meet the curator team behind the Sino-Norwegian ceramics exhibition Beyond G(l)aze, consisting of two Norwegian and two Chinese curators: Heidi Bjørgan, Bjørn Inge Follevaag, Feng Boyi and Wang Dong. Here they discuss their experience working with the exhibition, after the initial showing of the exhibition in China.

The Sino-Norwegian joint exhibition Beyond G(l)aze has three defining traits. First of all, it is an exhibition that marks a collaboration, exchange, and juxtaposition of Chinese and Norwegian contemporary art. Secondly, all artworks are made from clay, so there is a material constraint. Thirdly, the title Beyond G(l)aze refers to the fact that the artworks in this exhibition transcend the forms and patterns of traditional ceramic art. This approach to ceramic craft as a medium for contemporary art creation expands existing aesthetic habits or methods in ceramic arts. What we hope to show audiences in China and Norway is how the participating artists engage in experimentation and transformation of this traditional cultural resource, and the many possibilities the ceramic medium possesses within a contemporary art context. One can see how these artists understand and utilise the material, and perceive the commonalities and differences in their visual transformation of the medium, thus continuing a longstanding cultural exchange between these two nations.

Chinese ceramic tradition encompasses thousands of years of history and experience, whereas we tend to think of the Norwegian ceramic tradition as substantially shorter. It is extremely interesting to observe how artists from two so different cultures have approached the technical, artistic and crafts related challenges and to observe to which extent historical and classical traditions are evident in the works presented in this exhibition. Beyond G(l)aze targets a Sino-Norwegian audience in terms of challenging traditions and history, freedom to experiment with a classical material and the artworks’ relevance in the field of contemporary art.

A dialogue between the curators is not only a dialogue about an exhibition, but also about cultural context, identity, dissemination of knowledge and curatorial practices. To this end, as a Chinese and Norwegian curatorial team, we have engaged in a dialogue through four questions. From our respective cultural identities, knowledge, and curatorial experience we try to discuss the exhibition and the exchange produced by this process. Our responses to the questions can be viewed as a manifestation as well as a supplement to the mechanisms of exchange between the two countries, beyond the communication inherent in the works in Beyond G(l)aze.

As a curator, how do you evaluate the use of the traditional cultural resources represented by ceramic traditions in the production of contemporary art?

Feng Boyi: In a general sense, traditional cultural resources are the main substance and method of cultural transmission, allowing us to form a community of shared values, a shared attitude of affirmation of certain values, as well as our aspirations and expectations towards traditional classics. They have virtually become a proactive cultural choice. To carry on the transmission of tradition has become an inevitable logic of artistic creation. But in a time when traditional cultural resources are facing unprecedented challenges in a postmodern context, cultural transmission is often manifested through a constant utilization and alteration of traditional cultural resources, a component of overall cultural transmission. As I see it, this has, in turn, enriched the spiritual content and artistic expressiveness of these traditions, which in itself is a reaffirmation of traditional cultural resources.

Heidi Bjørgan: As a curator and artist, I see the use of traditional cultural resources in the production of contemporary art not only as a choice, but as the legacy that connects the old with the new. I believe this to be a question of skills and knowledge, and history is rife with examples of new techniques and expressions. In postmodern and globalized times, borders and limitations change. We are under a continuous influence of new impulses and expressions. Still, the typical characteristics, rooted in tradition and culture, are not erased but remain latent in our cultural heritage. When different traditions meet, in a singular work or in an exhibition like Beyond G(l)aze, a constructive dialogue can be useful, in which there is a potential for valuable new perspectives, almost as in the production of new knowledge or insight.

Wang Dong: I think contemporary art systems that make use of traditional cultural resources is a key feature of a postmodern approach to art. As for Chinese contemporary art, this has been evident since 1990. Chinese contemporary artists have been strongly influenced by globalisation, particularly by a Western influence on art, but also strongly subjected to the legacy and development in their own contemporary culture and tradition. Thus, the utilisation and appropriation of traditional cultural resources is both a requirement for the development of Chinese traditional culture as well as an inevitable path for Chinese contemporary art as it clashes with other cultures. In this postmodern, globalised context, many aspects such as lifestyles and ways of thinking are converging and fragmenting. Artists who grew up in China and received their education there think using philosophies rooted in Chinese traditional culture. Their artistic creations use postmodern methods to present the use and transformation of Chinese traditional culture through its contemporary use, while providing the world with a new opportunity to understand Chinese traditional culture. Chen Yifei and Xu Bing are examples of this. At Chen Yifei’s first solo exhibition in 1983 at Hammer Galleries in the United States, the artist presented works portraying Chinese landscapes created using oil painting methods familiar to the West. In 1994, Xu Bing transformed the letters of the alphabet into components of Chinese characters, creating a “New English Calligraphy” of English writing that resembled Chinese characters. This utilisation, transformation and appropriation of images and writing from Chinese traditional culture represented a new model for the development of Chinese traditional culture while also offering an opportunity for China to participate in a new global cultural process, adding a new vitality and significance to it.

Bjørn Inge Follevaag: To sum up what my colleagues already have emphasised: everything relates to everything. And I would also like to draw from the words of the Indonesian artist Heri Dono during his exhibition in Bergen in 2006: Without folk art there would be no fine art! Whatever we do today is based on a heritage from those who went before us. This is particularly evident in clay-based arts because of its long tradition. As Heidi notes, we are no longer restricted by borders, and can access the world through the click of a mouse. The dissemination of my local reality has the potential to become global. Of course, this accessibility also means that the same local reality has the potential of becoming lost, overlooked, or ignored. I feel, however, that culture, history, and tradition is the basis we use to invent something new, and thereby also significant in a postmodern and globalised context.

How do you understand and define the exhibition theme in Beyond G(l)aze? What is the basic standard you have used for selecting the artists?

Bjørn Inge Follevaag: For me the theme coins the words gaze and glaze: Gaze as being able to see beyond the material of the object, and the glaze as its classical surface. Our wish is for the audience to be able to see the artwork as expanding far beyond its material basis through the diversity of expressions the artists represent.

Heidi Bjørgan: As the title indicates, I would simply say that we invite the audience to look beyond the immediately familiar. By juxtaposing works from two very different cultures we open up to new perspectives and reflection on a familiar as well as an alien culture. Many factors come into play; the most striking is perhaps the concept of communality versus individualism, as in Ai Weiwei’s Sunflowers and in Ingrid Askeland’s big bottle of beer. This becomes a highly potent dichotomy, especially when comparing art from the world’s most populous country with art from one of its smallest countries. It is almost like it vibrates.

Feng Boyi: I will have to repeat what we said in the introduction: the exhibition aims at showing how Chinese and Norwegian artists engage in experimentation and transformation of ceramic as traditional cultural resource within the context of globalisation, and the many possibilities the ceramic material has as a medium in a contemporary art context.

Wang Dong: This is an exchange exhibition where Chinese and Norwegian artists use ceramics as a creative medium. The title Beyond G(l)aze is a reference and a constraint on their creations as well as the consideration and analysis of contemporary ceramic art and ceramic culture. Each artist is exploring this traditional medium in new ways rooted in the history, culture, and artistic ecology of ceramic in their own countries. Therefore, when inviting and selecting exhibits for this project, a key criterion has been ‘innovation’. This ‘innovation’ refers to how ceramic has been used to create new expressions, and how this can change or expand the public’s experience of the aesthetics of ceramics, and whether their works are able to offer a new visual perception to the past and contemporary from a new angle.

Heidi Bjørgan: In this case, it becomes vital to remain conscious of traditions at the same time as presenting new ideas and positions towards the world and reality.

Bjørn Inge Follevaag: I would like to add that another important focus on my part has to a large extent been communicability. How do Steinar Haga Kristensen’s works relate to the Norwegian public, compared to the works of Lu Bin? And how about Liu Jianhua’s work? How does the work speak to, or about, the individual spectator? It has been important to be able to communicate content rather than nationality, while remaining very aware of the bilateral aspect of it.

In this group exhibition focusing on ceramic as medium, what is your evaluation and your comments to the similarities and differences between the Norwegian and Chinese artists’ works, in terms of concept, production and visual language?

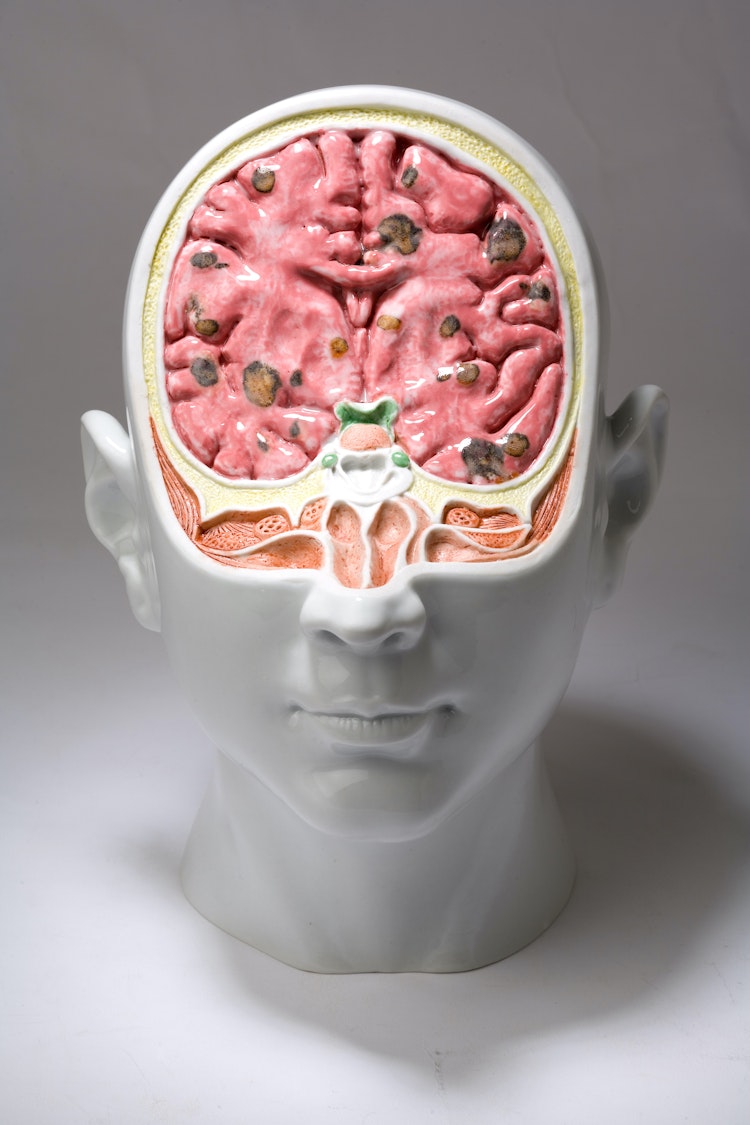

Wang Dong: Ceramic has been a part of mankind’s ancient history and played a very significant role in human daily life as well as in human aesthetic experience. Ceramic remains present in our lives, but mostly as tools and vessels. In Jingdezhen, the capital of Chinese ceramic art, ceramic is mainly used as a carrier for other art forms, as seen in ceramic print art and decorative vases. Ceramic art has been placed behind painting and other arts, serving much the same role as the canvas. This exhibition includes 16 artists from China and Norway, and they have all engaged in different artistic experiments and expressions regarding the medium itself and its cultural legacy. Their works offer a direct reference to this body of ceramic culture, and challenge the perception of ceramic culture as a historical relic through visual symbolism solidly grounded in contemporary art.

Feng Boyi: I think that, in the eyes of the artists participating in this exhibition, mankind’s ability to create models to deal with their complex experiences is extremely weak. Therefore, we need to constantly change perspectives to express those experiences and create new forms to fight off the constant threat of either stillness or chaos, allowing for a form of release for certain narratives that differ from tradition or have been stifled by it. Thus, the participating artists are not so much utilizing the medium of ceramic as engaging in mutually destructive, creative, or constructive experiments in the various forms, aesthetic tastes, and patterns of ceramic art throughout history. Take for example Lu Bin’s 'self-destructive' objects and Torbjørn Kvasbø’s heavy sculpture series. Their explorations are supported not only by their unwillingness to settle into a fixed style for themselves, but also by their ideas and obsession with ceramic art in itself. In other words, their creations use postmodernist methods in an attempt to dispel the interpretive model of dualist opposition between original and imitation, surface and depth, real and unreal.

The value and significance of the selected works lies first in their provision of a diverse set of concepts for a new understanding of ceramic art, while showing the artists’ familiarity and love for the medium. Also, it implies dealing with tradition from within tradition, using the energy still lingering within the classics to destroy their ability to control and thus change the direction in which that energy works. By revealing the limitations of accepted visual models, they have raised a challenge against the authority of a singular narrative. To be precise, they are using the multiple relationships between the individual, tradition, and history to present their thoughts and understandings of the uncertainty and multiplicity of tradition, our current time, the future and history. In this process, these once familiar mediums have been made unfamiliar in order to control the expectations of the viewer and allow the viewer to take in the surprise produced by a new model and perspective, and the freedom that follows discarding the rules of traditional ceramic art. It also makes the viewer aware that the artworks they are viewing are not ceramic works in the traditional sense but “new” visual art that is the result of utilization and execution. The visual text has been deeply inscribed with their individual creative imprints, as well as the expression of the commonalities and differences between the Chinese and Norwegian artists.

Heidi Bjørgan: As for the similarities, I agree with Wang Dong and Feng Boyi’s reflections. Still, I would argue that Chinese works in this exhibition relate to the contemporary in quite a different way from the Norwegian works. Perhaps an entirely different sense of social responsibility is at play. To coin a phrase, one could say that the Chinese artists see the individual through the eyes of society, whereas in Norway it is the exact opposite. And the status of the artist in Chinese society also seems much higher, and the art market much bigger. This, however, I guess also represents a limitation for the arts in the sense of commodification of art and a market orientation.

In China I felt that the artists had access to production assistance as well as opportunity to work in much larger formats. They seem much more bound by classical tradition and the opportunity to produce large scale works, whereas the Norwegian artists seem more playful, more open to blend expressions and less tied to traditions. The Norwegian artists seem to have more of a hands-on relationship to the production process. This, of course, refers to the artists’ working conditions. It gives more freedom, but is limiting in terms of format etc.

Wang Dong: I guess what Heidi Bjørgan means by ‘playful’ is that the Norwegian artists have already broken away from the approach to traditional ceramic as a craft to explore new possibilities for ceramic as a material in contemporary society, as well as investigating new visual expressions within the realm of contemporary art. The works by Chinese artists are larger in format, and as they seek out more possibilities for ceramic as a material they have also engaged in reflection and criticism on the heritage and state of Chinese ceramic culture. Their art is inextricable from the Chinese social and cultural reality, and they are marked by the intersection of individual life experience, memories, and the state of the nation.

Bjørn Inge Follevaag: From my perspective I first assumed that I would be overwhelmed by the massive Chinese tradition and the abundance of technical and artistic resources available to the Chinese artists. I also assumed that the relatively short history of Norwegian ceramic art would put us at a disadvantage. Not so at all. In my experience the Chinese artists are less concerned with the material than with the artistic outcome. Ceramic is merely a tool for expressing sentiments or creating references in the artwork. And perhaps, like Heidi Bjørgan and Wang Dong imply, the Chinese perspective is much more communal and imbued with a social awareness–critical and political in essence. The Norwegian artists are much more focused on a personal perspective and viewpoint, with references that are less politically charged. The technical qualities, production processes and skills involved are impressive in both countries. It may, hopefully, be difficult for the audience to distinguish between which works are Norwegian and which works are Chinese.

As a shared project between China and Norway, how have you as curators experienced Beyond G(l)aze as an exchange project?

Feng Boyi: ‘Exchange’ implies communication and understanding, rather than attempts to break down the boundaries between people or to overcome barriers between us. Exchange is not about protecting one’s turf or holding fast to your own ideas and pushing them on others. The outcome may be satisfactory, or it may actually erect barriers atop a foundation of understanding, just like any interaction between people. One of the main goals of our joint curation was of course the hope that through placing the works of artists from two countries together, exhibiting them at the Suzhou Jinji Lake Art Museum in China and the KODE Art Museum of Bergen, Norway, we could present an attitude and approach of mutual understanding and tolerance and to reflect the outcome of this ‘exchange and dialogue’. We can never be the same, Me becoming you and you becoming me. The best situation and effect are to use ‘exchange’ to describe and supplement this vocabulary deficiency about the process that, in my opinion, naturally deepens our mutual understanding and knowledge.

Heidi Bjørgan: Again, I will agree with Feng Boyi on his reflections on what an exchange project is about. As for my personal experiences, I was most surprised by the Chinese unconditional respect for tradition. I would have expected much more liberty, but with hindsight I see this perhaps as a consequence of social and political history. Compared to China, Norway has no significant tradition at all to refer to in terms of clay-based art, so it may be difficult for us to understand the pride Chinese artists express for the material. It is also interesting to note that ceramic art in Norway is dominated by female artists, whereas in China it seemed almost exclusively male. I was also impressed by the respect we were shown as curators in China, exemplified by a complete faith in our professional judgment. But interestingly enough, despite cultural differences, we seemed to agree on, share professional opinions on and respect each other’s selection of works and artists.

Bjørn Inge Follevaag: For me personally this has been a very rewarding process. I have had the good fortune of working with Chinese artists since 1988 and know the culture fairly well. The cooperation between the producers Norwegian Crafts,1 the curators and partnering museums have been excellent. The ties we are creating on a professional and academic level with our Chinese counterparts are invaluable.

I still think it is important to acknowledge that the working conditions and tempo in our two cultures are massively different, which leads to communication challenges and the occasional glitch in production in terms of workload on the Chinese side and the Norwegian side. China is constantly establishing new museums and art institutions. People work long hours and our curatorial partners are constantly on the move. The Chinese curators work with multiple projects simultaneously, whereas we on the Norwegian side have had the opportunity to focus solely on this singular project. As for the institutions, it is generally accepted that the working day ends at 4 o’clock in the afternoon.

Wang Dong: As a joint curatorial project between Norway and China this transnational exchange can be seen as a challenge and opportunity. I think the challenges––like those Bjørn Follevaag notes––are mainly subjective, and experiences with the exchange process will be based on personal and professional issues on the two sides. The opportunity lies in the possibility of opening up a window of knowledge through international exchange as well as adding new perspectives to the field of clay-based art, and to discuss the state of the traditional versus the contemporary.

The professional judgment is consistent between the Chinese and Norwegian curators, and the cooperation has been smooth. In other words, although we speak different languages, our vision for the exhibition is shared. Ceramic, as a part of ancient Chinese history and cultural art heritage, has once again been given the opportunity to communicate cross-regionally. I sincerely hope–and believe–that the two countries in this joint exhibition can provide a visual specimen and reference for future development of contemporary ceramic art, and that this art of communication without borders becomes a model of collaboration.

Feng Boyi: Looking back now, the outcome of this exchange is not what matters. What matters is the artistic experience that arises from active involvement in this process. The outcomes of various choices made along the way are rooted in many different factors, including the different histories, cultures, and memories of the two countries, as well as the taste and character of the individuals. As a result, the artworks presented in the exhibition hall are the differing forms of expressive methods used by the artists from these two countries participating in this exhibition. Is it good? Is it bad? It differs from person to person. It may be complicated, but it is certainly not a simple dichotomy. That is because the various questions of history, reality, individual predicament, and identity are always more mixed and subtle than we imagine, predict, or deduce. The truth is that communication between individuals within the same cultural context is already difficult, let alone communication between individuals of different cultural and social environments. Perhaps this is the state of deep exchange or exchange in the true sense in the word. Perhaps we could call it the ‘utopia’ of ideals emerging as a ‘heterotopia’ in reality.