Monika Svonni is a multi-disciplinary artist living in Jåhkåmåhkke. Her oeuvre consists mainly of textile collages incorporating pewter thread embroidery and reindeer hide, but she also works with wood carvings and sculpture in a variety of materials. In this interview by editor and artist Carola Grahn, we are given an introduction to Monika Svonni’s work, which has been produced over many years, as well as to her outlook on life and art.

“There really is no depth to me,” she says, when I insist that she tell me more about the subjects in her pictures. However, her art belies this statement. Several of her subjects (we’ll return to the materials in a bit) involve near-realistic depictions of the Sami drum, but her colourful mountainous landscapes, which are rich in animals and plants, also contain elements that can be either immediately or abstractly connected to the Sami spirit world.1 What could this be, if not depth?

Might it be the fact that Monika never attended a major art school that makes her so averse to any attempt to use big words to label what she does? Or is that simply a consequence of her personality? She doesn’t enjoy being the centre of attention, and she’s hesitant to agree to exhibitions because it commits her to attending the opening and other events. She’s not the kind to claim a lot of space; her shoulders are narrow, her posture rigid, and her gaze an intense, bright green. Her voice is soft, but she never seems unassertive; on the contrary, she knows what she likes, and her art is subject to a well-defined order. Monika often works with symmetry, straight lines, squares, and perfect circles.

“I want to be free,” she responds, over and over, whenever I ask a question somehow related to the reasons why she hasn’t exhibited more often, or sought to make more of a mark, than she has.

Monika Svonni was born in 1948 and turned 74 this year. She has been creating for more or less her whole life. Her spacious house in Jåhkåmåhkke/Jokkmokk is full of art, both her own and her father’s. It has furniture and interiors that Monika has decorated and redesigned herself.

Her father, Karl-Gustav Andersson, was a painter from Västerås in Sweden. “This kind, I mean,” she says, and mimes rolling paint in the air. In his spare time, he pursued oil painting, and when he retired, he followed his lifelong dream and enrolled at the Pernbys School of Painting in Stockholm for six months. There are some copies of expressionists in her home, including one of The Night Cafe by Vincent Van Gogh. They are intermingled with traditional duodji, items either inherited by Monika or made by her mother, Anna-Kajsa Åstot. Anna-Kajsa knew most of the crafts: she could sew, weave, do carpentry, and make mosaics. These creative expressions were simply natural aspects of everyday life, as well as sources of inspiration for the children. Her maternal grandparents were reindeer herders based in Sijddojavvre/Sitojaure, where Monika still keeps a summer home. She appears every bit as fearless about mastering various materials as her mother was. When we cross a threshold adorned with carved, colourful fish, I’m reminded of Lásságámmi, Áillohaš's2 home in Ivgobahta/Skibotn in the North of Norway, and of Karin and Carl Larsson’s home at Sundborn in Dalarna in Sweden.

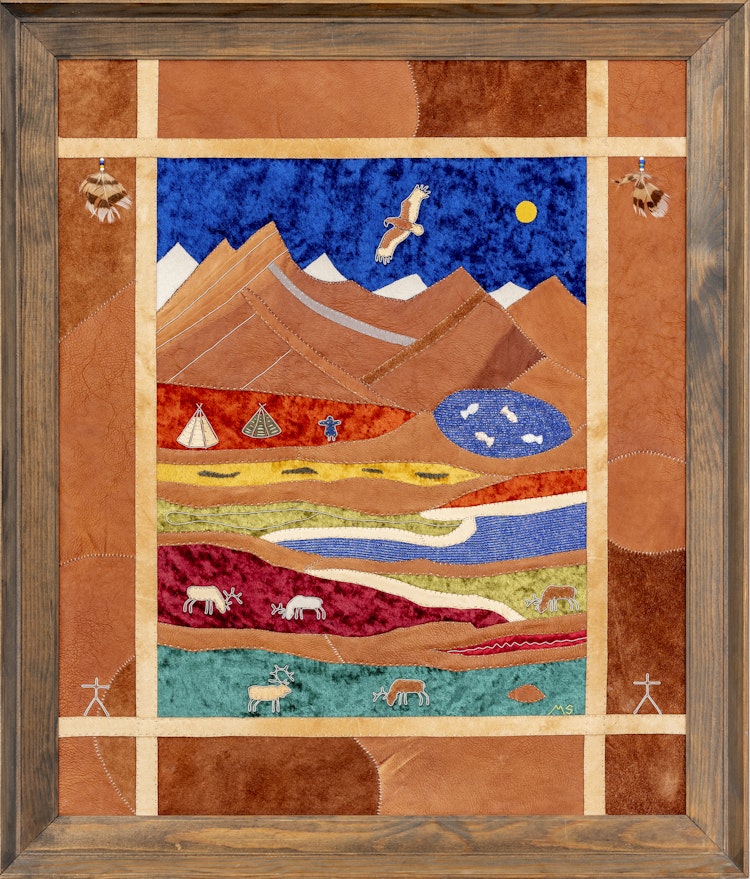

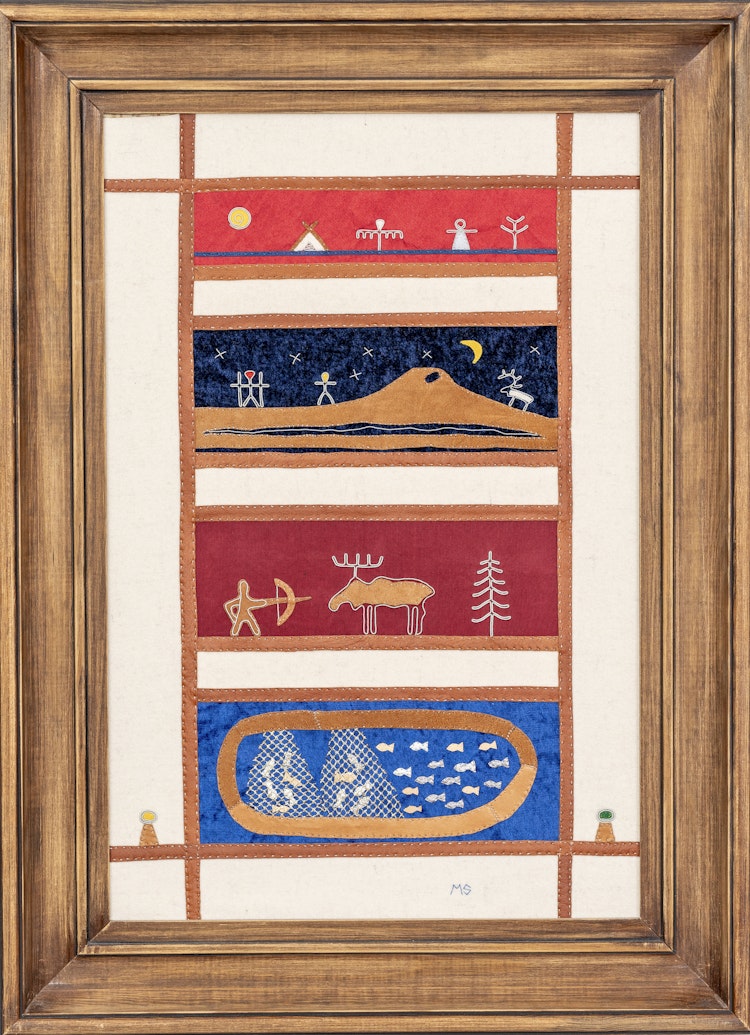

Monika’s oeuvre consists mainly of textile collages that incorporate pewter thread embroidery on reindeer hide and fabric. Anybody familiar with Sami tin thread embroidery from the Lule and South Sami gabdde will instantly recognise this beautiful craft.3 Monika studied crafts at the Sámij Åhpadusguovdás (Sami Educational Centre) in Jåhkåmåhkke/Jokkmokk, but her art is far removed from the traditional duodji.

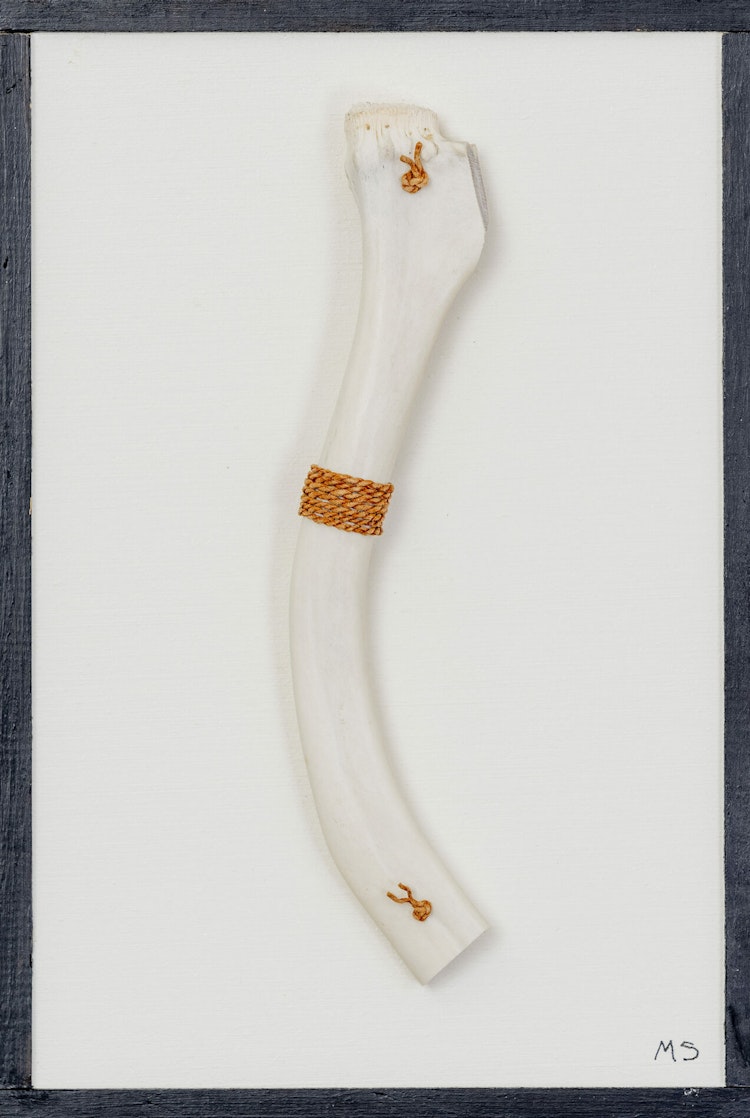

“I’ll tell you one thing,” she says, with fierce determination. “I don’t do conventional Sami crafts. What I do is to compose my works in my own way, using materials I enjoy working with, and not worry at all whether something conforms to or breaks with tradition.” Her art is reminiscent of figurative painting. However, it has the peculiarity of often being structured in a way sometimes seen on Sami drums, where different worlds are placed on top of each other in layers. The subjects are mainly depictions of mountain scenes, animals, humans, and Sami spirits. Over the years, she has also made a fair number of carved, painted wooden portraits, and a series of abstract stick and horn sculptures. These sculptures originated in Sijddojávrre/ Sitojaure, where she has simply had to work with the materials she has been able to forage. She might look for something useful in the woods, or under some old shed or other. Monika sees materials everywhere she looks. A wooden board, pocked with holes from nails, has been transformed into an abstract river of wood and wool.

“Nature made that one. It’s not mine, you see,” she explains when we discuss another stick sculpture. It’s as though these organic and crooked materials represented her own personal quest for harmony and order.

Monika has two thick binders full of pictures of artworks she’s sold, but she seems to have lost interest in documenting her work around the time photography went digital; the last few decades are barely included at all. For many years, she used to open up her cellar, where she keeps her studio, to sell her works during the Jokkmokk Winter Market. She also has a very neat and tidy wood shop down there, which she shows off proudly.

“That saw is worth its weight in gold!” she bursts out with a big smile. She does her morning exercise in the cellar, surrounded by her artworks, half-refurbished furniture, black-and-white photos of relatives in gákti, and embroideries in various stages of transformation. As she dances away down there, it seems like she’s pondering and processing what she has done.

Despite the large number of artworks she has sold, and the great amount of time she has spent on creating them over the years, she’s never thought of art as her main occupation. She’s a qualified medical secretary, and worked as one for almost ten years, including a stint at Huddinge hospital when it had just opened. However, she found herself longing to go back north, had children, and founded the Sámi Girjjit publishing house in collaboration with her husband, Lars Göran Svonni. Sámi Girjjit was one of very few publishers to focus on the Sami language, and they would go on to reissue the important work Muitalus sámiid birra4 by Johan Turi, as well as publishing other significant titles. Monika appreciated the freedom and independence of working from home. She appreciates solitude, and finds the best inspiration when she’s walking around in the woods and the wild by herself. Her ideas can be brought to full fruition as long as she remains inside her own bubble.

And perhaps this is the very thing that is so captivating about Monika’s art: the way she depicts freedom itself, in an eagle over a bright-blue sky, or a tranquil reindeer resting on a spot of snow. How she can make the vast vistas of these mountains seem to point inwards, to the 'expanses within'5 as Áillohaš would probably have put it.