Sarah Hudson (Ngāti Awa, Ngāi Tūhoe and Ngāti Pūkeko) has been an admirer of textile artist Ron Te Kawa’s practice and champions his unique approach to sharing Indigenous narratives and stories from te ao Māori (the Māori world) through toi tuitui (art making using sewing and fabric). In this article, Sarah Hudson explores Ron’s practice through the celebration of play and aroha (love), resilience and punk energy, and loud and rebellious joy.

I first saw Ron Te Kawa’s work at a Māori artist-run space, Taneatua Gallery, in 2017. Using his textiles as props, the artist performed a play about one of our significant star clusters, Matariki (also known as Pleiades, the rising of the star cluster Matariki signals the Māori new year). I sat on the grass with my then two-year-old on a sunny afternoon, surrounded by Māori families. We were captivated by our creation narratives and our reality being shown in a new light. I had never seen so much colour, so much visible visceral affection put into any artwork, and it was a joy to see Māori love being expressed in a bold, unapologetic way.

There are many reasons why I had never experienced Māori expression like that of Ron’s practice on that day. As Indigenous people, we navigate the complications of colonisation every day; this can be difficult and tiring. We experience expectations of speaking our native language, having a certain skin colour, being a cultural representative and, of course, contributing back to your community.

These expectations exist as layers in our being. They are present and persistent due to continued external pressures and internal, intergenerational resilience. Systematically and continuously, our identity as the Indigenous people of Aotearoa is disputed. We have to push, work and focus on surviving to get to thriving. Some of the expectations are a motivating and comforting call from our ancestors to contribute, participate and enact our agency as Māori. But some of the expectations are completely colonial fabrications of what constitutes a ‘good Māori’ or a ‘worthy Māori’, and perhaps this exposes the default being a ‘bad Māori’.

There is a high performance standard for contemporary Māori art, and perhaps being Māori in general. In an art context, these high standards are a way that Māori artists prove and maintain our worthiness. We take this role seriously; you can see it in our serious art.

Not all facets of Māori art are serious, it’s not all slick and polished; but that’s what we see the most.

Being serious, and striving for perfection, often cuts out the multiplicity of ways that we are Māori:

the care,

the mess,

the fun,

the mistakes,

the LOVE we pour into being Māori, into being Māori artists.

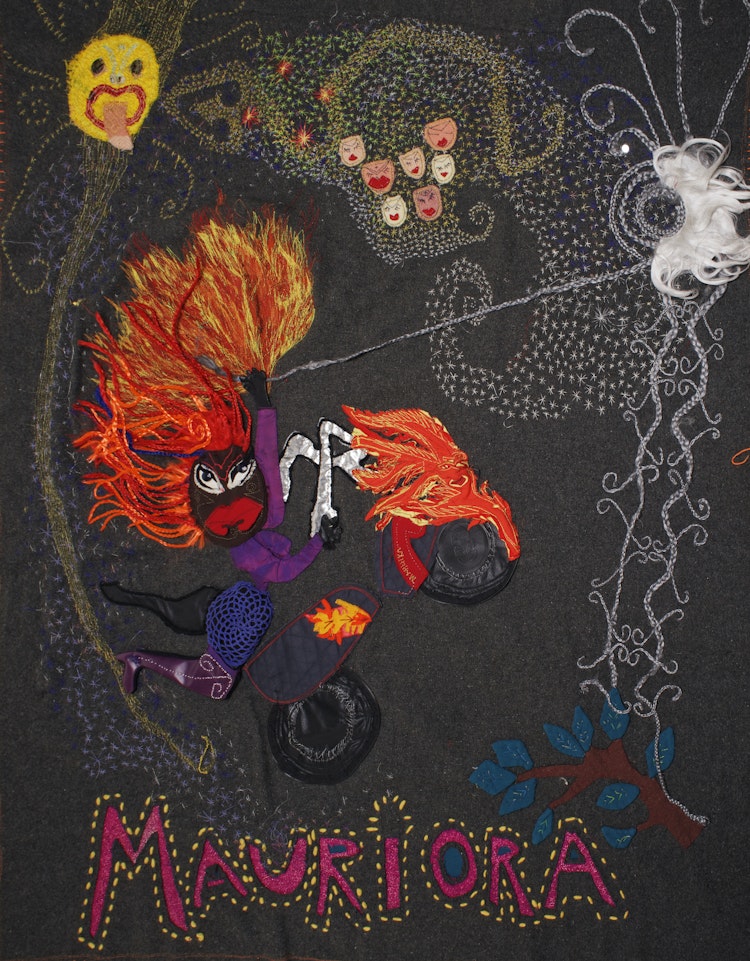

One contemporary Māori artist who rebels against the scourge of being serious is Ngāti Porou (Māori iwi traditionally located in the East Cape and Gisborne) textile practitioner Maungarongo (Ron) Te Kawa. He makes loud and loving quilted works that have been exhibited in art institutions across Aotearoa for more than three decades. Many Māori artists experiment with elements of fun and play in their studio practices, but it’s unusual to have those playful, joyful moments come through into final exhibition pieces.

The way Ron Te Kawa depicts Māori deities is not typical. There are no rippling muscles here – these iterations don’t seem to be influenced by Western beauty ideals and are comfortingly familiar to our lived experience as contemporary Māori. Indigenous audiences can find great solace and affirmation in that.

A significant deity in Māori culture is Hineteiwaiwa (guardian of childbirth and the arts pursued by women). She rules the realm of Te Whare Pora (the house of weaving) – weaving, sewing, female creativity and childbirth. She’s a powerful figure who plays an important role in many contemporary creative practices. In 2017, Ron Te Kawa created a textile work portraying Hineteiwaiwa on a motorbike. It excited me, it impressed me, it made total sense to me.

Translating Hineteiwaiwa in this manner brought her closer to me as a viewer.

She transformed:

from a deity on a motorbike,

to an aunty on a motorbike;

she’s now my aunty,

she’s an aunty that I want to be.

Bringing in some grit and edge to our deities makes their teachings more relevant and memorable. Of course she is on a motorbike, she’s the deity of childbirth – she’s got places to be!

An empowering way we can recentre Indigenous knowledge is through our customary narratives. They offer an opportunity to reconnect and reaffirm relationships with ancestors and deities. The tools of colonisation have been enacted to sever us from maintaining these relationships; the act of reconnecting can be big, serious business.

Our deities have been depicted by artists and those visual representations have then been reinterpreted throughout the centuries. Unfortunately, there are a few tropes that get overused: I constantly see images of our deities, and ourselves, using colonial tropes to express our Māori identities. Stereotypes like the Māori maiden (hyper-feminised, representing intermarriage and fertile land to be conquered) or the Māori warrior (hyper-masculine, representing inherent savagery that must be tamed). It’s hard to talk about Māori identity without seeing the systems that have tried to erase the Māori world come to the fore. Having the tools of colonisation consistently interject in the ways we express ourselves is tiring.

No matter how they’re visually represented, our deities are sacred, and always will be, when we can connect, honour and learn from them in ways that are relevant and meaningful to us, today. As if the visual representation of divine supernatural beings wasn’t a big enough task, Indigenous artists hold responsibilities to their communities.

It’s a lot of pressure, in the first instance, to get a window of opportunity to express Māori worldviews in a gallery setting. Again, it’s a high-stakes performance environment that artists are asked to express themselves in. But realistically, these exhibition spaces are exclusive – what you bring to the table needs to not only sustain Western art audiences, but also serve the Indigenous communities that serve you.

Offering up Indigenous content exclusively to non-Indigenous audiences is not good enough anymore. If the work is not accessible or relevant to the Indigenous community that inspires it, it’s time to re-evaluate. Because profiting off Indigeneity, void of any commitment or service to community, is exploitation. We are all responsible to our Indigenous audiences, to make them feel safe and seen in foreign gallery institutions. But it’s also our responsibility to critique the systems of oppression and dismantle visual tools that have been created to destroy us.

Expectations of seriousness are perpetuated in art settings, but it doesn’t have to exclusively be that way. Ron Te Kawa is a shining beacon of how Māori artists can shape art infrastructure to serve and sooth Indigenous audiences with radical love, critical consideration, and care. It’s time for more Indigenous makers to offer audiences loud and rebellious native joy; every act of love counteracts the effects of a system that can feel stifling. Let’s do it for Indigenous art audiences, for our communities, for the future of Māori art.