Raukura Turei and Objectspace

Whakapapa is a Māori framework that places us within the world. It encompasses all relationships we experience and guides our knowledge and connection to whānau (family), hītori (history), tikanga (customs) and philosophies. In this presentation by Raukura Turei we are introduced to the whakapapa of her practice, and how the materials she uses in her work connects her both to her tīpuna (ancestors) and the whenua (land).

The materials I use in my artwork carry the whakapapa of my tīpuna (ancestors) and their connection with the whenua (land) of Tāmaki Makaurau. This connection spans many generations and traverses the east coast of Tikapa Moana to the rugged west coast of Te Tai Hau a Uru - Te Mānuka o Hoturoa.

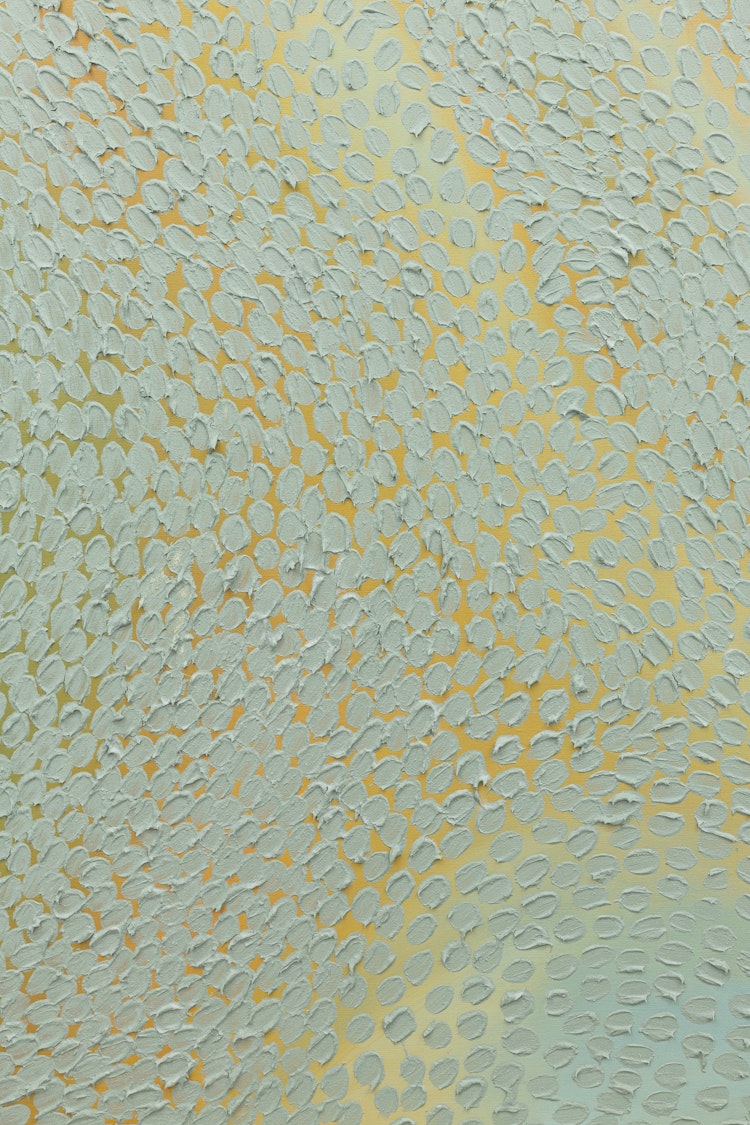

Aumoana is an iridescent blue aluvial clay that dries to a chalky blue grey. I collect this particular kere (clay) from the banks of the river Waimago, a tributary that runs into Tikapa Moana on the shores of the Hauraki Gulf. The mana whenua (people with authority) of this land is Ngāti Whanaunga, located specifically on the papakāinga (home) of the Royal whānau (family) who have been there for several generations. Te Ahukaramu Charles Royal recollects his kuia (grandmother) collecting the clay and applying it to her skin as a beauty mask.

The last time I collected aumoana from Waimango, I met with Charles to talk whakapapa and share histories of the whenua (land). After saying my karakia (prayer) to the atua of the taiao (gods of the natural world) I began my search, knee deep in the awa (river). It took a while traipsing through thick overgrowth to find the one known spot to dig for the kere (clay) and once the ochre clay was pushed aside to reveal the blue beneath it was evident that this particular source is a finite taonga (treasure) to be treasured.

I whakapapa to this whenua (land) through the occupation and intermarriage of my great-grandfather Te Hana Taua Turei and his parents who descend from Ngā Rauru Kītahi in Taranaki and were gifted land known as the Kawakawa Block after the Waikato-Taranaki Land wars. The Turei whānau (family) worked the whenua and intermarried with the mana whenua Ngāitai ki Tāmaki whose rich history predates the arrival of the Tainui Waka (canoe) and occupied vast areas of the east coast of Tāmaki Makaurau. The heart of Ngāitai ki Tāmaki is at Umupuia Marae (complex of buildings) on the shores of Maraetai. My tipuna (ancestors) are buried at the urupā (burial ground) at Matiatia on the Clevedon Coast and this was where my kuia, grandmother, Dorothy Turei grew up.

I didn’t grow up with my Kuia, my Dad’s mother, and he didn’t either. He went into foster care as a baby as a ward of the State, so didn’t grow up with his birth brothers and sisters, however they all lived in the suburb of Henderson, West Auckland in close proximity to each other. It was just before she passed away that he almost found her, just before I was born. She passed away prematurely in her sixties, fishing on the rocks at Te Henga [Bethells Beach]. There are fragments of her story from my Aunty who did grow up with her, and my cousins who knew her as children. Then there are also the Social Welfare files on her where the State agency back then went about writing case files that legitimised why they took Māori children off their mothers. There’s nothing positive in the case files. But it’s something.

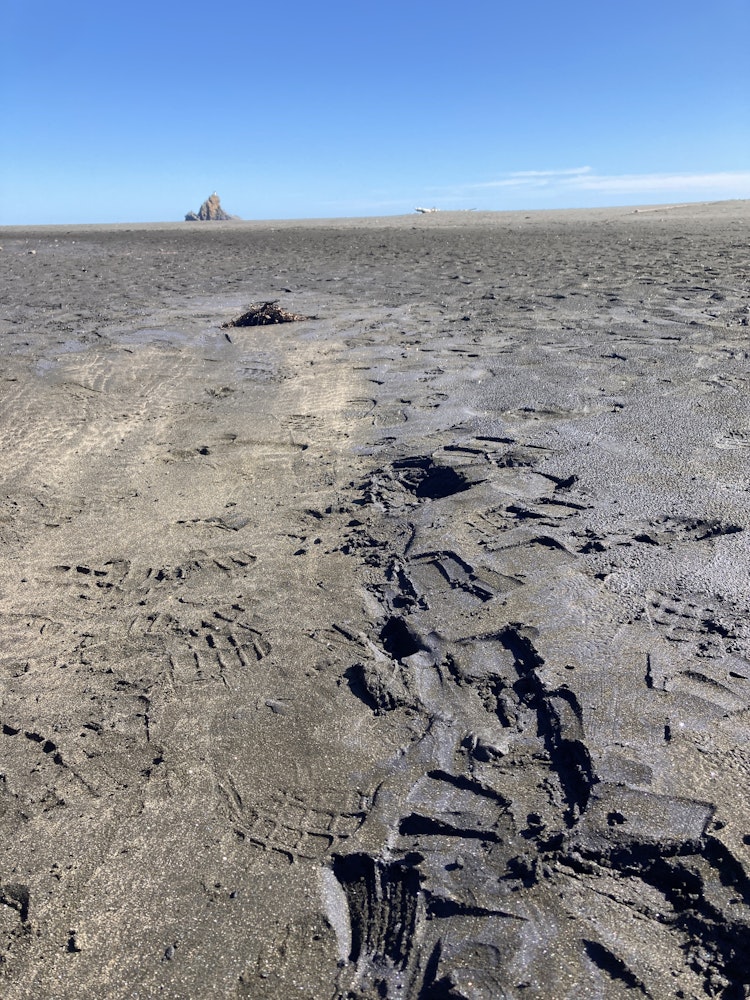

These fragments of stories are one side, but for me a more personal connection is that I feel her presence when I am at the West Coast. When I swim in the water, I feel this incredible sense of release of the unknown grief that I carry that comes out in lots of weird different ways. But there’s also an incredible sense of connection as well. So, collecting the onepū (sand) from there, was a way of finding a material means to connect to my grandmother’s presence on the earth, and have something enduring that is a representation of her and her strength. They’re dark, deep, black works that have a world of what can appear as sorrow, but within that darkness is a world of potential as well.

I collect the onepū, the black manganite sands of the West Coast, the children of Hine-oneone and Hine-tūakirikiri, to honour my Kuia. While she was prematurely taken by Hine-Moana, it is the ocean that connects me back to her. The ocean has the ability to strip away the generational trauma that has calcified itself between lost whakapapa and a stolen generation.

Ko te ngau a Hine-Moana

Ki a Hinetūakirikiri

He ngau mutunga kore

He ngau kukume iho

Ko tōku Kuia tērā

Hine-Moana gnaws away at the shore line. With every lap of her waves a greeting to Hinetūakirikiri and Hineoneone whose fine sands are slowly formed by this caress. The sea eats away at the whenua. The sturdy defender Rakahore of rock and stone eventually merges with Parawhenuamea of silt and sediment. These fine particles slowly build up again to form the body of Papatūānuku.

This constant ebb and flow is a ceaseless cycle, for centuries completely undisturbed, uninterrupted.