Dorothy Waetford, unless otherwise stated

Whakapapa is a Māori framework that places us within the world. It encompasses all relationships we experience and guides our knowledge and connection to whānau (family), hītori (history), tikanga (customs) and philosophies. In this presentation by artist Dorothy Waetford we are introduced to the whakapapa of her practice and how it is informed by her background as a dancer, and her local surroundings and whānau (family).

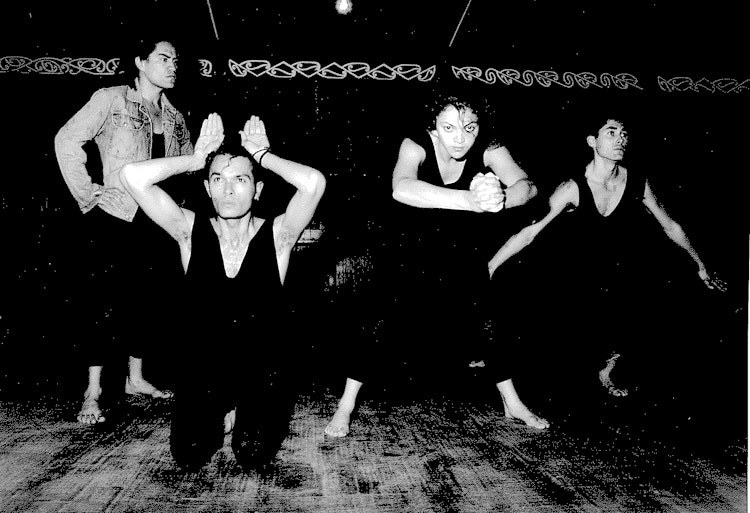

Based at Matapouri Bay, in Te Taitokerau, Dorothy Waetford is inspired by her local surroundings and whānau. Dorothy trained as a dancer initially, performing with Te Kanikani o Te Rangatahi and Taiao Māori Dance Theatre. She later pursued teacher training that led to an applied arts course, introducing Dorothy to Ngā Kaihanga Uku Māori Clay Workers Collective and Te Ātinga Contemporary Māori Visual Arts committee of Toi Māori Aotearoa. In recent years, she has focused her attention towards hapū art projects and iwi strategies for art and cultural development.

Ko Onekainga te maunga,

Ko Te Wairahi te awa,

Ko Ngāti Rehua, Te Whānau Whero me Ngāti Hine ngā hapū,

Ko Ngātiwai, Ngāpuhi-nui-tonu ngā iwi1

I trained with Te Kanikani o Te Rangatahi and Taiao Māori Dance Theatre during the 1980s learning to dance, perform and choreograph from some of New Zealand’s finest contemporary dancers. We toured extensively throughout the country and were mentored by many Māori and Pākehā performing artists and kaumatua (elders) who supported our endeavours to forge a new pathway using dance as a medium of expression to reflect our cultural worldview. I began dancing as a teenager continuing for ten years before moving north, to live at Matapouri on whenua whānau (family land) and raise my babies.

These years inform my creative practice as an artist using uku (clay) as a primary means to express the world I inhabit now.

I often group my works to observe the relationships between the ceramic sculptures. I’m interested in the interplay between light and shadow and the interaction of scale between works.

I live at Matapouri Bay, in Te Tai Tokerau, the northern region of Aotearoa. Living by the beach means the moana (ocean) and the movements of the natural environment heavily influence my mahi toi (art works).

Water surfaces, reflections, light and dark patterns and textures speak so much about the unseen world around us. I imagine that our tūpuna (ancestors) understood these tohu (signs) implicitly and integrated these understandings into waiata (song), kōrero (discussion), whakairo (carving), and raranga (weaving).

The beach influences my work but can also act as a collaborator. I sometimes utilise the natural environment around me as a source of inspiration for practical processes, taking fired pots to the beach to soften the rough textures using the natural movement of tumbling sand and wave action over the pots.

An important part of my process is using uku (clay) sourced locally to where I work, connecting with the life force in the uku. Processing clay can be tiresome without the right tools so you learn to innovate. For example, I use a fine sieve to filter out small stones, roots and coarser sediment from raw clay sourced from roadside clay banks to make clay slip.

Reusing and recycling clay to maintain a sustained practice is also important. In the image below you can see Muslin cloth bags filled with clay. Here I’m exploring using gravity to release excess water from the recycled clay.

At a Ngā Kaihanga Uku wānanga2, hosted by Māori artist, James Webster and ceramic artist Paul Lorimar at Driving Creek Railway and Pottery in Coromandel, we used locally sourced uku from the whenua (land) at Driving Creek. The colour of the clay was a rich terracotta. I loved the space we worked in, old sheds surrounded by bush warned by the natural light filtering in through the windows.

At this workshop in 2017, I completed a number of vessels from the locally sourced Driving Creek clay. The last image in the collage above shows a close up of the working edge of a vessel. We can also see the surface texture applied using a serrated kidney tool during the hand-building process with clay coils. I like to use metal kidneys with serrated edges to strengthen the clay walls both inside and outside when coiling, before paddling.

I worked on a collaborative work for the Sculpture in the Gardens exhibition, held at the Auckland Botanical Gardens. Our work Taiki e! United in Purpose! was created by myself and four other Indigenous clay artists, Rhonda Halliday, Alix Ashworth and Todd and Karuna Douglas.

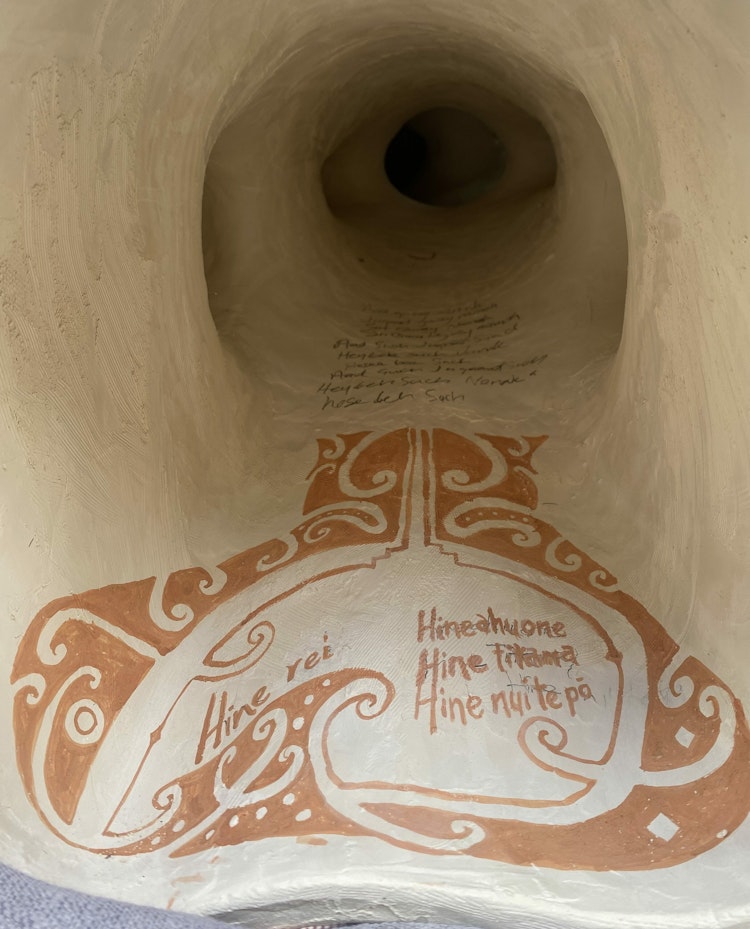

This image shows a view inside one of the pieces that was included as part of Taiki e! United in Purpose! A Karakia (prayer) is shown written inside the final works with pencil and kōkōwai (red ochre) painted free flowing, acknowledging ira wāhine (inherent female essence) narratives about uku (clay), uha (femininity), kurawaka (place name where the first woman was created) through ngā Hine rei, Hine-ahu-one, Hine-tītama and Hine-nui-te-pō (female deities).

E rū ana te whenua

E rū ana te whenua

E papā ana te whatitiri

Auē, auē, te wehi

Tēnei te reo whakatūpato ki te iwi katoa

Tāhurihuri mai ki te ao wairua

Haere, haere mai ki āhau

Composed by Te Moananui-a-Kiwa Anaru

The work, E rū ana te whenua (2011) was saggar-fired, which entailed a ceramic chamber constructed inside an electric kiln. The finished bisque work was placed inside the chamber along with combustible materials such as walnut shells, seashells, sawdust and seaweed before re-firing.

The figurative form was the starting point, the surrounding pieces were made by stretching the and rolling the clay into abstract forms and creating surface textures. At the time of making, Eyjafjallajökull erupted in Iceland causing major disruptions to air travel across Europe. This was a key turning point for the whole concept of the piece as an Uncle who passed away in Germany at the time was unable to be brought back home until the skies had cleared.

Included is a close up of the paper kiln firing held during Uku Aotearoa The Spirit of Materials workshops and demonstrations lead by Ngā Kaihanga Uku artists as part of a cultural exchange organised by ceramic artist and tutor Richard Rowland at Clatsop Community College, Astoria, Oregon, in May 2015.

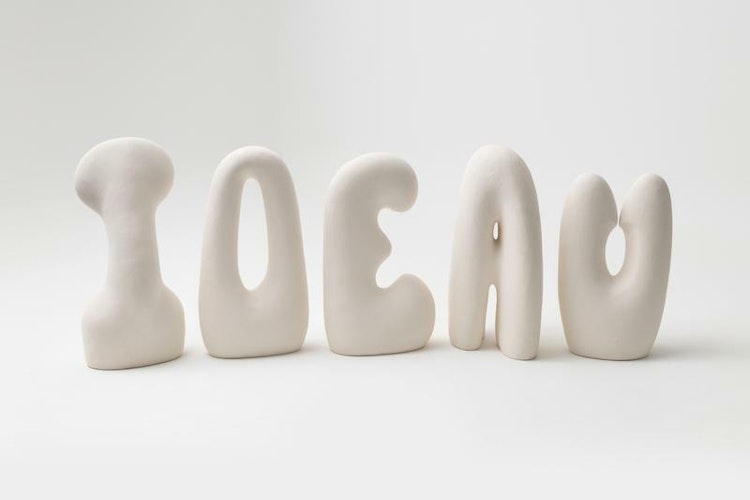

I had the opportunity to make this work, I O E A U during a house sit at ceramicists Greg Barron and Jin Ling’s homestead at Huanui, Whangārei, in 2016. I’d been playing with text on clay pots and exploring different figurative shapes and forms for years before making them. This series was inspired with the provocation: 'is the “natural” order AEIOU? or IOEAU?' When I think about what IO (supreme being) and AU (I, me) refer to in te reo Māori (Māori language) the sequence effectively shifts my fundamental worldview. The ways in which power is embedded within sound and the languages we hear and see over and over, begs the question, 'What will I teach my grandchildren and why?'

This series of figurative works is based on a particular feel and style that emerged during the Puhoro gathering of Indigenous artists at Tūrangawaewae marae in 2019.3 The inspiration came from the Waikato River, the kaikaranga4 at the daily raising and lowering of the Kingitanga flag.5

The title pays homage to a dance piece choreographed by Stephen Bradshaw and named by John Tahuparae. The uku (clay) came from the whenua (land) at the Auckland Botanical Gardens.

There are many thoughts and memories that influence my making while getting to know the limits of the clay. In my work there are gestural movements and body language influenced by watching my mokopuna (grandchildren); the influence of bodies of water like the Waikato river and coastal tidal movements; and the desire to find a surface that brings equanimity or cohesion to the piece.

Mentor to many, ceramicist Manos Nathan spoke about mileage – 'you’ve got to do the miles, do the hard yards', referring to the fact that there are no shortcuts on the learning curve – no one can teach you what experience can.

Ceramicist Colleen Waata Urlich referred to the words of Sir James Henare6 'kua tawhiti kē tō haerenga mai, kia kore e haere tonu; he tino nui rawa ō mahi, kia kore e mahi tonu' – 'you have come to far not to go further; you have done too much, not to do more'

What else needs to be said other than keep going, keep making, keep your eye on the horizon where the light rises and returns.