Jessica Hemmings

Jessica Hemmings reflects on the textile works of artist Toril Johannessen and her exhibition Unlearning Optical Illusions. At first sight, Johannessen’s works evoke connotations to the patterns found on West-African textiles but at a closer look, these patterns explore and challenges early theories on optical illusions.

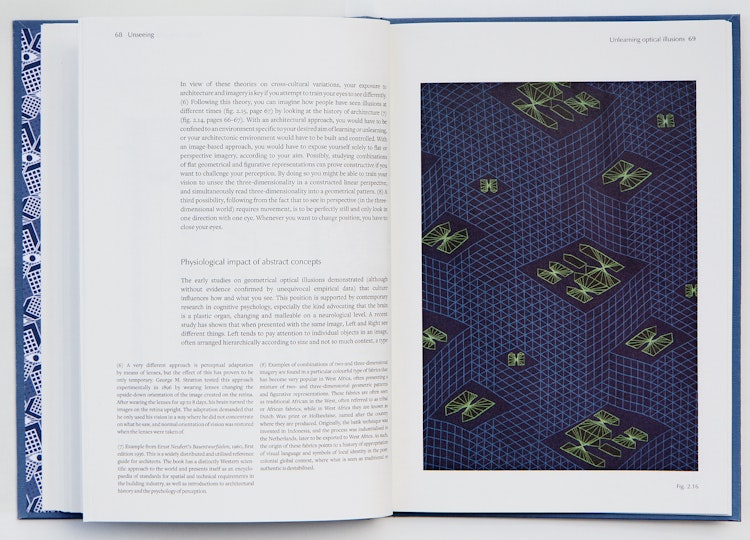

Unlearning Optical Illusions is Toril Johannessen’s iterative reflection on textile manufacturing. Not that this is where she began in 2013 when the first stage of the project emerged as a chapter in her publication Unseeing, a two-part book published by the Hordaland Art Centre’s Dublett artist book series. But it is where the project has taken her. Seven optical theories – Oppel-Kundt, Hering, Wundt, Hermann, Müller-Lyer, Zöllner and Poggendorf – provided inspiration for a series of printed textiles that first appear on the pages of Unseeing alongside writing that patiently unpacks much of the dubious science that has historically explained sight. But while the interplay of science and culture has regularly found its way into Johannessen’s practice, for the Unlearning Optical Illusions project the science of sight is really about culture.

In the preface to Unseeing Johannessen explains, ‘This book is about world views and the possibility of perceiving differently, visually and cognitively.’ Information previously held as fact is questioned, but alternative cultural connections are also suggested. For example, Johannessen acknowledges, ‘Although contradictory, what most of the early theories for geometrical optical illusions held in common belief was that how you see an illusion is due to differences in interpretation, meaning that what you see is a result of what you can recognize and of your expectations; meaning that how you see is dependent on what you already know.’

The spectre of racism runs through many of these early optical theories. For example, Johannessen recounts that the carpentered world theory would explain that differences in perception of the Müller-Lyer illusion are based on ‘test subjects [who] lived in a world with few straight angles and predominantly round buildings… [compared to] architectural environments largely dominated by rectilinear shapes.’ Johannessen is frank about the tensions to be found in many of these theories. She cites on the one hand that recent experiments on animals have objectively proven that ‘the visual environment modulates visual cognition’ while acknowledging that the earlier research she refers to for this project sought to find culturally and sometimes racially determined factors for differences in perception. ‘Some of the experiments and theories on cultural variation in perception easily lent themselves to ideas about the superiority of Western man, as if variation in perception were evidence of differences between ‘primitive’ and ‘modern’ minds.’

Each of the seven textile designs Johannessen developed refer, in part, to the Dutch wax resist textiles – a tradition not without its own convoluted history: during Dutch colonization of what is present day Indonesia the Netherlands began to manufacture wax resist textiles for resale back to the local market. A combination of poor quality and taxation was likely responsible for this failed business attempt. But long before the Suez Canal opened, Dutch – and British – ships stopped along the coast of west Africa before rounding the treacherous Cape of Good Hope and heading east to the Spice Islands. The cloth was instead traded during these refueling stops. Much later, as west and central African countries began to gain their independence the cloth was adopted by many national dress traditions of the region – a colonial import now celebrated as post-independence national dress.

In 2014 Johannessen exhibited the textile designs as seven large-scale photographs of the digitally printed cloth in the Paradise Reclaimed exhibition at Festspillutstillingen in Harstad. In this second iteration of the project viewers are guided along dotted vinyl lines on the gallery floor with instructions to close one eye while changing their viewing distance in front of each framed work. Here the textile is pure, albeit ever changing, pattern; the flat printed cloth creased and folded to distort the repeating imagery and test our periphery vision.

For Unlearning Optical Illusions (III) a small production run of the cloth was manufactured in Ghana. From the flat, framed photographs early in the series, the cloth began to make an appearance as lengths and bolts of textiles in the gallery. Tables holding cloth that the public were invited to touch were included in the Migrations exhibition I curated in 2015-2016; while steel racks held unspooling lengths suspended from the ceiling at the Vigeland Museum as part of the exhibition Kunsten tilhører dem som ser den, Norsk Skulpturbiennale in 2015.

Uncut cloth is in keeping with many of the west and central African dress traditions that, unlike our own, keep lengths of cloth intact. Wrapped around the body, uncut cloth easily adjusts to accommodate changes in size – and for women pregnancy – without requiring a new garment. More recently, at the Kabuso Centre east of Bergen the same cloth has swooped and billowed again in lengths draped from the gallery ceiling. Arguably this installation represents the most resolved presentation – of a notoriously difficult format to exhibit – from the Unlearning Optical Illusions series to date.

The versions of Unlearning Optical Illusions now also read as an exercise in textile exhibition strategies. Total control was initially exerted on the photographed cloth: folded, framed and held behind glass the material had no chance but to behave. As further versions of the project have emerged the cloth has been allowed to behave more like itself – billowing and creasing – with less control exerted on its right angles and more attention given to its movement and misbehavior. At the Kabuso Centre, for example, the bolt closest to the door of the long narrow gallery space had lost its starched, straight body – either through too many surreptitious hands tempted to reach out and touch or one of countless other unknowns in the production process – a lighter quality material perhaps. But this is what cloth does. Presenting it otherwise makes it something other than cloth.

Working with the Oslo-based fashion designers HAiK, a wearable collection using the printed cloth has now been designed which will also be manufactured in Ghana. Rather than design from Oslo for production far away, HAiK took the step of starting to design the collection once on the ground in Ghana – a recipe intended to ensure that they responded to their local environment rather than apply a distant assumption or stereotype of their idea of place. The collection brings together fabric sourced locally alongside the Unlearning Optical Illusions prints with garment shapes that refer to the sport clothing they found so visible during their visits.

With a garment collection underway, Unlearning Optical Illusions has neared the completion of its journey. Printed pages where fashion typically concludes its production cycle became, for this project, a starting point. Sourcing a small production run in Ghana followed, and now a fashion collection with HAiK brings the printed textile designs through to the very different conclusion of an otherwise familiar cycle: design published before printed; informed and manufactured in Ghana; soon for sale in Oslo.