André Gali

Torbjørn Kvasbø defines himself as an abstract expressionist and is known for burning his monumental sculptures in the large, woodburning kiln in his backyard. In this interview by André Gali, we learn about Torbjørn Kvasbø’s road to ceramics and how exhibiting, networking, and teaching, across three continents, has contributed to his standing as one of the world’s leading ceramic artists.

It has been said about ceramic artist Peter Voulkos that ‘had America, as they do in Japan, a system of selecting the country’s most precious artists to be called “Living Treasures”, Peter Voulkos would indeed be one.’ A similar statement could easily be made about Norway and Torbjørn Kvasbø.

Kvasbø travels regularly to different parts of the world to participate in exhibitions, biennales and symposiums. He has led numerous workshops in the US and elsewhere, and been a ceramics professor at the Academy of Design and Crafts in Gothenburg, and at the University College of Arts, Crafts and Design in Stockholm. As a professor, he was active in school politics and considers education to be one of the most important areas where information and experience about ceramics are shared; therefore, he believes all artists should be involved in education.

‘As a practising and professional artist, it is important to share your experiences with students. The transference of knowledge is one important aspect, but sharing networks with the students is equally important; not just for the students, but for those of us who work as professional artists, because it gives insights into what is going on. A lot of interesting art is made in the art schools,’ he explains.

Kvasbø was a professor for twelve years and actively engaged in renewing and restructuring the art schools where he taught. After managing the ceramics department at the University College of Arts, Crafts and Design in Stockholm, he decided to spend more time in his workshop, but still is passionate about how art schools are run and how art is taught.

From the piano to clay

As a youth, Kvasbø didn’t intend to be a ceramic artist. His hometown of Kongsvinger, approximately 70 miles outside of Oslo, lacked a wealth of cultural activities; but his father, author Alf Kvasbø, wanted his children to have musical education. And, for a long time, Kvasbø expected to become a professional pianist:

‘I started playing the piano as a seven-year-old. And at age 20, I had become a very good pianist,’ he recalls.

‘I applied to get into the Norwegian Academy of Music in Oslo after graduating from college, but since the competition amongst piano players was stiff, I didn’t get in.’

What to do? As Kvasbø tells it, he felt if he just rehearsed diligently for another year, he could apply again and succeed:

‘At the time I felt the need to move out of my parents’ house. After all, I was too old to stay home, and I couldn’t just rehearse —I needed something to do. So, I applied for the Arts and Crafts Department at Røros Technical School. The school had a piano, and my idea was to study a bit and rehearse a lot.’

At the school the students worked in wood, metal, and ceramics. But Kvasbø gradually immersed himself in the clay and, forgetting to practice the piano, eventually decided to seek admission to schools for applied art — both in Oslo and in Bergen.

‘Thank God I didn’t get into the school in Oslo. I think that would have ruined my career,’ he states, referring to the educational system there at the time. In retrospect, Kvasbø thinks the teachers in Oslo were too concerned about being artists, and were not focused enough on skill.

In Bergen, where he began studying in 1975, the education was different.

‘In many ways it was an old-fashioned school since the focus was on handicraft and skill. And the material as a medium, or a language for expressing yourself, was very important. The school was inspired by English traditions for ceramics and crafts, where the thoughts of Shōji Hamada and Bernard Leach were held in high esteem. The choice of material was essential for how you developed a language as an artist.’

A workshop of his own

So why did Kvasbø choose to work in clay?

‘It was a mere coincidence … I might as well have chosen printing, which also intrigued me. The process and the way the prints went through a transformation inspired me. As I started my studies in Bergen, I was very much in doubt whether to choose printing or ceramics.’

He chose ceramics and started working with handicraft, tableware, and useful products for everyday life. Working in the school’s workshop from seven in the morning to late at night, he experimented with the material, the burning process, and different glazing techniques — and he was in good company. In his class were hardworking ceramicists, and several of his classmates are still among the most important Norwegian ceramic artists today:

‘Harald Solberg, who now runs the art centre Bomuldsfabriken in Arendal, was one of my classmates, and Marit Tingleff, Hanne Heuch, and Elisa Helland-Hansen; the elite division of Norwegian ceramicists,’ he remembers.1

For three years, Kvasbø studied in Bergen, and during that time also developed a workshop with a large woodburning kiln at his grandfather’s place in Venabygd — a rural area approximately 130 miles from Oslo.

‘The last half year before my graduation I worked here. Then I filled my car with what I had made for the graduation show and drove across the mountains to Bergen.’

After graduating he left Bergen to come and live in Venabygd with his wife. He never wants to move back to Bergen, even though the school has tried to recruit him. But he still feels that the ceramics programme at the Bergen school is an important institution:

‘Bergen Academy of Art and Design2 is among the finest schools in Europe. In my time as a ceramic professor, I have visited lots of art schools and seen a lot of graduation shows. And Bergen Academy of Art and Design and the University College of Arts, Crafts and Design in Stockholm hold high standards. I still work as an external examiner at Royal College of Art in London – possibly the best school for arts and crafts in the world – and I can tell you that Nordic and Scandinavian artists are doing well.’

Working hard

To build a career, but also for mere sake of survival, Kvasbø started showing his works around the country and selling them directly from his workshop.

‘I’ve exhibited almost everywhere in Norway - in the smallest, most obscure places. That was the only way to survive financially as an artist, and gain recognition. At the same time, I gained a lot of valuable experience,’ he recalls.

Gradually he started receiving invitations to participate in bigger shows and more important exhibitions. He exhibited early on at the National Museum of Decorative Arts and Design in Trondheim3 and in Kunstnerforbundet – both considered to be among the most important exhibition venues in Norway.

‘It took a lot of work. You had to work hard to survive. And I got a lot of support from the locals — they bought my handicraft, and the local newspapers covered my shows, and they still do, because they understand that I work hard to do what I do.’

He feels the local community has a lot of respect for his work even though the neighbours consider being an artist something rather strange. Part of the reason for this is that Kvasbø has built an impressive international career. But it took a lot of time, and he worked hard for it.

‘Slowly I came in contact with international ceramic artists and they started inviting me to do workshops. It happened partly by accident, and partly because when you work very hard for something, it eventually happens,’ — he explains.

‘I was experimenting with different natural kilns and developed different techniques, and word got around. So, when foreign ceramicists came to visit the art academies and hold lectures and so on, my Norwegian colleagues brought them around to my workshop to show them what was going on here. Eventually I developed a small international network that wanted me to demonstrate my work processes for other colleagues.’

A Norwegian ceramicist in America

Kvasbø began receiving invitations from art schools, especially in the US, to come and hold lectures and workshops. Between 1987 and 2001, he reckons he visited approximately 50 schools in North America.

‘Sometimes I visited the US as much as five times a year. I organised these tours so I could visit several schools at a time; travelling around the continent with workshops, showing my techniques, and sharing my knowledge and experiences with fellow ceramicists,’ he recalls.

‘The ceramic milieu is unique in this respect. Because it is such a complex and complicated field, you have to share information and techniques with each other - and the generosity is overwhelming. I think this distinguishes ceramics from other artistic fields.’

In America, he attended the annual ceramics conference called NCECA [the National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts], where 5-6,000 ceramic artists from around the world gather to exchange experiences and knowledge, and to show their works.

‘This was a great opportunity to develop an international network — everybody of importance in the field was there,’ he explains.

In the US, ceramics as an art form holds a high position, and Kvasbø connects this to the Abstract Expressionism in ceramics that developed in the 1940s, through the works of Peter Voulkos, Jim Leedy and Ken Ferguson, to name but a few artists.

‘Almost all the artists who have been important in American ceramics have also been professors.’ This helps explain why Abstract Expressionism exercises enormous influence and has been an important paradigm for several generations of American ceramicists.

Kvasbø admits that he considers his own work to belong to the realm of Abstract Expressionism:

‘Peter Voulkos and his generation have been important inspirations to my own work. The way they use the material has had a huge impact on my development.’

From Asia to Oslo

Throughout the last decade or so, Kvasbø has also exhibited in Asia. Starting in Australia and New Zealand, he then showed his work in Korea, China, and Taiwan. He received much recognition as the one-man jury for The Fletcher Challenge Ceramics Award exhibition in 1996 (the last year the exhibition was held):

‘Jurying that exhibition, which is prestigious, helped me gain recognition in Asia, I think. Even though I had participated in several exhibitions and won many prizes there, I now became more known in the ceramics community in Asia.’

As a professor at the University College of Arts, Crafts and Design in Stockholm, he developed an exchange program where he went to teach at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, and a professor from Beijing came to Stockholm. This also helped build his reputation in Asia.

Furthermore, since the Asian countries seem to compete with each other in terms of being the best place to show art, he continuously gets invitations to biennales in Korea, China, and Taiwan.

‘Japan has traditionally held a high position in ceramics exhibitions in Asia, but lately Korea has been challenging that position. Now China and Taiwan follow suit. These are countries that spend enormous sums on art festivals, and they have the best curators,’ he explains.

Earlier this year, Torbjørn Kvasbø’s ceramic works could be seen in the Taiwan Ceramics Biennale at Yingge Ceramics Museum, and at Collect, the international fair for contemporary objects at Saatchi Gallery in London. In September, his works were part of the Le Cru et Le Cuit exhibition at Galerie Favardin & de Verneuil in Paris.

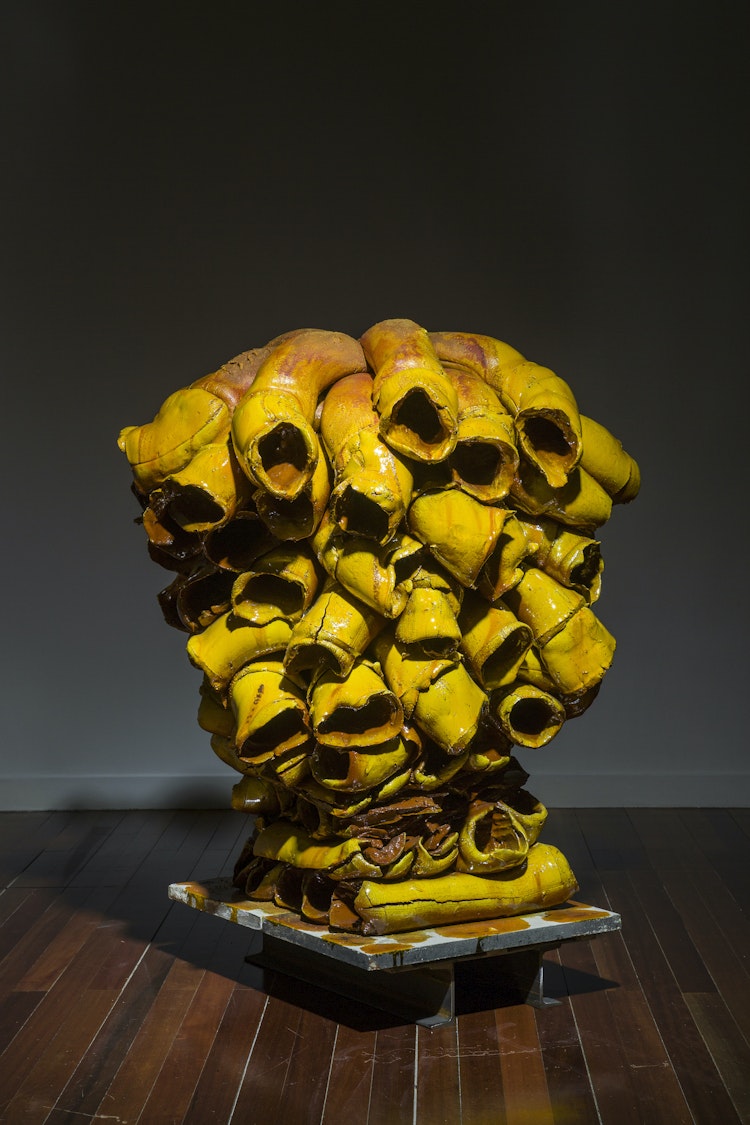

At the moment, he is working on a series of abstract sculptures where the clay has been moulded through an extruder, a mechanical device that makes sausage-like lumps of clay. These lumps Kvasbø then carefully shapes and puts on top of each other. The sculptures have a slight resemblance to torsos or vessels, but Kvasbø himself is mainly concerned with the energy they express. In October, these works will be on display at Kunstnerforbundet in Oslo.