Monica Holmen

Nanna Melland is known for making jewellery with unorthodox materials. In this interview by Monica Holmen we are introduced to her practice which spans from personal jewellery to public installations.

Swarm adorns the reception area on the library’s main floor. Towering several metres over floor level, it is a white wall covered by thousands of airplanes cut out of aluminium; these come in seven sizes and are pinned to the wall. Every relation to jewellery seems absent — until you discover that in exchange for a small fee, you can remove one of the airplanes from its pin and wear it as a piece of jewellery. So what is this? Jewellery or installation?

‘I’ve made a choice — I call it an installation,’ says Melland.

Her move away from the world of miniatures and jewellery, to the world of installations, can be seen as a form of anti-categorisation; but also as a more conceptual attitude to her artistic practice, regardless of whether it concerns jewellery or installations. At the same time, she admits that by allowing the public to take a piece of the installation and wear it, the work moves into the sphere of ‘wearable jewellery.’

School

That categories are open-ended is an idea Melland acquired while in school. She studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, under Otto Künzli, a professor internationally known for his intellectual approach to the medium of jewellery.

‘I had a fantastic education,’ Melland smiles, and adds:

‘It was unique. Only in Munich can you study jewellery with the same open structures as other art academy disciplines. In contrast to other types of education, we had time; there were no texts we were required to read, nor were there exams. The only formality was a diploma at the end of the course.’

With the intellectual approach to art jewellery and the ‘loose’ structure of her education, one might suppose her art represents a different view of artistic practice, and a ditto attitude to distinguishing between visual art, craft-based art and jewellery. Melland reflects a bit before answering:

‘The distance is often great between craft-based art and jewellery, and the latter finds itself in perhaps an even worse corner — one called “decoration”. What’s been exciting in Munich, is that because of the bombing of the school during World War II, it temporarily moved into the Fine Art Academy. Since then, there have been three strong professors in jewellery, and in that time frame, the jewellery department has built a good reputation and achieved respect amongst colleagues working in the visual arts.’ Melland elaborates:

‘I think the good reputation is due to an understanding of what art is. We didn’t really discuss the extent to which something is craft-based art or fine art. Instead, what was interesting and challenging was whether you could capture someone’s eye in an exhibition. And that’s what is different about Munich: people are not focused on this categorization discussion, but on what they see on the table in front of them. But the format of jewellery is small, and today there’s a tendency to think that “larger is better”. But it’s difficult for a ring to compete with a large installation in a 500 square metre room,’ Melland admits.

Taking this problem into consideration was something she and her fellow students learned to do in Munich:

‘A large part of our time in school was used to present our jewellery in group exhibitions. This experience has proved useful after graduation. It certainly helped me to stand on my own two feet, to be a professional artist.’

Hang it on the body

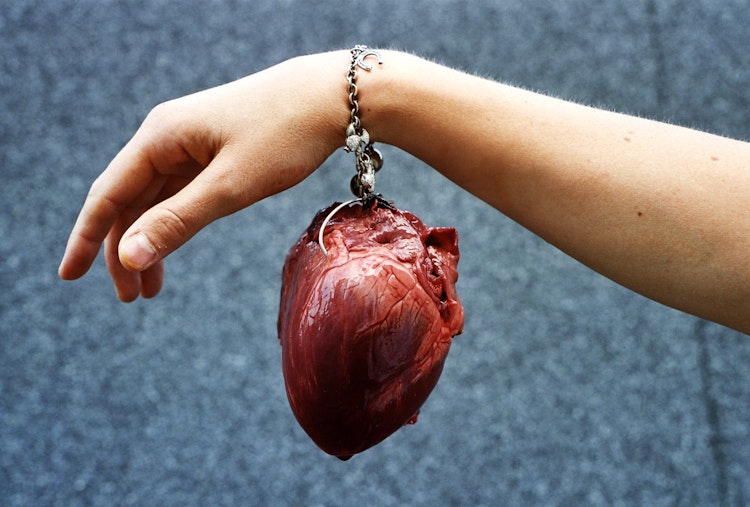

Melland began making jewellery with (among other things) pig hearts and used intrauterine devices. She has explored a range of materials and, at least as far as size, form, and weight are concerned, her jewellery pieces may seem impossible to wear. But this is not the case:

‘The definition of a piece of jewellery is that you can hang it on the body. The extent to which someone wants to hang one of my jewellery pieces on his or her body – this question isn’t all that important for me, but it’s important that the works can be worn. If they can’t be hung on the body, I would be making pictures.’

Melland asserts that what is special about jewellery is bodily contact —but this aspect does not extend to all jewellery:

‘Jewellery history shows that many pieces have been made with the express goal of not being used, examples being certain crown jewels and ritual jewellery. Several of my pieces enter this ritual landscape. When picking them up and touching them, I think many people will recognise that they don’t actually want to wear them…’

And Melland has experienced people’s reactions to her sometimes unconventional choice of materials:

‘I have, for instance, made a series of necklaces out of lead, called Les Fleurs du Mal (‘The Flowers of Evil’). The reaction – and it came mostly from my colleagues – was that I couldn’t do it because it wasn’t wearable.’

A weird reaction from a group of artists, Melland thinks.

‘If there’s something you shouldn’t or can’t do, then it is precisely within the context of art that you should do it! But clearly, lead is poisonous and requires that the person who chooses to wear the necklace must be aware of the material’s poisonous nature. To avoid direct danger, I lacquered and sealed the lead pieces so they could be worn.’

The fact that lead is not a traditional material for jewellery does not concern Melland:

‘In our autonomous art world and avant-garde jewellery world, I found a taboo about lead —and I like that.’

The unorthodox material choices are not random, and Melland experiments with several materials before making a selection.

‘When I choose lead, it’s not because I haven’t tested out silver and gold and other materials. Lead has fantastic qualities — it’s like butter, very soft. The colour is unbeatable if you’re aiming for a gloomy expression. The material’s weight is unparalleled. And you can get hold of it easily – literally by the bucket.’

Les Fleurs du Mal are casts of orchids. This was the first time she used lead:

‘I wanted the pliability lead could offer. Had I used another metal, the results would have been stiff. Lead allows the flowers to live, but silver would have rendered them hard and pointy.’

Melland made another discovery while working with lead:

‘It’s as if we’re predisposed to perceive some things as beautiful and other things as ugly; and because lead is poisonous, it’s easy to perceive it as an ugly material. So to discover the beauty of lead was a positive surprise, and I was able to confront my own prejudice.’

The opposite of lead seems to be gold. Melland initially trained as a goldsmith, with the ambition of working with gold. Hence, when working with lead, a tension surfaces — both in terms of material and craft.

New material, more conceptual

To make Swarm, Melland has used a material far different from lead:

‘Aluminium is a new material for me. It’s highly versatile, being used in everything from Boeing airplanes to aluminium foil.’

The choice, however, was not a foregone conclusion, because she tested several materials:

‘I chose aluminium because of its formal qualities: how it captures light, how thin it can be before it breaks. I wanted something light, almost not even there, that could “fly”. Aluminium has all these qualities.’

So, there is also a relation between the material and the work’s content. Compared with earlier works, Swarm is far more conceptual.

‘This is pure mass-production. It’s almost a pure industrial production. I’ve had a hand in everything, but with 10,000 miniature airplanes, it’s no longer a matter of craftsmanship.’

The airplane motif stems from global air traffic, with air corridors choked with airplanes – this, for Melland, constitutes a flying swarm of humanity.

‘I have, for many years, been interested in symbols, rituals, people, language, and communication. So to choose the airplane motif isn’t just about the theme of global air traffic. It’s also about a very old symbol that floats, as it were, between different contexts. Flying is a corollary to human existence; through birds, through the longing for freedom, and now today it’s part of everyday life. The airplane can be understood as a universal symbol. Universal themes are exciting because they have to do with human existence.’

Jewellery as archaeological objects

Some of Melland’s earlier works have been called feminist. The necklace 687 Years, for which she won the prestigious Kunsthåndverkprisen1, consists of numerous galvanised and used intrauterine devices (IUDs). Like Swarm, the necklace also addresses universal themes:

‘I am not that concerned with feminist issues. The practice of controlling fertility is broader than that; it has been around since time immemorial, and it’s something both men and women have been concerned about. Contraception is a private issue, but also of great public concern, and it has also always been a political tool. The IUD is mass-produced in many places in the world and is situated in a context teeming with politics and economic interests.’

Here the social anthropologist in her comes out:

‘This little object represents a chapter in the history of humanity. The IUD will become an archaeological object; in 1,000 years, archaeologists will find it in the skeletons they dig out of the ground. I think this is a fascinating theme. Something similar could be said for the airplane – it offers so many approaches to thinking about our existence.’

The IUD was not chosen simply because it was a symbol, as was the case for the airplane, but also because it was an object placed inside the body. Melland used real IUDs to make 687 Years: ‘I wanted to use IUDs that had been inside bodies. The title represents the collective amount of time they were in use,’ she explains, and continues,

‘Their form is important, but so also their history — that they have been inside bodies. When I was first given them, they were caked with blood and quite disgusting. So my solution was to galvanise them, that is, to seal them inside a sheath of copper. Their history is now hidden, sealed inside the copper form. In this sense, the work also functions as archaeological material. The jewellery piece is something more; you can’t just hang this around your neck.’

The masses and the individual

There is less history in Swarm than in 687 Years, but the idea is that Swarm’s history is yet to come — when people take the small airplanes out into the world.

‘I’m in the process of making a website which will allow people to follow the various exhibition venues. Eventually people will send me photos of themselves with the airplanes. That people wear them is important.’

In this way, she hopes to emphasise individuals in the flying mass of humanity. For just as with the IUDs in 687 Years, Swarm’s airplanes represent a theme running throughout Melland’s artistic practice: the masses and the individual. Even though Swarm is more conceptual than her earlier works, the theme links her oeuvre together:

‘For me, the craftsmanship and formal qualities are just parts of the artistic process. My starting point is always an engagement in a social issue, a theme that grabs me.’

Especially for Swarm, the idea about the masses and the individual is the key. A swarm is a mass of something moving, and for Melland, it is beautiful and fascinating, but also sinister:

‘A swarm has seductive symmetry, but once inside it, you lose your individual identity. This strikes a chord in me, which I think resonates with more general existential anxiety – the fear of ceasing to be an individual.’

She shares her thoughts on existentiality:

‘My life as an individual in this world is of primary importance to me. But if I step back to gain a wider perspective, I see that I’m part of a culture, a trend, an art historical project. Moving even farther back, the individuals around me disappear and the masses come into view. The ambivalence of this is something I find interesting. But in each and every swarm there is an “undetonated bomb”, also in the swarm of humanity. There is a kind of social contract in a group —but it only takes one bomb, or one false step, for hell to break loose. The vulnerability is always there, but easy to forget.’

That is also how it is with air traffic:

‘Everything is so normal; we forget the super-existential, surreal experience we’re in. We’re flying, and the whole infrastructure on this actually works. But then an Icelandic volcano erupts, and we’re suddenly overwhelmed with vulnerability. Suddenly no airplane can land in any country in the northern hemisphere. Complete chaos reigns.’

‘As an individual you can suddenly be swallowed by the masses and disappear, but at the same time you have an incredibly important position — because each individual helps create the great symmetrical scheme.’

Relational jewellery

After the show at Deichmanske Public Library in Oslo, Swarm will travel to several other locations including Schmuck 2013, a large jewellery fair in Munich, and then to The Gallery of Art in Legnica, Poland. But how do the different contexts affect the installation’s relational aspect? In a gallery setting, visitors are unaccustomed to taking anything away from an artwork, whereas at a fair, visitors expect to be given a number of things for free, even though those things are seldom art. And what about the public library setting?

‘Things are rolling along,’ says Melland.

As she points out, the work poses a challenge to people who have come to borrow a book for free. The smallest airplanes can be had for 50 kroner.

‘That’s an affordable price for most people,’ she thinks, ‘but you can’t guarantee that people have 50 kroner in their pocket when visiting the library. The most important thing is that people have the opportunity to participate in the work, but also that they can freely choose not to participate. I want duality in my works,’ she stresses.

‘When people acquire these airplanes, the work starts to move – it starts fluctuating. When people wear an airplane, they become part of the installation.’

As an individual you can suddenly be swallowed by the masses and disappear, but at the same time you have an incredibly important position — because each individual helps create the great symmetrical scheme.

Outside the comfort zone

Swarm is the first project Melland has done for a public setting, and it goes without saying that it is very different than working with jewellery.

‘Oslo’s public library is not just any public space; it’s a heritage site. I wanted to put the installation there because it is frequented by the masses,’ she confides.

It took quite some time to mount the thousands of airplanes, and for security reasons she was unable to work after closing hours:

‘Instead, I stood there every day from morning to evening, beginning just after New Year’s, 12 hours a day for two weeks.’

So the isolation of the studio was gone.

‘You’re out of your skin, out of your comfort zone; but it’s interesting to find that I like it and can handle it.’

Melland worked in the library’s reception area, a place with a continuous flow of people wanting to borrow books.

‘The advantage is that this is a natural place for people to come to take a break and ask questions.’

And many good conversations have arisen:

‘The public didn’t distance themselves. People returned to talk more with me, and there were many fruitful conversations. You don’t have to be a scholar to say something wise – that’s something I’ve experienced here.’

So the question is: is Melland satisfied with the result — with the way the work has turned out?

‘I had planned on working with a smaller wall, but then I thought I should just go all out since I would probably never again have the opportunity to work in such a large format. To stand like a tiny creature in front of this huge wall – that was the feeling I was looking for. Standing at the workbench in my studio, my focus is entirely different. There I’m always working in miniature. With Swarm I entered into chaos, lost control, and remained there. I built a symmetry which was then destroyed. If there’s only symmetry, it’s boring; and if there’s only chaos, then there’s only chaos.’