Mariann Enge

Arlyne Moi

Under the term ‘composite ceramics’, artist Jens Erland combines mechanical elements, performance, and industrial materials into ceramic sculptures and objects. In this interview by Mariann Enge we’re introduced to his work, and how coincidence and growing up close to agricultural industry shaped his path to ceramic art.

‘The relationship between human beings and machines has been my main

focus for the last fifteen years,’ says Jens Erland, one of five

Norwegians participating in the sixth Gyeonggi International Ceramix

Biennale in Korea.

Jens Erland (b. 1945) is a doyen of Norwegian ceramic art, yet also one of the most innovative ceramicists in the country today. He began his artistic practice in the 1970s, but it was not until the ‘90s that he gained the wider art world’s attention. This was when he gave up working in a Japanese-inspired way, and started experimenting with combinations of ceramic and industrial materials. These works he describes as ‘composite ceramics.’

The relationship between human beings and machines has been my main focus for the last fifteen years

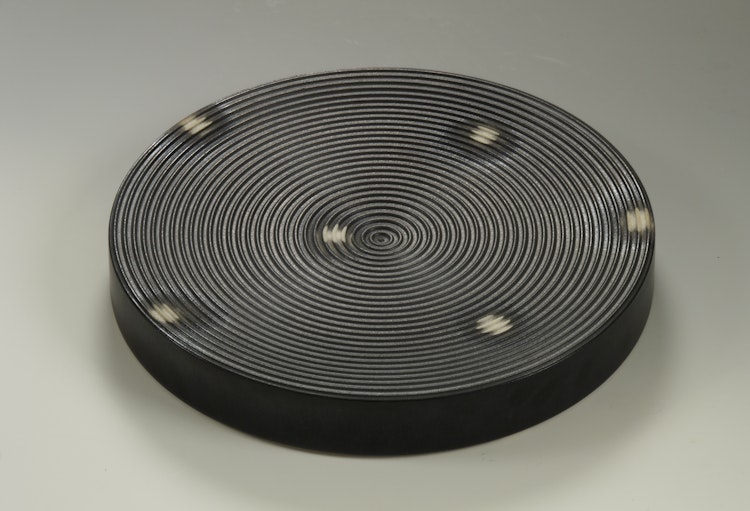

While participating in the ongoing travelling exhibition Paradigm,1 Erland is also one of five Norwegians whose works are included in an international juried exhibition in Korea this year: the sixth Gyeonggi International Ceramix Biennale. This is the third time Erland’s works have been showcased in Korea; he participated in the first Korean biennial in 2001, then again in 2005. The results of his first experiments with industrial materials are included in the series Circular Dish (1995-96), and a later addition to this series, a work from 2000, won the ‘Special Prize’ in 2001. Erland travelled to the biennial to receive his award, and recalls how impressed he was over the Korean initiative.

‘In 2001, perhaps as part of their long-standing rivalry with the Japanese, the Koreans invested enormously in contemporary ceramics. They spent the equivalent of one billion Norwegian kroner in building up three ceramics centres – in the so-called ‘ceramic belt’ – southeast of Seoul. The Korean president officially opened the first biennial, and the organisers were able to induce some of the world’s best ceramic artists to hold workshops in connection with the event. The organisers’ initial ambition was to create one of the world’s most important meeting places for ceramicists. In addition to presenting contemporary works, they arranged historical and thematic exhibitions, and loaned in works from across the world. All the exhibitions were accompanied by high-quality catalogues,’ says Jens Erland.

Circle to Korea

Erland confides that this year, at the sixth Korean biennial, he is exhibiting the work Circle II – a relatively large and thin wall object, 230 cm in diameter and 2,5 cm thick. It consists of pieces of a ceramic ring that was made during a performance held at his last solo exhibition entitled CIRCLE

(performed at Skur 2 Gallery in Stavanger, 2010). During the performance, Erland lay on a bed suspended from the ceiling, over a large rotating ‘pottery wheel’ upon which was placed a5 cm-wide outer circle of clay. With a piece of industrial rubber attached to a stick, he scratched a centre line in the clay. During the drying process, the ring cracked into several pieces. These he then slipped, fired, and mounted on an aluminium ring.

Before the exhibition opening, Erland had created two similar works in black and white, Circle I and Circle II, and had mounted them on the gallery walls. The equipment – including the bed and the large mechanical wheel – formed a key part of the exhibition. They are still important, Erland stresses, as reminders and traces of the exhibition and the performance, which is documented with the video Circle, by the photographic artist Geir Egil Bergjord. This video will be on show in Norwegian Craft 2011, this year’s edition of the Norwegian Association for Arts and Crafts’ annual juried exhibition.

‘The motif is the wobbly yet precise groove that emerges when I am suspended from the ceiling and lying on the bed, while the wheel turns,’ Erland explains. ‘The expression is marked by mechanics and human presence, by my body, breath and movement, and the resistance inherent in the clay. The work speaks about vulnerability and fragility, but also about the circle as a universal symbol. The relation between human beings and machines has been my main focus for the last fifteen years,’ he adds. He says a key point about the twenty-minute-long performance is its slow pace. It seems like time has stopped. Afterwards, the public told him that during the performance, the smallest sounds and movements became important.

But returning to the Korean biennial where Circle II is on show: ‘The biennial is professionally produced in all its details, and the organisers follow up [with] the artists,’ says Erland. ‘I have just received good photographs of when they unpacked the work, detail pictures of it, and also pictures taken after it was mounted. Many Norwegian institutions could learn from this,’ he adds, saying that he would have loved to have been there but, alas, not this time.

Ceramics: an opportunity for exploration and

research

Why did you choose to study ceramics?

‘Life is full of coincidences. For a long time, my dream was to work with

painting or sculpture. I started a family fairly early and enrolled in Bergen

Kunsthåndverkskole (the present-day Bergen National Academy of the Arts) in

1966, aiming to study something that would offer financial security. The school

provided a basic education and functioned as a formative arena for many artists

– Terje Westfoss, Bård Breivik, Yngvild Fagerheim, Arvid Pettersen, and

Kristian Blystad, just to name a few. It was like a melting pot where you could

move from department to department just as you pleased. It was a rich and

wonderful environment in which to experiment. After a while I discovered

something that has been very important for me: ceramics offered more

opportunities for exploration and research than did the other genres of art.

The traditions in the field did not seem as burdensome as in sculpture and

painting.’

Erland relates that after completing his studies, he taught at the school for a year – during what he describes as a period of momentous change. He then applied to other schools and was even offered a place at Helsinki’s art academy, but ended up in a ceramics collective in Brusand, on the coast of Jæren (southwest Norway). He remained there from 1972-75 and took part in several group exhibitions. After this, he earned a living by working in industries and in a kindergarten, and by drawing portraits and painting watercolours. In 1986, he and his wife, the ceramic artist Karen Erland, set up their own wood-fire kiln workshop, Smiå keramikk, in the town of Bryne, also in Jæren. Erland and his wife ran Smiå keramikk for twenty years, before moving the wood-fire kiln to a larger workshop in another part of Bryne.

‘Collaborating with Karen has proved very fruitful for me. We have a neverending conversation. We use each other in our work, and offer each other criticism when we want it. We have worked together for almost thirty years,’ he says.

‘Working with a wood-fire kiln makes it possible to create something that is precise in expression yet also unpredictable,’ Erland explains, referring to Jorunn Veiteberg’s essay in the book Jens Erland: Kompositt (Composite): ‘Wood firing gives his works a warm, uneven glow and a dynamic appearance, and often serves as a surprising and expressive contrast to the taut and precise style that otherwise characterises his work.’1

‘Using a wood kiln was a choice inspired by the Japanese craft tradition, via Bernhard Leach,’ Erland explains. ‘This is an artist we discovered in the 1960s. And on the island of Sotra [near Bergen], there was a flourishing artistic circle with Odd and Kari Gjerstad at the centre. They used a kiln that ran on oil, and it offered a fair amount of materiality, but the wood-burning kiln offers even more.’

Industrial environment as artistic potential

Erland underscores the significance of growing up in Jæren, where his family on both his mother’s and his father’s side produced agricultural machinery. He thus grew up in an industrialised environment. While travelling in Japan in 1990, he felt a strong need for re-orientation. He relinquished the more overt Japanese ideals and began to consider the artistic potential inherent in his own childhood environment. ‘I later recognised that my reaction coincided with a global trend. Postmodernism liberated our mode of thinking,’ he reflects.

‘In 1990, I felt the need to re-orient myself, but I did not know whether the direction I took would lead anywhere. That is how I work; I do experiments in a certain direction, but do not know beforehand exactly where they will lead. As the Danish artist Robert Jacobsen put it: “I don’t know what I’m looking for, but I know it when I see it.” I can relate to this; it is a method of deliberate experimentation combined with intuition.’

I once read an interview with you where you said that the idea of combining ceramics and air filters came about through intuition. Can you say more about this?

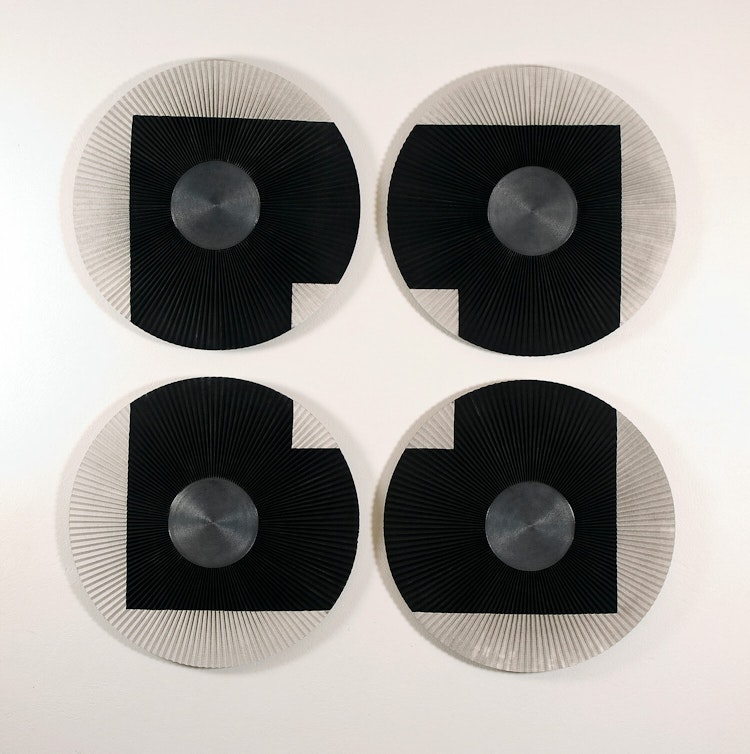

‘It was in 2001, while I prepared for the travelling exhibition Metamorphosis, which centred on the theme of recycling, re-use, and transformation. This was after I had used large rubber bellows in the two series White Top and Sensual Pair. I had also begun the series Circular Dish. One day, while I was at an excavator machine garage searching for large rubber bellows, I found a used air filter in a dumpster. Back in my own workshop, late one night, I pulled out the air filter, cut away the steel lattice and removed the dusty filter paper. It looks like a fan if you hold it in a circle. Intuitively, I put it around a circular dish lying on the table. This was the starting point for the first work in the series lovedeathdust. It was a momentous event – one of the greatest I have ever experienced. I called Karen to get her reaction and it was like an eruption! I saw a whole landscape of possibilities. Since then, I have developed the theme. Tender is a series of light, unused filters, and the travelling exhibition Paradigm includes one work from this series entitled Constellation with Square I, which contains four light fans.’

The Bible as a charged object

Industrial materials are not the only things Erland incorporates into his

ceramic works. He has recently made a series of modified Bibles.

‘The Bible series was first exhibited in 2009 at Galleri Kunst 1.no, in a joint exhibition with Beth Wyller. Four works from the series will also be on show in October in the exhibition B.T. 2011 at Galleri Format in Bergen. The show is curated by Heidi Bjørgan in connection with the seminar Making or Unmaking? For me, the series has to do with the idea of re-use. I am curious about what kind of interventions one can do in the Bible, given that it is such a charged object.’

Erland locks all the pages of the Bibles together and combines them with ceramic and industrial materials and the roots of horses’ teeth. Over the contents of several of these works, a powerful magnifying glass is placed. It turns or skews the content when the viewer moves.

‘Regardless of the genre, I think art should offer something visual. Even when you have powerful concepts, there can be “visual food” in an artwork,’ he says.

Insight and liberation

You once said something striking which has been quoted by others: ‘The objective of the art-oriented craft artist, as for the art-oriented visual artist, is not to produce objects, but rather to gain insight (erkjennelse) and liberation.’ Can you tell me more about the background for this assertion

‘During the 1970s and ‘80s, craft artists in Rogaland “battled” with visual artists in trying to set up a joint gallery. The visual artists exploited their hierarchical position – they did not want to be “sullied”. The problem finally resolved itself through historical developments, with craft artists working in art-oriented ways. This was the context for that assertion. I am a member of both the Norwegian Association for Arts and Crafts and the Norwegian Visual Artists’ Association, so I understand the problem from both sides. But in art school, I was not imprinted with the idea of there being a distinction between art and craft. One could work as an artist regardless of one’s specific field. Perhaps this differed a little from the climate at the Oslo school?’

‘My hope is that those who use my works will experience the same – that it will give them new insights. As Nina Malterud pointed out in her opening speech at my exhibition in Stavanger, “Insight and liberation may be large concepts – but art needs strong reasons for doing what it does.”’

Postmodernism’s vitalisation

‘Composite ceramics’ is your own term for works that combine ceramic and industrial material. But what do you think about a concept like ‘Postindustrialism’?

This is an important concept. In the book Postmodern Ceramics, Mark Del Vecchio launched the concept and put it into context. Garth Clark wrote a clarifying introduction about the influence of Postmodernism on ceramics. He states:‘Postmodernism and ceramics is a marriage made in art world heaven. This particular nirvana, shielded from Modernism’s disapproving scowl, is brightly patterned, unconcerned about reverence for authorship or originality, ready to quote styles from the medium’s long past at the drop of a slip brush, and prepared to mine every semiotic meaning inherent in clay, glaze, pottery, and utility. This has liberated ceramics, allowing it to express its historical literacy, its humour, and its relationship to both everyday life and the decorative arts.’1

Clark shows how Postmodernism vitalised ceramic art by abolishing Modernism’s censorship. It is worth mentioning that two Norwegian artists, Søren Ubisch and Inge Pedersen, are presented in the book, with pictures and biographical information,’ Erland adds.

The craft-artists’ allegiance to the idea of ceramics as an alternative to industrial production was relaxed. This allowed for new strategies, for instance, to take the enormous store of knowledge which has accrued in ceramic industries and to use it artistically,’ says Erland. He sees Postmodernism and Postindustrialism as constituting a clear paradigm shift, and thinks the results of the shift will become more evident with time.

‘Jorunn Veiteberg talks about three paradigm shifts, the latest being in 1980 with Postmodernism. This is also a theme for the conference Making or Unmaking? (In Bergen, 27-29 October 2011). I see this conference as one of the most interesting upcoming events in Norway, and it will feature top professionals from several countries.’

International impulses

Erland has often exhibited his works at international venues, and twice at the arts and crafts fair Collect in London.

‘It was thrilling and inspiring. I saw so many interesting works at Collect as well as at other exhibitions. These were great experiences. The first time my works were included in Collect, in 2007, I sold a large fan from the Tender series to the Rothschild Collection. It gave me a boost. Since then, several other works have been sold. The inclusion of two interesting Norwegian galleries at Collect in recent years has drawn some attention from abroad,’ he says.

In 1990, Erland and his wife Karen took a long study tour to Japan. They have also been in China, and in 2008, both participated in an international exhibition in Shanghai. Erland thinks it is probably coincidental that he has been to the Far East so often, but it is partly through inspiration from Bernhard Leach.

‘China has a grand tradition, the consequences of which are both good and less good, but now the Chinese have a more contemporary orientation. Perhaps they will soon run neck-and-neck with the Japanese and Koreans. They are still at an early stage. The exhibition Karen and I participated in was one of China’s first large international ceramics exhibitions. The organiser and primus motor was Yushan Zhang, an artist and respected writer in his forties. He took care of all the guest artists in the very best way,’ says Erland.

Born, not made

While reflecting on his Far East connections and his recent exhibition in Stavanger, Erland brings up the subject of his ongoing series Homage to Soetsu Yanagi. At Gallery Skur 2, he presented six objects from this series. He relates that the series ‘emerged’ last year when he spent a fortnight at the Norwegian Technical Porcelain Factory in Fredrikstad, throwing large sculptural forms and using a large, vertical, manual potter’s wheel that can handle from one-half to up to almost a ton of porcelain clay.

Why do you describe the series as ‘giving homage’?

‘Since I now look critically at our admiration of Bernhard Leach back in the 1960s, and at how I cultivated the traditional craft-related values which Leach, Yanagi, and others propounded, this all requires an explanation,’ Erland says.

‘Soetsu Yanagi, on account of his essays in the book The Unknown Craftsman, was a front figure for Mingei, a folk-art movement in Japan in 1926. In the book he writes about the 16th century tea masters who introduced the tea ceremony. They sought “naturalism” to the extent where ceramic objects were supposed to look as if they were “born, not made”. Yanagi turned this thought into a slogan in the book,’ explains Erland.

He relates that one day at the Fredrikstad factory, he found some reject porcelain pieces lying next to a huge clay mixer; they had an expression he immediately identified with:

‘They had a powerfully expressive yet innocent character that somehow paralleled my Diary series, which I had exhibited at the Korean biennial in 2005. I carefully selected the pieces of refuse I could use, and refined and adapted them for my own works.’

They were “born, not made”, not by hand but by machine. Hence, this becomes a genuine homage to a philosopher who I admire on account of his essays, yet at the same time find myself critical to, given some of the consequences of his teaching

‘They were “born, not made”, not by hand but by machine. Hence, this becomes a genuine homage to a philosopher who I admire on account of his essays, yet at the same time find myself critical to, given some of the consequences of his teaching,’ Erland says.

‘In retrospect I can see, and I agree with Garth Clark when he says that the socialist-oriented Modernism’s rejection of craft-based art – not least handmade ceramics – left the field of craft-based art to conservative anti-modernists. Clark believes Leach stood for a regressive anti-art attitude, a purist attempt to preserve traditional values. With this as background, Postmodernism has, through its great diversity, become a strong revitalising force within the field of ceramics,’ says Erland.