Runa Boger

The internationally acclaimed Polish artist Magdalena Abakanowicz (1930–2017) contributed to a new epoch in textile art in the 1960s. Her exhibitions in Norway triggered increased interest in textile-based art in the country, and her authoritative attitude as a female artist was pioneering. In this article by Runa Boger we learn more about her influence on the next generation of textile artists.

In the 1960s, Magdalena Abakanowicz created a series of three-dimensional, monumental works. In general, the reception of her works relates to this shift from two-dimensional textile surfaces to 3D sculptures made with powerfully emotive yet ‘non-precious’ materials. Hefty ropes, horsehair and sisal fibre demanded a new and different visual language and large format. Wool was in short supply in Poland at the time, so she used all sorts of other materials she found. The technique was rough and spontaneous, and the works were created directly in the loom, thus not based on drawn templates. In these works, existential challenges were reflectively expressed in the organic fibres and in the structure of the materials themselves. The works related to the socio-political context. Tactile qualities of textiles were attributed meaning and were decisive for perception. A new awareness emerged. No longer conceived as tapestries, the public experienced free-hanging objects liberated from the wall. They related to the room as a whole. The textile sculptures held figurative associations and created references to the human body.

Magdalena Abakanowicz identified strongly with Polish history, and this aspect is reflected in her art. Poland’s onerous political history has played a role in imbuing Polish art with a special character. Old values such as individualism and personal freedom have remained deeply integrated in Polish culture despite shifting political systems. Polish history has also left indelible traces in the national mindset. Idealism and creativity flourished amongst Polish artists in the 1960s and ‘70s, hence Abakanowicz’s development as an artist must also be seen in connection with the selective and art-expanding milieu in Warsaw in which she participated.1

Textile sculpture in expanded space

Magdalena Abakanowicz held two solo exhibitions in Norway in the 1960s and ‘70s. Arbeider i vev (Works in Weaving) opened at Kunstindustrimuseet in Oslo in the autumn of 1967.2 The works showed a development – from flat abstract compositions towards more distinctive 3D fibre compositions. Visitors saw textile pictures hanging on the wall but merging out into the room, with reliefs and applications. From Oslo, the exhibition travelled to Vestlandske Kunstindustrimuseum in Bergen3, the art society Stavanger Kunstforening4, and Nordenfjelske Kunstindustrimuseum in Trondheim. Works in Weaving provoked strong reactions. Most provocative, I think, was her break with tapestry as a craft discipline demanding a certain expert quality to the handiwork. The Norwegian standard at the time was that weaving should be precise and free of mistakes; the backside of a work was as important as its front. A dramatic shift occurs – from the ‘pretty’ tapestry to the Polish rough and reckless execution, in which weft and threads dangle loosely. Abakanowicz displayed a clear, personal and expressive need, and the fact of finding a form for what she wanted to express was far more important than the actual handiwork. This was a liberation: from the decorative motif as the main subject, to a personal visual language. The material became part of the work – the expressive force lay in the textile material’s own form, colour and construction. The primary concern was not to depict something, but to present an action, one in which the creation processes was important in itself. Abakanowicz’s distinctive compositions often convey a female sensuality; they are visually gendered objects that challenge formal and stylistic conventions.

Two important figures in the Norwegian art scene had opposing attitudes towards Abakanowicz’s art: Håkon Stenstadvold and Alf Bøe. Stenstadvold was a painter, print artist, and, during 1964–72, the rector of the school for applied art and design in Oslo, Statens håndverks- og kunstindustriskole (SHKS).5 He was incensed. Abakanowicz’s technique, he thought, was ‘only adequate for darning wool socks and repairing warn-out elbows on sweaters’. Bøe, however, an art historian and the chief curator at Kunstindustrimuseet in Oslo during 1962–68, was very enthusiastic. He emphasized the richness in tangible qualities, the unconventional materials, the spontaneous expression and the novel colour palette, all culminating in sensory as much as visual pleasure.

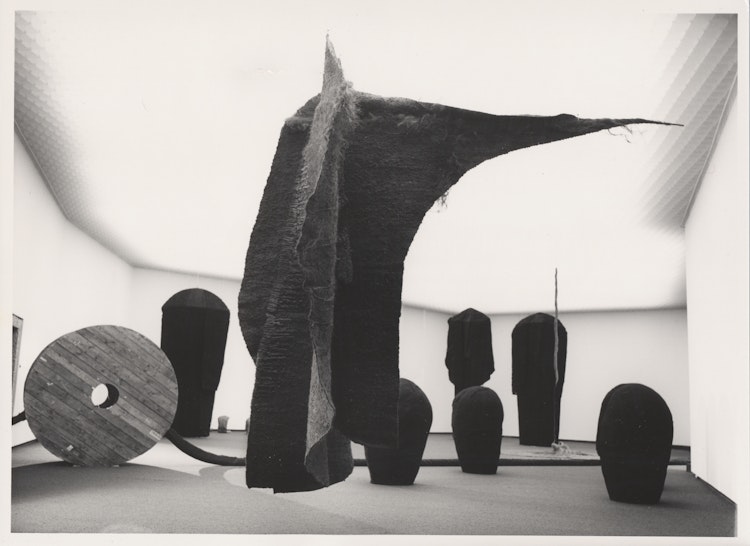

The exhibition Magdalena Abakanowicz’ Organiske Strukturer (Organic Structures), which was shown at the art centre Henie Onstad Kunstsenter in 1977, offered other challenges. It featured free-hanging and free-standing 3D objects that related to the room and the architecture. Because the public could move around and in-between the objects, they could be viewed from several angles. This resulted in a more direct mode of contact between the public and the works, for they were not simply viewed from one angle as 2D textiles. By ‘taking possession’ of the room, the works gained greater dramatic force and expression.

This exhibition marked the first time in Norway that the public experienced complex installations, that is, textile sculptures in an expanded field; they experienced an environment in which the concept of the work, the space and the milieu melted together. The exhibition space with all its elements became an independent work of art – a performance, or an absurd theatre.

The Polish wave

Poland was an important contributor to textile art’s development as an autonomous art form. In the 1930s, a national effort to renew Polish woven art led to the establishment of separate textile study programmes at Poland’s art academies. Textile art thus gained recognition as pictorial art in Poland, while in most art circles in Norway, there was still strong resistance to the idea that textile works could be ‘fine’ art. There was no textile study programme at Norway’s one art academy, so students applied for government study grants and enrolled in Polish art academies. They created works that became significant for the recognition and development of textile art in Norway.

Brit Fuglevaag and Siri Blakstad were students at SHKS in the late 1950s and early ‘60s. They were fascinated by Eastern European art and culture. Poland was experiencing what could be described as an explosion in creative ideas: it was a pioneering country in avantgarde theatre, contemporary music, modern filmic art, and, not least, in printed art and poster art.

Brit Fuglevaag was the first Norwegian textile artist to study in Poland.6 After completing her studies at SHKS, she applied to study in Poland because the academy education there included study programmes in textiles. Her choice of which art academy to apply to related to the school’s status. Fuglevaag attended the art academy in Warsaw during 1963–64. In 1970 she started teaching in the textile department at SHKS. She came as a breath of fresh air from the big wide world, bringing alternative ways of thinking within an international trend. Fuglevaag represented free-spiritedness and shunned conventional views on textiles. She worked in what could be called a Polish visual idiom.

Fuglevaag introduced new ideas about what textiles could be and how they could be made. Her work capacity and enthusiasm spread to the students. Experimental classes were held on Saturdays, and students could use any fibrous materials they wanted. A loom was no longer the only means for creating woven textile art. The students made primitive weaving frames and used them to experiment and create different expressions. Fuglevaag was a powerhouse, both as an artist and as a mediator who gave others access to a professional field. One of the most important experiences she had in Poland was to see that artists there were taken seriously. She learned to be proud of being an artist, and she passed this attitude on to the students.

Siri Blakstad attended Warsaw’s art academy in 1964.7 It was, she claims, one of the few places in the world at the time where one could work with tapestry. Blakstad was initially interested in painting. She was most of all interested in form, an abstract formal language and French Impressionism. Poland had close collaboration with France, and several teachers at Warsaw’s academy had studied in Paris. In contrast to Fuglevaag, Blakstad was interested in Abakanowicz’s works. She contacted Abakanowicz and eventually got a place at Atelier Experimental de L`Union des artistes Polonais, where Abakanowicz worked.

When asked about the difference at the time between textile education in Norway and Poland, Blakstad says that in Norway, there was no freedom, and that at SHKS, weaving was supposed to be ornamental and to involve a limited use of colour. Kjellaug Hølaas led the textile department and was a strict Modernist who did not allow rupture in a planar pictorial field. Moreover, one should restrict oneself to the rectangular format. Blakstad experienced that Abakanowicz’s way of working gave her an opportunity to create directly in a weaving, just as in a painting, without a preliminary drawing. Experimental weaving gave her a possibility to create, change and add elements while doing the actual weaving. Back in Norway, Blakstad’s textile entitled Poland was accepted for the exhibition Høstutstillingen in 1966.8 The work was made with unspun wool and horsehair that hung loosely outside the warp, like fur. Another chief characteristic was the composition’s abstract form in black and white. Sharp contrasts in the light and dark passages accentuated the composition’s tension and connoted a dramatic dimension. This work, which drew much public attention, put Blakstad in a position to win a coveted prize from the newspaper Morgenbladet. All the newspapers in the country reported on Poland and printed whole-page interviews with the artist.

The critics’ enthusiasm and recognition contributed to increased interest in textile art. Architects became aware of the new textile style – it seemed to be created specifically for modern architecture. The rough use of materials, the monumental size and rugged expression were well-suited to cement Brutalism and brick walls. Poland was purchased for the new premises of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Norway gained an artwork that was new and modern in the Norwegian context, at the same time as the work participated in an international avant-garde movement.

In time, other students went to Poland: Eli Nordbø attended the art academy in Krakow in 1971 and the art academy in Warsaw in 1972/73; the undersigned attended the art academy in Lodz in 1972/73; Bente Sætrang attended the art academy in Poznan in 1974 and was tutored by Professor Abakanowicz herself. Synnøve Øyen was also a student at the academy in Poznan (1997/98).

A door opener

Abakanowicz’s exhibitions in Norway came at a time when there was a revolt and great change in Norwegian textile art. Strong political currents and a dawning women’s movement paved the way for an artistic liberation. Abakanowicz’s enormous self-confidence and large solo exhibitions were completely different from what women artists were used to seeing at the time. Her art reflected a change in the way of seeing textile art and at the same time strengthened women artists’ self-confidence and possibilities. Her art was a manifesto both for women artists and for an art form that was on the verge of expanding, from being seen as craft to being accepted as autonomous art. Her unconventional works opened the door to new perspectives within textile art.

In Norway, a battle was being waged to distinguish textile art as an independent art form, not beholden to any rules other than those which each work sets for itself. At the time, textile art, like photography, was not accepted as ‘fine’ art. Abakanowicz’s exhibitions were therefore important for putting a spotlight on an art form that was accepted as such in Poland, and for emphasizing a female textile artist who had achieved international recognition.

One reason for this recognition was Abakanowicz’s use of sisal (a fibre from the agave plant, Agava sisalana). This fibre, due to its construction, eventually became her most important material. Sisal is cultivated in Poland, and it became an alternative fibre at a politically turbulent time when wool was difficult to access. Sisal is characterized by weightiness and strength. These qualities enabled her to construct large and stiff 3D works, as in those called Abakans. Furthermore, sisal’s ability to absorb dye results in a saturated colour expression that adds tactility and sensuality to a work. The choice of fibre, however, was only part of the reason why Abakanowicz’s works caused such a stir. It was not merely a matter of technique and material, but also of content and the use of symbols. The erotically charged works, even the large capes, expressed content and meaning and had a sensual aura.

The fact that a woman artist dared to do what Abakanowicz did made an impact, and it cannot be isolated from what was happening elsewhere in society. A so-called ‘sexual liberation’ was taking place at about the same time. Abakanowicz’s exhibitions in Norway were therefore an inspiration to Norwegian artists and opened possibilities within the textile field where women already had experience. During that same period, Norwegian women artists gained greater awareness of the conditions under which they worked, and this was significant for the development of art policy and professional organization, as we shall soon see.

The 1960s was a time when attitudes were changing over what textile art could be, but just as important was the change in artists’ relation to the society. The field of textiles had traditionally been defined as belonging to the craft disciplines. At SHKS, teaching was based on the principle of the rational, handcrafted production of textiles to be used in the home or workplace. An important aspect of this principle – one which set the tone for the era – was Scandinavian Design, which emphasized the creation of everyday goods and beautiful homes. The students in SHKS’s textile department eventually wanted to do things their own way, to follow their own paths – they wanted to be artists.

While, in the 1960s, a new awareness emerged regarding textiles as a specific field of art and the possibility of a textile being a work of art, in the 1970s, there was increased awareness of the position of artists in society and the role of an artist. This involved reflection on the decision to have a career as an artist and cultural worker. Women’s liberation was a watchword for the era; a battle was waged to gain acceptance for the idea that women who chose to be artists actually chose a career; they were not just working to create beautiful homes for themselves. Important in this process was to establish workshops and studios outside the home and to have them be defined as workplaces. The series of cross-disciplinary and coordinated political agitations referred to as Kunstneraksjonen (Artist Action) in 1974 created an awareness amongst textile artists that political organization was a tool for affecting art policy, and it contributed to a situation in which their identity as artists was a source of pride. It was in this eventful and revolutionary period, more precisely, in 1977, that a national organization for promoting the interests of textile artists – Norske tekstilkunstnere (Norwegian Textile Artists) – was established, as a foundational organization within Norske Billedkunstnere (the Association of Norwegian Visual Artists).9

Style creator or liberating role model?

What sort of significance has Abakanowicz had in Norway, and can we distinguish between the art and the artist? Have her works been a stylistic influence, or has she been a liberating role model for young women artists in Norway?

In retrospect, it has become clear that Abakanowicz’s material-based expression was insufficient for creating a new stylistic trend. This is because the Norwegian textile tradition has been so strong. In a small survey conducted amongst Norwegian textile artists in the autumn of 2009, respondents were asked, among other things, about Abakanowicz’s influence.10 Most answered that her authority as a woman artist inspired them. For respondents who were weavers, Hannah Ryggen and Synnøve Anker Aurdal were strong role models. Textile print artists were more concerned with formalism in modern art, or ornamentation in folk art, and for some of these artists, Gro Jessen was said to be an important role model.

None of the Norwegian artists broke as radically as Abakanowicz did with the tapestry tradition, but the inspiration and influence from the ‘Polish wave’ opened their eyes to new perspectives. After the break with tradition, there were some years in which they used a diversity of materials and experimental techniques. In the early 1980s, the Polish-inspired tapestry disappeared as their attention turned to other pictorial textile expressions. An expanding field of innovative printing came to the fore in Norwegian textile art. Abakanowicz was important because she showed that it was possible to make a breakthrough as a female artist. She tore down the fence that had long cordoned off the conventional sphere in which women artists could work. Greater freedom in modes of working loosened up the textile discipline and made experimentation possible. This provoked some people, but at the same time, it gave women artists new opportunities.

Abakanowicz’s influence seems most of all to be that she acted as a role model for women artists in Norway. She was an exponent for a new and unfettered attitude to a tradition-bound art form. First and foremost, she set a standard for being a woman and an artist.

Is there any interest amongst younger Norwegian artists today in Abakanowicz’s way of thinking and working?

It is difficult to know the extent to which there is any general knowledge about Abakanowicz’s textile works amongst younger artists today. In the 1970s Abakanowicz stopped weaving. And in contrast to her flexible woven works, she began using industrially produced materials to create, among other things, cast sculptures that were hard and inflexible. This marked a decisive break with textile art. She did not want to be defined as a textile artist or be part of the feminist movement. She built for herself an international career and produced a series of outdoor projects, often in places with a tragic history, for instance in Hiroshima. It is for these works that she is most known in the wide international artworld.

But back to the question. What we can see today in Norway is a greater interest in material-based art. Woven textiles have enjoyed a renaissance, and more artists than ever before are working with tapestry, albeit in a more traditional and rule-bound way. But there are exceptions. Two young and ambitious artists, Aurora Passero (1984) and Ann Cathrine Høibo November (1974), both work with weaving. Their works are different, but what they share is a will to experiment in unconventional ways with materials, techniques and forms of presentation. The Norwegian artist who perhaps shows the greatest affinity with Abakanowicz’s way of working is Gunvor Nervold Antonsen (b. 1974) – not as a weaver, but as a woman artist. Nervold Antonsen has a corresponding internal force and tension in all she does. Her energy, work capacity, persistence and belief that there are no boundaries can all remind us of Magdalene Abakanowicz.But back to the question. What we can see today in Norway is a greater interest in material-based art. Woven textiles have enjoyed a renaissance, and more artists than ever before are working with tapestry, albeit in a more traditional and rule-bound way. But there are exceptions. Two young and ambitious artists, Aurora Passero (1984) and Ann Cathrine Høibo November (1974), both work with weaving. Their works are different, but what they share is a will to experiment in unconventional ways with materials, techniques and forms of presentation. The Norwegian artist who perhaps shows the greatest affinity with Abakanowicz’s way of working is Gunvor Nervold Antonsen (b. 1974) – not as a weaver, but as a woman artist. Nervold Antonsen has a corresponding internal force and tension in all she does. Her energy, work capacity, persistence and belief that there are no boundaries can all remind us of Magdalene Abakanowicz.