Helene Duckert

In this call-to-action essay, artist Helene Duckert offers up a myriad of ideas, prompts, and discussions to fuel change and engagement through craft, written with the intention that it will remind the readers of their fundamental responsibilities.

Sometimes I don't feel like writing because

everything is connected and I can't get into all

that right now.

What is the difference between looking and observing?

What’s the recipe for peace?

Pussyhats

Ironically pink to show a lack of choice

Resilience is a myth

Gentle and respectful form of activism

Nice crime

Who’s my little activist?

What is activism?

Why do we do it?

Rithms of the Night

Algo-riddims

Al Gore Rhythms

AI-generated etymology for “algorithm” in the voice of a Persian man:

Ah, my friend! The word "algorithm" comes from the name of a brilliant Persian mathematician, Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, who lived in the 9th century. His work laid the foundations for algebra, and through Latin translations of his writings, his name transformed over time into "Algoritmi". So, when we say "algorithm", we are actually honouring the legacy of a great Persian scholar who contributed so much to mathematics and science!

It’s strange.

I don't know if they know yet,

but suddenly,

there was no other way out.

There are some of us who are trying to save the future.

I don't know if we're doing it right.

I don't know if it’s going to work.

What is work?

Pleasure and pain.

Tangible artefacts of dissent.

Do we need more stuff?

Love letters.

I leave for Beirut tomorrow.

What is considered a gift?

Today, I’m diving into “craftivism” — a term coined by Betsy Greer in 2003 that merges craft with activism, embodying hope and creativity.1 However, amidst political chaos, environmental catastrophes, and social upheavals, I ask myself whether stitching slogans or knitting for a cause really can make an impact? It’s not that I lack faith in art’s transformative power; it’s just that sometimes these gestures feel like putting a Band-Aid on a hurricane. Can a hand-knitted scarf really help solve climate change?

Ever since my sleep schedule went haywire around 2020, and my phone morphed into a permanent distraction device, I’ve found myself mesmerised by the world of digital artistry. Memes and videos with sharp, witty commentary are now my go-to for modern protest. While craftivism has its cozy appeal, I’m intrigued by how digital artists are flipping activism on its head. Is it possible that “craft” can transcend its physical limitations and wield just as much influence through lines of code and pixels? Or are we just adding more noise to an already chaotic digital symphony?

Each one is a potential flame

The technique of crafts, with the goal of activism — it sounds good, but why am I not feeling it? My initial reaction to the term “craftivism” is to reject it altogether. It simply doesn’t resonate with me. It feels too passive, too gentle, too quiet, and ultimately self-congratulatory without substantial context. While I can appreciate the personal journey that comes with crafting, or the joy of discovering something lovingly made by someone else, I can't help but feel that this doesn’t drive significant change.

In the BBC documentary Craftivism: Making a Difference Sarah Corbett emerges as a prominent figure in the UK’s craftivism scene, but this isn’t the raw, radical activism that many of us crave. At the 2014 Campaigning Forum,2 she acknowledges her past in more confrontational tactics but paints those methods as potentially “anti-social” or “illegal”, essentially labelling them as too extreme for her comfort. By elevating craftivism as a softer alternative, does Corbett risk diluting the urgency that activism demands?

Corbett’s self-portrayal potentially veers into the realm of cliché, using her introversion almost as an excuse to sidestep the chaos and noise of more traditional forms of activism. With a sprinkle of humour, she deflects conventional expectations by admitting to her love of Vogue and her non-vegan choices — relatable, but I’m cringing at her attempt to distance herself from a revolutionary image that some find uncomfortable or radical. As the founder of the Craftivist Collective in London, she receives a substantial platform, but her approach feels more like Sunday tea rather than a fight against oppression.

I experience this self-congratulatory style as a systemic problem that raises the question: Is craftivism offering a safe space for privileged individuals to pat themselves on the back while the world burns? This notion of gentle, artistic engagement could just be a veil for avoiding the stakes of radical action, allowing urgent social justice issues to simmer quietly rather than explode into necessary revolt. Do we want a polite conversation, or do we want to ignite a revolution?

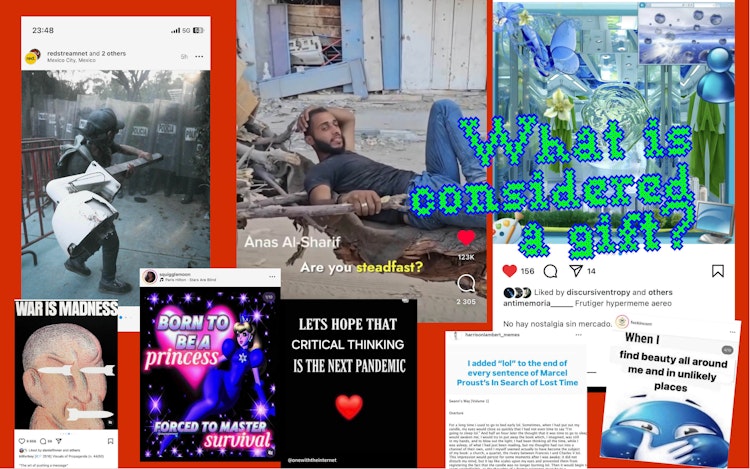

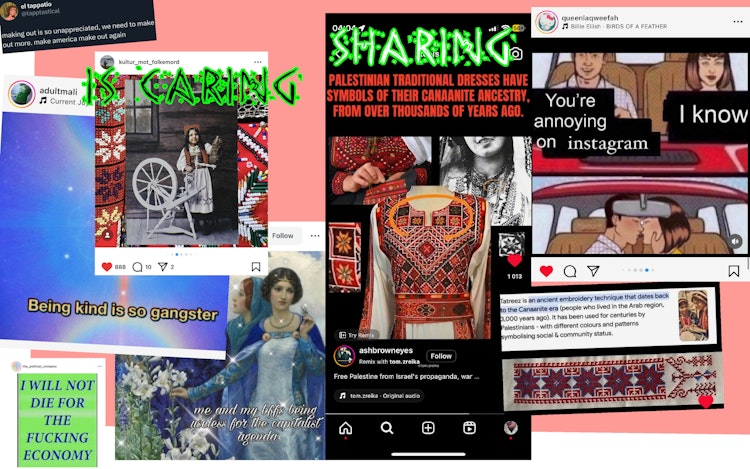

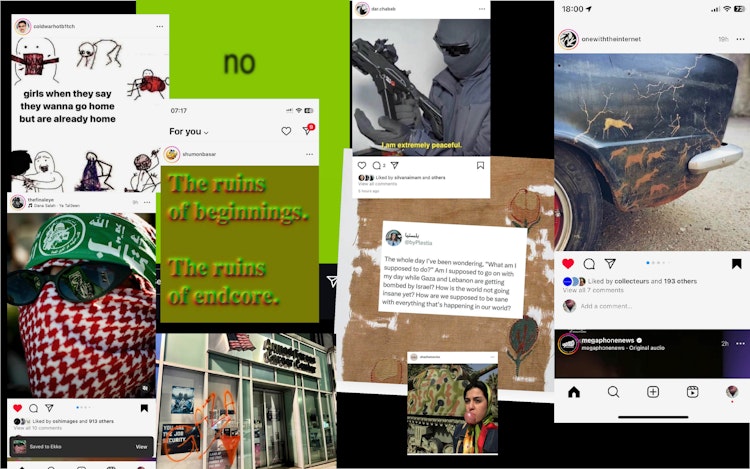

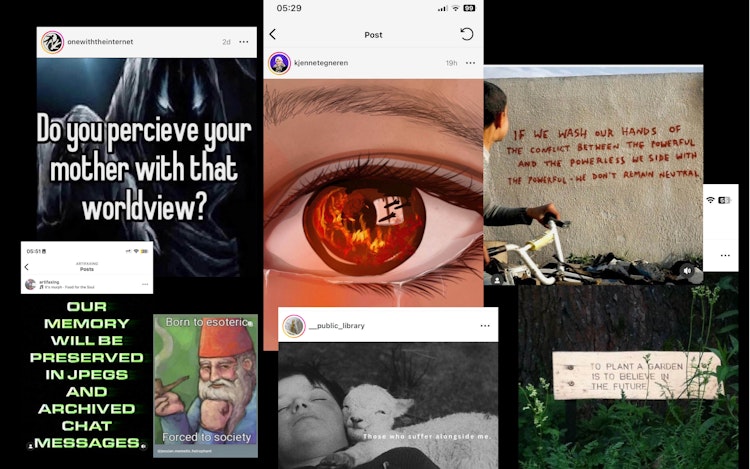

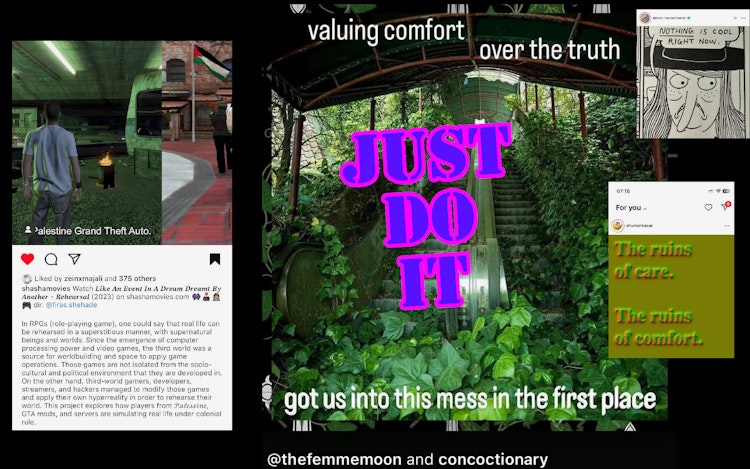

Collages by Helene Duckert

Kaleidoscope of absurdity

In our hyper-connected yet fragmented digital age, finding a sense of collective identity and belonging feels like searching for a unicorn in a haystack. It’s not just about joining online groups; it’s about how these spaces help us feel connected amidst the tsunami of information and clashing viewpoints. The internet mirrors our diversity and serves as a canvas for our beliefs, but can it really hold up as a genuine space for connection, or is it just a giant echo chamber where we all shout into the void?

Navigating these questions means embracing empathy and understanding across different perspectives. Can social platforms truly offer meaningful conversations that honour a wide range of identities and experiences, or are we doomed to be trapped inside our digital bubbles? For now, let’s celebrate our differences while figuring out if we can turn this digital chaos into something resembling unity — without succumbing to the cringeworthy absurdity of it all.

Burn Baby Burn

As I write, my frustration grows at how the world often stands by in times of crisis. I feel a compelling urge to break through the apathy. How can I ignite your passion for action? How can I make you care?

Teamwork is supposed to make the dream work, and I want to see you challenge the status quo, dismantle systems of oppression, and make a difference. We are all navigating busy, stressful lives with personal challenges, but this doesn’t excuse you from the urgent need for global, collective change. Without it, survival is at risk — and that’s a heavy burden to bear.

Ladies Sewing Circle and Terrorist Society

Scrolling through Instagram, I encountered a post from the account Onewiththeinternet featuring a garment emblazoned with the phrase ‘Ladies Sewing Circle and Terrorist Society’. Intrigued, I learned that in 1974, a feminist group in Eugene, Oregon, used this mock organisation to challenge conventions and disrupt state structures through textile-making. This concept links to the modern practice of “craftivism” — the political and social aspects of hand-making that engage with debates on process, materiality, gender, and race, as explored by art historian Julia Bryan-Wilson.3

In a 2014 YouTube clip titled ‘Julia Bryan-Wilson is Totally Badass’, she critiques the professionalisation of art, which often prioritises market values over genuine artistic expression and activism. The role of the professional artist has evolved, influenced by formal education and funding systems that favour established standards of success. Bryan-Wilson reframes the question from ‘Should artists professionalise?’ to ‘How should artists profess?’ This encourages a deeper exploration of artistic motivations, challenging the notion that art must conform to capitalist or neoliberal frameworks to be legitimate.

In this light, craftivism emerges as a resistance against the commodification of art. By prioritising community involvement, sustainable practices, and creative democratisation, craftivism opposes neoliberal values such as individual success and profit. Craftivism then, advocates for social impact over financial gain, aligning with anti-capitalist ideals of solidarity and cultural connection.

While craftivism seeks to reclaim the value of crafting and address societal issues, it also highlights the divide between fine art and craft. Craft is often dismissed as lesser, marginalising those who advocate through accessible, hands-on methods. Bryan-Wilson’s vision of professionalism rooted in social justice rather than market demands challenges us to rethink our roles and privileges within systems of power. By redefining professionalism, artists can reclaim their agency and use their work as a catalyst for social transformation.

Craft-a-God

Both craftivism and digital content creation cultivate communities, yet they do so in different ways. Craftivism is about the handmade, creating connections through the tactile and the joy of making something with your hands. It’s intimate and grounded, fostering unity in the thoughtful, slow process of crafting. Time and care poured into each piece serve as acts of resistance, potentially transforming individuals across the globe into a united force for change.

In contrast, digital content creation offers a different vibe of solidarity — immediate, expansive, and interactive. Thanks to social media and on-demand content, it allows creators to connect in real time, where they can ignite widespread discussion and mobilisation with a single post. This type of activism leverages the speed and reach of the internet, forging a network of creators and activists to share ideas like never before. While craftivism builds solidarity through shared, hands-on experiences, digital content creation energises it through an exchange of ideas. Together, they create a synergy, balancing the slow and deliberate with the fast and broad, enhancing one another’s capacity to inspire and drive social change.

In today’s digital landscape, content creation serves as a means for advocacy for social causes. Memes, a form of internet folklore, exemplify this trend by spreading rapidly across online platforms. At their core, memes are ideas, behaviours, or pieces of media that catch on quickly, often infused with humour or relatability.

Sharing is caring

Let’s talk about memes. These cultural snippets, akin to snapshots of our evolving societies, are images or ideas designed to capture attention through shared experiences and desires. In internet culture, memes usually take the form of images, videos, or text centred around specific themes, jokes, or cultural references. They are dynamic and evolve as users add their takes and variations, creating a viral chain of content.

Consider memes as modern jokes — crafted and reshaped to fit various contexts. They reflect our collective creativity, allowing creators to spread their ideas to a vast digital network. Memes are not solely about humour; when a meme transcends the ordinary, it can reveal truths about love, human connection, and my passions, resonating with me long after viewing them. This combination of insight and emotional impact draws me in, turning my scrolling into an exploration of ideas and feelings.

Web 2.04 is the place where all of this unfolds — it’s a space for social interaction where I can create and connect, where I can share thoughts and ideas. Each meme serves as a reminder of my collective engagement with the digital world. In this era of interactive internet, we’ve shifted from merely consuming content to actively sharing and communicating. This transformation has also redefined craftivism, turning it from a niche movement into a global phenomenon. Social media enables craftivists to amplify their messages and rally communities around shared causes.

However, increased visibility raises questions about engagement. Has the ease of sharing and posting fostered a culture of superficial activism, in which people are more inclined to post about a cause rather than truly commit to it through everyday actions?

The digital landscape of resistance

We find ourselves at a crossroads. Modern technology, especially smartphones and social media platforms, allows us to witness global atrocities in real time, creating a heightened sense of urgency and interconnectedness among activists worldwide. Yet, with every scroll and post, a pressing question looms: how do we convert digital outrage into meaningful action?

Social media and digital content creation play pivotal roles in today’s social movements. The pro-Palestine student encampments that erupted globally in 2024 epitomise this phenomenon. Young activists harnessed their camera phones and digital platforms to amplify their voices in mainstream discourse. Platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and Telegram became places of protest, uniting geographically dispersed individuals in collective efforts to spotlight injustices. They transformed moments of resistance into viral phenomena, reminding us that visual storytelling can evoke empathy and inspire action on a global scale.

This digital revolution is also reflected in the recent uprisings in Bangladesh, where citizens have rallied against systemic corruption and environmental degradation. Here, social media has acted as both a platform for organising and a means of crafting a narrative that defies oppressive state-sponsored censorship. The immediacy of sharing experiences and strategising protests online, coupled with dramatic imagery captured on smartphones, has propelled these movements into the spotlight, showcasing grassroots resistance as it unfolded in real time.

However, these movements starkly contrast with the chaos in Sudan, where civil (proxy) war has left the population caught in the crossfire of international power struggles. While Sudanese activists have been successful in utilising digital platforms to raise awareness about their plight, the scale of displacement and violence complicates their efforts. In this context, social media becomes a lifeline — a way to draw attention to the horrors experienced on the ground, yet it also highlights the vulnerability of movements dependent on external engagement and solidarity. The power of narrative, while potent, cannot shield a people from the devastation wrought by global interests.

IRL

Amid these splintered resistances, an unsettling irony emerges: our reliance on war-torn regions like the Democratic Republic of the Congo to supply raw materials for our “cheap” mass-produced electronics — devices that enable us to witness and share the unfolding of what some are terming World War III — reveals the paradox of modern existence. In our pursuit of convenience and connectivity, we remain complicit in a cycle perpetuating exploitation and violence. This systemic dysfunction satisfies our consumer desires at the expense of lives — a bitter truth that escapes our consciousness.

As a contemporary artist, I find myself grappling with the moral ambiguity inherent in our consumer-oriented society. In moments of reflection, I acknowledge that while our digital tools can foster activism and draw attention to crises, they can also serve as veils — framing our perception of these conflicts without necessitating deeper engagement or accountability. This detachment creates a troubling dynamic; we swipe through images of suffering, yet for many, it becomes an abstraction, a spectacle to consume rather than a call to action.

The truth is that we are not yet free; we have merely achieved the freedom to be free, the right not to be oppressed. We have not taken the final step of our journey, but the first step on a longer and even more difficult road. For to be free is not merely to cast off one's chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others. The true test of our devotion to freedom is just beginning. — Nelson Mandela

Can you craft a revolution?

Now, let’s explore why these pro-Palestine encampments can be perceived as a form of craftivism. Craftivism blends creativity and activism, focusing on “amateurisms” that democratise participation, allowing anyone — regardless of expertise or background — to engage in creation. This DIY ethos prioritises personal meaning over perfection, embracing the idea that the act of creating itself holds intrinsic value.

In these encampments, the rejection of consumerism stands out. Participants utilise their knowledge, diverse skill sets, and artistic instincts — through banner-making, embroidery sessions, and various creative and interpersonal projects — to convey messages of justice and solidarity. This aligns with the core tenets of craftivism, where each individual's contribution enriches the collective narrative. Through creative practices, activists advocate for Palestinian rights while also reflecting on broader social issues, challenging dominant norms and inspiring change on both emotional and intellectual levels.

The encampments are driven by urgency — here, creativity isn’t restricted by skill level or market demands; instead, it encourages individuals to personalise political messages and reclaim narratives based on shared needs and aspirations. This transformation creates spaces where art and activism converge, serving as a tangible representation of creativity and solidarity.

In the face of global turmoil — whether it be the ongoing struggles in Palestine, the recent uprisings in Bangladesh, or the consequences of proxy wars — activism has the potential to weave compassion and consciousness into our world. Each art piece crafted, each banner raised, and each story shared in these encampments serves as a testament to the resilience of the human spirit. Their creativity fuels hope and inspires me to envision a future that transcends the exploitative frameworks we currently inhabit.

The encampments transform public spaces into places of dissent, where art and activism intertwine, lending individuals the power to utilise their diverse skill sets to craft new futures. The synthesis of personal expression and collective action, the encampments embody the will for justice in every stitch, brushstroke, and spoken word. This is where true craftivism flourishes.

Just do it

The international performance group Direct Action Theatre (D.A.T.) merges art with activism, creating an intersection where protest and performance collide — they call it “Artivism”. Their projects encompass both public space interventions and conventional theatre performances. In their series Serve and Protect, which alludes to the North American police motto, D.A.T. employs riot police uniforms as powerful visual symbols. By placing these uniforms in absurd scenarios, the artists examine and question power dynamics and the institutional role of the police.

Earlier this year, D.A.T. staged an arrest of Benjamin Netanyahu, based on the International Criminal Court's charges concerning war crimes and crimes against humanity.6 D.A.T. describe the arrest as follows: ‘The arrest takes place based on the International Criminal Court (ICC) charges of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide, guided by Article 6 of the Rome Statute. Charges include deportation of the population, exposing a group to harsh living conditions, bombing temples and hospitals, intentional killings of peacekeeping personnel, use of white phosphorus, attacks on health and transportation units, and targeting an internationally protected refugee camp. This arrest was carried out by the organization Direct Action Theatre (D.A.T.), which has taken it upon itself to address these allegations.7’ I highly recommend checking out their videos.

We’ve got content at home

Sometimes the internet feels like an all-consuming force — a tidal wave of never-ending impressions. I understand why you might want to look away. I face screens more than I face other people now, especially after the pandemic-mandated shift of many aspects of our lives online. But I have a nagging thought: how long can this last? The digital world dazzles us with its kaleidoscope of images and information, but beneath the surface, there’s a sense of fragility. What happens when the sparkle fades? Or the sun flares up? What lies ahead for us?

Personality is a kind of design problem; for example, something happens and you want to scream, but you think, “I'm not the kind of person who would scream, I'm just not,” but you still want to scream. That's basically a design problem that you can go back and — of course we get a lot of things from our parents, we inherit a lot of things — but we also design things as well. The designers — you know what I'm talking about — you design your thing. So go back into your thing and make the design a little bigger, so that you can scream if you want to scream. Don't make a rule that says that you can't scream; that’s fascistic. Make it bigger! Make it nice and big so you have a lot of room to do whatever you feel like doing – Laurie Anderson

This idea of expanding our personal boundaries resonates with me. Change is essential as we navigate the complexities of our digital and real worlds. As I wade through an avalanche of information and daily events, I strive for awareness. Witnessing ongoing suffering — whether through digital screens or real-life crises — can motivate and inspire action. But I need to be cautious not to get lost in the digital flood or the everyday grind.

It’s challenging to face harsh realities while going through life without becoming overwhelmed and paralysed. This is where craftivism can play a role — offering a creative outlet for our frustrations and grief. However, craftivism can easily become a way to escape from reality — digital or otherwise. The goal is to balance awareness of the world with the comfort of creation, finding a way to stay engaged and responsible.

Thawra

Luckily, it is possible to do both. The beauty and political weight of Tatreez is captivating. This traditional Palestinian embroidery is more than just a craft — it’s a declaration of cultural identity and resilience amidst adversity. Each stitch of Tatreez serves as a tapestry of Palestinian heritage, with geometric patterns and rich hues narrating stories of tradition, resistance, and regional identity.

Craftivism finds a natural ally in Tatreez, the traditional form of Palestinian embroidery. By incorporating this traditional embroidery into Craftivist efforts, Palestinian artisans are not only preserving their cultural heritage but also engaging in broader resistance. Tatreez becomes a medium for both dialogue and protest, amplifying messages of justice and solidarity through its symbolic and material richness.

The artistry of Tatreez lies in its meticulously crafted motifs, varying from village to village. Each pattern holds local significance and personal stories, transforming the traditional fabric into a space of cultural pride and defiance. The vibrant threads — reds, blues, and greens — go beyond mere decoration, weaving a narrative of resilience and belonging that endures despite displacement and conflict.

‘Palestinian embroidery is a centuries-old art form that’s passed between generations orally, like from mother to daughter or grandmother to granddaughter. But the art form’s survival has become more precarious — Israeli militia and settlers have displaced generations of Palestinians, who’ve fled or were expelled from their land. The dispossession has made handmade tatreez more rare and harder yet for Palestinians like Barkawi to discover and learn from. In that dearth, Palestinians are creating communal resources and digital spaces for each other in an attempt to digitize and reclaim the art form.’ — Mia Sato8

The online platform Tirazain emerged as a solution to these challenges, offering a comprehensive online library that houses over 1000 digitised Tatreez motifs. These patterns are organised by various themes, geographic origins, and colour counts, enabling users to search for specific designs that resonate with their stories. The digital archive tells tales of identity and belonging, with patterns that can be downloaded and easily used for stitching projects. This shift from physical books to a digital platform not only increases accessibility but also revitalises communal ties that have been weakened over time.9

Founded by embroidery artist Zain Masri and a collective of volunteers, Tirazain aims to empower individuals like Lina Barkawi in their pursuit of crafting traditional garments, creating a vital resource in a field where oral history and direct mentorship are increasingly rare due to the displacement of generations of Palestinians.

Barkawi’s journey began with her personal project of creating a thobe, a traditional Palestinian dress, which evolved into a two-year endeavour to reconnect with her heritage through the intricacies of Tatreez. Her experience underscores a widespread frustration within the Palestinian community: the traditional process of passing down knowledge from grandmother to granddaughter has been disrupted by conflict and displacement, making it challenging for younger generations to engage with their cultural heritage meaningfully.

When we lose our fear, they lose their power

In today's socio-political landscape, where Palestinian struggles are often marginalised or misrepresented, Tatreez has become a vital tool for advocacy and awareness. Palestinian artisans are harnessing this craft to engage global audiences, using exhibitions and digital platforms to showcase their work and assert their stories. This modern approach elevates Tatreez into a form of protest art that resonates deeply within the global discourse on human rights and justice.

However, the representation of Tatreez has faced challenges within the art world, particularly from cultural institutions. For instance, the National Museum of Oslo has been criticised for its reluctance to display Palestinian works from its collection. This issue was notably addressed in Norwegian publications such as Aftenposten10 and Billedkunst11 — the latter featured Tatreez pieces from the National Museum’s collection as a commentary on this institutional exclusion.

The Instagram account Kultur Mot Folkemord (Culture Against Genocide, KMF) sparked national debate when it highlighted the National Museum’s stance. KMF is a coalition of art and cultural workers, many of whom work at the National Museum themselves. This critique of institutional bias reflects a broader issue within the art world: the tendency to sideline or marginalise narratives that challenge entrenched power structures. Yet, this very marginalisation has spurred a vibrant dialogue around Tatreez, pushing it into the spotlight.

In this evolving landscape, Tatreez stands as a testament to the transformative power of craft. It challenges cultural institutions to rethink their engagement with diverse narratives and reshapes global conversations around heritage and resistance. As contemporary artists and activists, our role is to champion these intersections, bringing forth stories that demand recognition and respect. In embracing Tatreez and its rich, resilient legacy, we embrace a craft that not only adorns but also defends, connects, and inspires in the face of ongoing struggles.

MEMEME

In today's interconnected yet fragmented digital landscape, the search for collective identity and belonging holds profound importance. This theme reflects more than just a shared community; it embodies an evolving narrative that weaves together individual experiences with broader social movements. As we navigate our identities — shaped by culture, politics, and personal experiences — digital spaces offer both refuge and battlegrounds where these identities are crafted, contested, and expressed.

The exploration of collective identity goes beyond mere online participation; it delves into how digital communities create a sense of belonging amidst the rapid exchange of information and diverse worldviews. The internet acts as both a mirror and a canvas, reflecting human diversity while allowing us to project our own identities and beliefs. Yet, the fluid nature of digital identities often breeds disconnection, as we balance the pressure to conform with the desire for genuine connections.

As we address these challenges, the tension between curated and authentic selves becomes crucial. Idealised portrayals on social media can lead to feelings of inadequacy but also prompt important conversations about vulnerability and true belonging. We need to listen — not only to our instinct to step back but also to the voices of those who cry out for acknowledgment. By embracing empathy and understanding, we can foster connections that transcend the chaos of the digital age and consumption-driven rat race.

Ultimately, our journey revolves around our engagement with the world around us. As we wade through discomfort, let’s embrace the shimmering threads of hope woven into our collective narrative, crafting responses to suffering that are as resilient as they are thoughtful.

I’d like to conclude with a text that has followed me for as long as I can remember and has made its home in every place I’ve lived — originally a magazine clipping my father would hand out in fresh, hot photocopy versions whenever he felt it necessary:

Start Something

Throughout history

most great

civilizations that

have declined

were victims of

stagnation rather than

conquest.

Apathy,

indifference,

detachment

led to decay.

In every country today

we find more people who

prefer the role of

spectator rather

than participant.

Whenever a problem arises,

the spectator asks,

"Why don't they do something?”

They can't help the police

to maintain law and order.

You can!

They are not responsible

for the conditions of your schools.

You are!

They can't give your community

good government.

You can!

Every civic group,

every business,

every sports club,

every good tradition,

every worthwhile institution

began with a need,

a vision

turned into a reality by someone

alive, responsible

and innovative.

To the people who sit back and

ask,

"Why don't they do something?”

we ask,

"Why don't you?”

*(Published with the hope that it will remind some readers of their basic responsibilities.)*