Humans across the globe have tattooed their bodies for at least 5,000 years. However, the archaeological evidence for these practices has been largely overlooked. In this article, archaeologist Aaron Deter-Wolf describes what drew him to the study of ancient tattooing, and how careful considerations of material culture, including artefacts and preserved human remains, are revealing new information about human bodies in the deep past.

I was first tattooed in 1998 in New Orleans, Louisiana, where I was a graduate student studying the archaeology of the ancient Maya. Those tattoos were drawn from my studies, based on the rich corpus of Classic Period Maya art that flourished in the Central American lowlands between about 200 and 900 CE. Within that tradition, the bodies of many humans and human-like supernaturals are shown decorated with glyphs and symbols. It is not clear if many Classic Period motifs — including the glyphs tattooed on my shoulders — were ever inscribed on actual human bodies in the past. Instead of being literal representations of tattooing, the placement of those motifs on individuals in the art historical record was likely a convention Maya artists used to indicate the identities or actions of their subjects. Regardless, it is widely understood that certain segments of ancient Maya society extensively marked their bodies with tattoos and scarifications created using obsidian blades.

Following graduate school, my archaeological career turned north, and for over two decades, I have worked on identifying, studying, and preserving pre-colonial Native American archaeological sites in what is today Tennessee and the southeastern United States. As I began working in this region, I was struck by the absence of tattooing from both scholarly discussions and popular perceptions of Native American lifeways. This was despite strong historical evidence that tattooing traditions existed throughout Indigenous North America before being nearly extinguished by Christian missionization and forced acculturation.

Just as in the Maya area, historical documents describe tattooing practices throughout North America at the time of European arrival. The Frenchman René Goulaine de Laudonnière recorded one of the earliest such accounts in 1564, in a description of Timucua people living near what is today Jacksonville, Florida. The term “tattoo” would not enter European lexicons to describe permanent designs on human skin until the 18th century, after adoption from Polynesian languages following Captain James Cook’s voyages to the South Pacific. Nevertheless, it is clear from Laudonnière’s description that the ‘beaux côpartimês’ on Timucuan bodies were tattoos rather than a temporary form of body marking:2

‘La pluspart d'eux sont peints par le corps, par les bras & cuisses de sort beaux côpartimês, la peinture desquels ne se peut jamais oster a cause qu'ils sont picquez dedans la chair.’ (Laudonnière 1586:4)

‘Most of them are painted on the body, arms, & thighs with beautiful designs, the paint of which can never be removed because they are pricked into the flesh.’

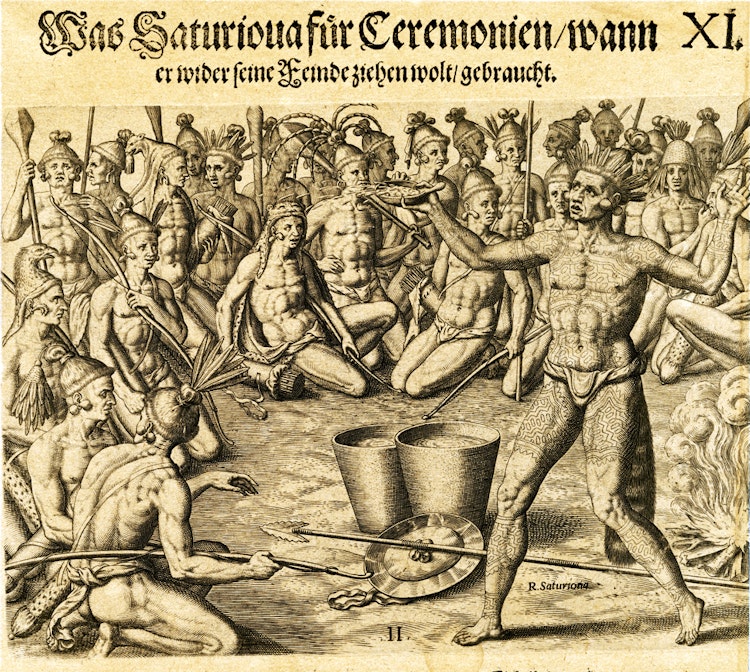

The tattooed Timucua leader Saturioua performs a ritual before leading a military expedition. This engraving from Theodore de Bry’s 1591 volume Grand Voyages is based on an original sketch by Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues who, along with Laudonnière, was a member of the French colony in Florida.

Similar descriptions of tattooed Indigenous bodies appear in numerous European historical documents throughout North America during the 16th through early 20th centuries. These records, along with the memories of Indigenous elders, demonstrate that tattooing was an important part of many — and perhaps most — Native American societies.

Indigenous tattooing in North America was not a recent phenomenon at the time of European arrival, but instead reflects cultural traditions extending into the deep past.3 All across the continent, pre-colonial artworks in ceramic, shell, stone, and other media depict markings on the bodies and faces of human and human-like individuals that may represent tattooing. In some cases, identical motifs appear hundreds of years later as historical tattoos in the same regions, demonstrating centuries of continuity.

Despite the prevalence of tattooing in the pre-colonial artistic record, historical accounts, and Indigenous cultural memory, it was not until the early 21st century that the practice was widely recognized as an important aspect of Native American cultural heritage. As I began examining the archaeological record for evidence of these traditions, I realized that similar discontinuities exist throughout the world between ancient body modification practices and modern perceptions of archaeological cultures.

Seeking the evidence

Evidence from comparative historical traditions suggests that the vast majority of tattooing in the deep past was not simply decorative. Instead, tattoos and the tattooing process were traditional cultural elements deeply connected to the construction of personal and group identity, and the orientation of the human body within both social and spiritual worlds. Depending on the culture and era, tattoos may have marked membership, empowered individuals by invoking and channeling supernatural forces, signified personal achievements and status, provided physical and metaphysical connections between individuals and their ancestors, served as therapeutic treatments, and in some cases acted as a means of punishment and dehumanization. Unfortunately, our specific knowledge of tattooing among most archaeological cultures remains fragmentary.

The science of archaeology seeks to understand people of the past through the examination of their material culture: specifically, the artifacts that people made, used, and left behind. Yet we cannot limit our understanding of the past to just objects, or even to their associated processes. Humans in both the past and present inhabit a framework of material and immaterial culture. The objects we make and use each day are physical creations that serve specific purposes. However, all of the material qualities of these items, including how, where, when, and by whom they are made and used, are conceived of and governed by systems of perception and belief.

The material culture of tattooing includes the tools, pigments, and other materials with which tattoos are created, as well as the bodies on which they are inscribed. The immaterial culture of the practice encompasses the social structures and cultural geography that inform how, where, and why individuals become tattooed, the meaning of tattoo motifs, and the internal and external perceptions of tattooed skin. If we are to truly understand tattooing in past societies, we must seek to connect the material and the immaterial. However, to understand the intangible, we must first be able to identify the physical. To this end, my studies have focused mainly on identifying ancient tools used for tattooing, and on recording actual tattoos preserved on human skin in the archaeological record.

Ancient tools

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, archaeologists would sometimes identify sharp artifacts as being possible tattooing implements. These identifications were rare, however, and before the past decade were based mainly on intuition rather than specific evidence. As a result, few early identifications of tattooing artifacts stand up to contemporary scrutiny. To responsibly suggest that an artifact was used for tattooing requires more than an impression of its relative sharpness. Instead, identifications of archaeological tattooing tools should incorporate multiple lines of evidence drawn from historical and traditional cultural knowledge, as well as physical data.

Ancestral Puebloan tattooing tool from the Turkey Pen site in southern Utah, dated 79–130 CE.

In 2017, my colleague Andrew Gillreath-Brown discovered an unusual artifact while cataloguing a collection excavated decades earlier at the Turkey Pen Rockshelter, an ancestral Puebloan site in southern Utah. Preservation at the site was remarkable, and the 2,000-year-old midden contained a variety of organic materials that seldom survive in archaeological settings, ranging from animal feces to individual strands of human hair. The artifact that Andrew identified was just under 10cm long and consisted of two cactus spines inserted into the end of a small twig that was bound with fiber. The final 2mm of both spines was stained with black pigment, and one was slightly shorter than the other, having apparently broken during use.

No identical artifacts had been previously identified in the region, and the function of the tool was not immediately clear. We believed that it might have been used to tattoo, based on the presence and extent of the pigment staining. To test this idea, we turned to both the historical record and techniques of archaeological science.

Historical documents, anthropological studies, and Indigenous knowledge record tattooing among numerous Native American groups in the American Southwest during the 16th through the early 20th centuries, including the Akimel O'otham, Apache, Cocopah, Hualapi, Havasupai, Kwatsan, Mojave, Ute, and Pueblo. In the region surrounding the Turkey Pen site, cactus spines were the primary traditional implements for putting ink into the skin, and were so effective at tattooing that they continued to be used for hundreds of years after the colonial introduction of metal needles. Historical accounts from that region overwhelmingly describe tattooing with spines from prickly pear cacti and pigment made from wood charcoal. Careful examination of the Turkey Pen artifact allowed us to identify the various plant species used to construct the tool, and confirmed that the spines were indeed those of a prickly pear. Elemental and microscopic analysis showed that the black residues on the tips of the spines were carbon pigment, and revealed microscopic charcoal grains embedded into the surface of the spines in that area.

It may seem counter-intuitive to consider our bodies as ‘material culture’, thereby placing humans into the same category as everyday objects. Yet our bodies, like our tools, are cultural constructs.

‘Experimental archaeology’ is a process of learning by doing. Recreating and using tools from the archaeological record, and careful documentation of the process, allows archaeologists to better understand how actual artifacts were made and used in the past. In our study of the Turkey Pen artifact, we gathered materials from the same plant species and assembled them into replica tools which we then used to tattoo pig skin with a charcoal-based pigment. High-powered microscopes revealed that the tattooing process resulted in a series of distinct physical changes to the spines of our replica tools. These included stripping of microscopic barbs from the surfaces, rounding of the tips, and embedding of charcoal grains, all within the final 2.5mm of the spine tips. All of these distinctive traits were also present on the spines of the original artifact. During testing, a spine on one of our replica tools even broke in exactly the same manner as seen on the original.

By combining historical and archaeological evidence we were able to confidently identify the Turkey Pen artifact as a tattooing tool. The artifact was recovered from layers radiocarbon dated to the first century CE, demonstrating for the first time that Indigenous tattooing in western North America extends back nearly 2,000 years before the present. However, the specific meaning of tattooing for Ancestral Puebloan residents of the site remains unclear. Historical data and traditional knowledge from the American Southwest show that, millennia later, the timing, recipients, and meaning of tattooing traditions varied by group. Tattoos variously marked adulthood, were applied as part of mourning rituals, invoked spirit guardians, were believed to aid in conception or slow the effects of aging, and granted souls of the deceased access to the ancestral realm. The archaeological origins of the Turkey Pen tool within a midden reflect the moment at which it was last used and discarded, and so provide little information for understanding the immaterial culture of the associated Ancestral Puebloan practice. Before we can cross that divide, we will need more data.

Tattooed mummies

It may seem counter-intuitive to consider our bodies as ‘material culture’, thereby placing humans into the same category as everyday objects. Yet our bodies, like our tools, are cultural constructs. Social processes including nourishment, disease, medicine, shelter, and violence all shape and refine our bodies, beginning before our birth and continuing throughout our lives. After death, our physical remains, and the manner of their burial or disposal, present a record of lived experiences.

It is rare for human skin to survive in the archaeological record. Those examples that exist are the result of unique arid or anaerobic environments, sometimes supplemented by deliberate cultural practices. Preserved archaeological individuals — mummies — represent only a bare fraction of the total human lives in the past, and yet because of their preservation can teach us an incredible amount about both individuals and cultures.

Modifying the natural body, whether temporarily or permanently, is a universal behavior among human societies of the past and present, and archaeological evidence shows that tattooing has existed in societies all across the globe for at least the past 5,000 years.

American tattoo artist Samuel Steward wrote that when asked about how long tattoos would last, he always answered: ‘Guaranteed for life — and six months.’ There are exceptions to every rule, and tattoos have survived for centuries on preserved remains from archaeological sites across the globe. In the Tattooed Human Mummy database, I have compiled information on preserved tattoos originating from nearly 60 archaeological sites, including locations in western China, Siberia, the Nile Valley, Greenland, Hawai’i, the Philippines, and more. Hundreds of additional preserved tattoos are located in archaeological sites and museum collections around the world but have not been published or fully documented. Identifying these remains is important to understanding the geographic and temporal distribution of tattooing practices, identifying the motifs associated with different cultures, investigating who is tattooed in specific societies, and assessing how their tattoos were created.

The oldest and most famous ancient tattooed human is the man from the Alps known as the Iceman, or ‘Ӧtzi’, who was entombed beneath glacial ice ca. 3200 BCE during the European Copper Age. However, the greatest concentration of preserved ancient tattoos identified to date is found in the Pacific coastal deserts of Peru and northern Chile. In that region, tattooing took place over at least 4,000 years among cultures including the Chinchorro, Moche, Chimú, and Chancay. I have recently been fortunate to work alongside colleagues documenting several hundred examples of preserved ancient Andean tattoos in the collections of American and European museums.

Our research on Andean tattooing relies heavily on digital imaging technologies including infrared and multispectral photography. These techniques are effective because tattoo pigments absorb certain wavelengths of light differently than untattooed human skin. Imaging equipment that record those spectra therefore can reveal tattoos that are faint, or even invisible to the naked eye. As a result of the refinement and increased availability of these technologies, more preserved tattoos have been identified on archaeological remains during the last decade than in the entire previous century.

Our studies, which are still being prepared for publication, reveal significant new information on Andean tattooing traditions and their connection to other forms of material culture. For example, through close examination of the physical structure of preserved tattoos, and comparisons of those characteristics with the results of recent experimental studies, we can assess the techniques and tools likely used to mark skin in the ancient Andes.

Historical and modern tattooing traditions frequently incorporate multiple tool arrangements to address different stylistic needs, such as lining and shading. It is unusual however for a single culture to employ multiple tattooing techniques. Our examinations show that multiple techniques were used in the ancient Andes, in some cases within single tattoos. Some tattoos from the region are composed of groups of short lines with hard edges and tapered ends, both evidence of being incised into the skin with a sharp blade. Other examples exhibit the telltale stippling of direct puncture (also known as hand poke) tattooing using a tight cluster of small points consistent with bundled cactus spines.5 Some Andean tattoos were created by outlining shapes and then filling them in, similar to modern techniques. However, in other instances, figures are formed entirely by sequences of parallel tattooed lines, reminiscent of how patterns are constructed in the weft of preserved weavings from the region.

Tattoos on the left arm of an ancient individual from coastal Peru, extending from the shoulders to the back of the hand. Different patterns are present on the interior and exterior surfaces of the forearm. Based on their style, the tattoos likely date ca. 1000-1200 CE.

Most of the Andean tattoos our team has documented to date come from collections with little information as to their original archaeological context, and aside from the style of the tattoos, we often have no evidence with which to assign them a date or cultural affiliation. Nearly all are incomplete and have been disassociated from any artifacts that may have originally accompanied them, and as a result, the biological sex and social status of the tattooed individuals cannot be determined. These issues are unfortunately all symptomatic of late 18th- and 19th-century collections. While we cannot correct these mistakes of the past, we hope that documenting the tattoos on these remains will help build an awareness of, and interest in, the richness of these traditions.

Looking ahead

Modifying the natural body, whether temporarily or permanently, is a universal behavior among human societies of the past and present, and archaeological evidence shows that tattooing has existed in societies all across the globe for at least the past 5,000 years. Despite recent achievements in expanding our knowledge of these practices, the archaeological study of tattooing is still in its infancy. Substantial work remains to be done investigating the physical evidence of tattooing before we can begin to truly understand the immaterial culture and importance of the many ancient traditions. Tattoos preserved on remains from archaeological sites throughout the world show the extent and diversity of tattooing practices; yet we do not know what tools or pigments most cultures used to create those marks. In other instances, identifications of tattooing artifacts reveal traditions dating back at least 3,000 years before the present; yet we know almost nothing about the associated motifs. In either case, there is little evidence for determining who in these societies became tattooed, the reason(s) for their marking, the identity of the tattooist, the significance of the marks, or how their tattoos were entwined with other material and immaterial cultural traditions. Changing this situation will require the use of new technologies, reexaminations of existing collections, and willingness to challenge conventional perceptions of how human bodies looked in the past.