In this essay by Julia Wild and Katharina Dettar, we are invited to contemplate jewellery as a means of communication, directed both inward and outward. Taking the wedding ring as an example, Wild and Dettar investigate its significance in relation to identity, status, materiality, absence, and loss.

Jewellery is a sign placed on the outer layers of our identity – our skin or clothing. It is an extension of our being, a link between the inner self, body, and our social environment. To reinforce the expressive side of the subject at the centre, people across cultures place objects at the boundary of their physical being. Therefore, jewellery becomes a means of communication that is directed both inward and outward.

Like a star in orbit, the jewellery object refers to the centre, the wearer. At the same time, it unfolds its effect to the outside, whereby the readability of the sign can change depending on the inner attitude of the wearer, the context in which the jewellery piece is worn, as well as the frame of reference of the observer. Its radiance or higher meaning can be visible to all or perceived by only a few, unnoticed by one, perceived as meaningful to another. This orbital character of jewellery is most vividly demonstrated by the wedding ring. It has been worn in Western culture for centuries as a sign of the union between two people, and generates a broad spectrum of the symbolic meaning and readability of jewellery. Jewellery does not have a single unique meaning, but many potential connotations.

Through its materiality, the ring refers to the nothingness which it encircles when not worn. It creates a space in the void, and is both cohesion and demarcation simultaneously. The ring is an archetype representing an orderliness, setting itself apart from an amorphous nothingness. On the one hand, the ring depicts the cycle of nature; on the other, it stands for the ordering force which gives a form to material, the primordial matter. This makes it an ambiguous symbol for the regularity of the cosmos – a term that in ancient Greek (κόσμος) not only denotes the universe and world order, but also jewellery.

If the ring is worn, the void filled, then it is a piece of jewellery closely encircling the finger. The physical proximity to the body also creates a symbolic proximity to the wearer. It becomes a part of the person’s physical appearance, or to some extent a reference to their personality.

The ring marks a boundary between the wearer’s person and their environment. It is a boundary marker that can act inwardly as well as outwardly, reminding the wearer of an event, promise, or a relationship, and simultaneously reporting on their tastes, status, or affiliation to those around. In the case of the wedding ring, it signals the status of being married, while reminding the wearer of the ritual that accompanied the acquisition of that status, and the lingering promise. The symbolic content, however, goes beyond the personal, in that it testifies to the ritual and legally relevant act of marrying in front of a community.

The wedding ring encloses the ring finger and becomes an extension of one's body. By being worn, it mirrors the course of one's life, and changes along with the wearer: the ring sits tightly or loose on the finger, it becomes thinner and more fragile through the mileage of a lifetime. As a sign placed on the outer sphere of the wearer´s appearance, it communicates to the beholder the status of the wearer – married or not, rich or poor. But it also speaks to the wearer. The conscious act of looking at it evokes a memory, and a promise is visually recalled. Its materiality, the feeling of the heaviness or lightness of the ring, also subtly "communicates" with the wearer, who often becomes aware of the ring's existence only when it is not there; they have put it down or the ring has been lost. The absence of the ring makes its previous presence even more noticeable.

This absence can be consciously controlled by the wearer. In putting the ring on or taking it off, the wearer makes visible the status of the relationship, and symbolically expresses both their external and internal attachment.

Absence can also mean loss. Absence, often perceived as emotionally painful, shows the multifaceted value of the ring, which goes far beyond its material value. The lost wedding ring becomes a sign of being adrift and no longer connected. If we look at the stories that revolve around the loss of wedding rings or even the finding of them again, the significance of this sign becomes apparent: the wedding ring represents not only a person, but a sense of belonging, whether to a person, or a community.

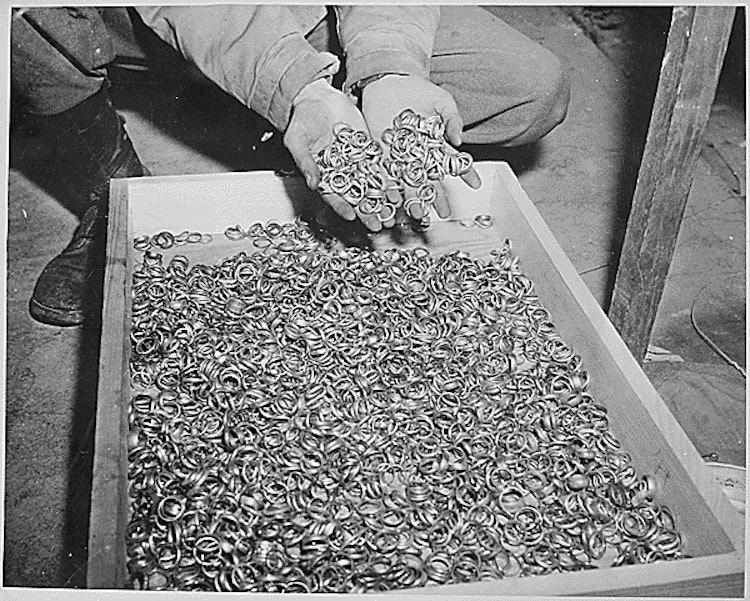

This significance of the wedding ring can be seen in Denmark's handling of refugees' valuables: in 2016, the Danish parliament debated whether and to what extent valuables should be taken from refugees. The wedding ring and cell phone were explicitly excluded from this. Both are strong signs of connection to other people: the cell phone on the functional plane, the wedding ring on a symbolic level. The inhumanity of a practice that takes away a person's wedding ring was underlined in the discussion with reference to the actions of the Nazis. In concentration camps, prisoners were deprived not only of all valuables, but of everything that identified them as an individual. Not only did the Nazis enrich themselves through this procedure, but they tried to visually objectify the prisoner. The images of the piles of methodically sorted wedding rings from concentration camps touch the viewer, because the symbolic value of the wedding ring is so apparent. In this case, it is not their absence on the skin that is felt, but the absence of the people who wore those rings.

This absence in the presence of a worn ring is also palpable in Otto Künzli's necklace, which consists of 48 wedding rings. It poses the question: what became of the couples who wore them? The hope that underlies the marriage vows of wanting to be together forever? Why are they no longer worn? Have the wearers died, divorced? The wedding ring, which should remind the wearer of the event of the wedding, loses this memory function through its absence. This goes hand in hand with a feeling of wearing a foreign intimacy with Künzli's chain. Traces of use can be seen on the wedding rings; they carry the existence of the former wearer, but this intimacy is torn from its original context.

The special aspect of the ring is that, unlike most other forms of jewellery, it can also be looked at by the wearer and direct its sign character value to them. This particular visual positioning makes it a very personal piece of jewellery. Thus, by touching and looking at the ring, the wearer can evoke memories which are inaccessible to those around them. This brings about an internal dialogue, making the ring an instrument of self-assurance.

In the case of the wedding ring, too, a shift of the symbolic function away from indicating status or group membership towards stabilising one’s own history and self-perception is apparent. In addition to the ring as a symbol of the moment of marriage, people also wear wedding rings that belonged to their parents or an ancestor. It is no longer a sign of connection to a spouse, but to a loved one, usually deceased. A symbol that was previously easy to decipher in the Western world has been transformed into something that can no longer necessarily be read immediately by a wider social circle. The wedding ring loses its expressive value about social status – unmarried or married – to an intimate object whose commemorative value is apparent only to the wearer.

A piece of jewellery, even a wedding ring, can function as an amulet by connecting the wearer to a system of symbols, which creates a feeling of resonance in them. This can be a strong bonding agent within a community, and also towards the inanimate environment. The ring becomes a medium of communication between the materially tangible and the transcendental world.

By recalling the moment of marriage or a person who wore the wedding ring, the ring itself, whether as a sign of being married or as an inherited jewellery object, becomes a means of self-strengthening. It becomes an amulet to support or guide the wearer through the remembrance of a person or a difficult situation. This is also what makes the loss of the wedding ring as a sign of attachment so significant to a person in times of crisis.

Jewellery, and by extension the wedding ring, are still markers of status today. Not only does it indicate economic wealth, jewellery also testifies that something may have changed in the social structure. It is therefore an important part of many ritual processes in which a change of status is embedded. Societies are structured through these ritual processes. Jewellery takes on the function of making this change of status visible. It is an indicator of the person's position within a community.

Marriage is a rite of passage that indicates that the future partners will leave their families and start their own family. This also changes the married couple's status in society. In Western culture, this has been made visible for thousands of years in the wearing of a wedding ring. It is a sign of togetherness, but also indicates the partner's occupation, the claim of ownership.

The famous engagement ring by Tiffany, which was already developed in the 19th century, symbolises both prosperity and the change of social status are symbolised. Through its simple structure, which places the diamond at the centre, it becomes a testimony and measure of the supposed truthfulness of love. It links an emotional value with the size of the material. The larger the diamond, the truer and greater the love of the man giving it. In this way, the woman who receives the gift ultimately also becomes the object of the observer's evaluation: how much was her husband willing to invest? But it is also an indicator of the man's wealth. By wearing the ring, his materialised love, the woman becomes the man's extended piece of jewellery.

One can connect to another person through jewellery – placing oneself in a new context. ‘With this ring, I vow to love and honour you from this moment onwards.’ The individual presents themselves as part of a larger community, extends the expression of their self through the object. The piece of jewellery can thereby testify to an event or a togetherness. It thus becomes a link to the outside; in the case of the wedding ring, to the beloved person. In addition, it also establishes the connection with the community that witnesses the union. Not only in the verbal act of communication accompanying the ceremony, but also, in the engravings, ideas of love and commitment are communicated that not only concern the individual, but relate to the context of values carried by the community. It also bears witness to a superior value system in the context of which the wearers wish to place themselves, be it eternal love and fidelity or, in the religious context, God, who is invoked as a witness, as for example the wording in the Roman Catholic ceremony shows: ‘Take this ring as a sign of my love and fidelity. In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.’ When relationships come to an end, there is often a need either to stop wearing the jewellery as a symbol of that connection, or even to destroy it. as in recent trending Japanese divorce parties, which are a reversal of the wedding, with guests, bride and groom, and a party inwhich the ring is smashed with a hammer as the climax.1

A ring is a circle, with no beginning or end. A sensually experienceable image of the cyclical recurrence of natural processes, and thereby one of mankind’s oldest symbols for renewal and infinity. This cyclic experience of time and change plays a major role in religious and increasingly also in secular rituals, through which a change or crisis in life is transformed into everyday normality. A marriage ceremony is an example of such a change that affects the lives not only of the lovers, but also of those around them. The wedding ring becomes the appropriate piece of jewellery to witness this because its round, closed shape symbolises infinity and indissolubility, even if this is not necessarily fulfilled. Nevertheless, even in its loss, destruction, or reinterpretation, it speaks of what jewellery means to us as human beings: it is a phenomenon that results from social processes, is shaped by them, and materialises through them. By becoming visible, these social processes can be discussed, changed, reshaped, or even destroyed in further steps by the community that produced them. Just as society is subject to change, jewellery is also subject to an ongoing discourse that changes it in its meaning, form, and materiality. The only part that remains unchanged is its orbital relationship not only to the human body, but also to the inner self.