Courtesy of The Noa Eshkol Foundation for Movement Notation, Holon, Israel, neugerriemschneider, Berlin, Germany, Gladstone Gallery and Oslo Kunstforening, Norway

Arlyne Moi

In December 2021, Mooky Dagan, the chairman of the Noa Eshkol Foundation, met with Marianne Hultman, the curator and artistic director of Oslo Kunstforening, Anne Dressen, the curator of contemporary art at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, and Lars Sture, the curator at Norwegian Crafts, to talk about the wall carpets of Dagan’s long-time friend, the dancer, choreographer, artist teacher and researcher Noa Eshkol.

You can save this interview as a pdf, send it to an email, or print it here.

Last year Marianne Hultman curated the exhibition Noa Eshkol: Rules, Theory & Passion together with Helena Scragg, the curator at Norrköping Art Museum. The exhibition, that will travel to Norrköping this spring, is produced by Oslo Kunstforening, Norrköping Art Museum and Jewish Culture in Sweden. Noa Eshkol: Rules, Theory & Passion

also includes works by the artists Yael Bartana, Omer Krieger and Sharon Lockhart. In 2013–14, Eshkol’s work was included in Decorum, Carpets and Tapestries,

a seminal exhibition on textile art curated by Anne Dressen at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris and at the Power Station in Shanghai.

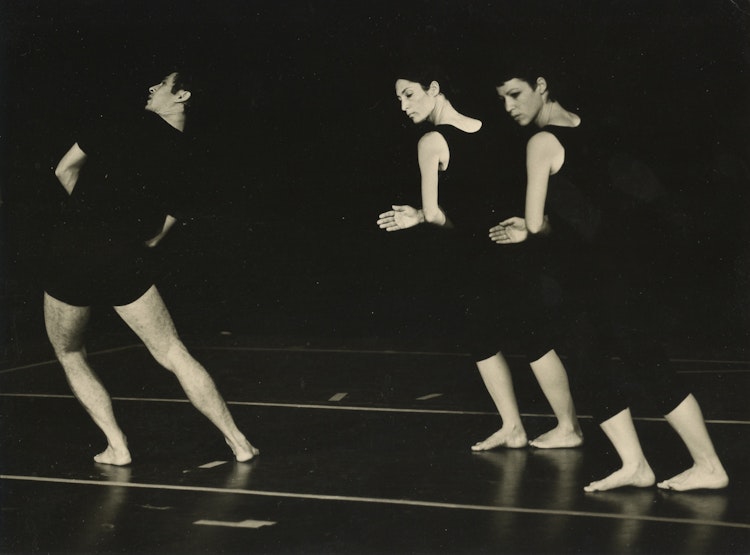

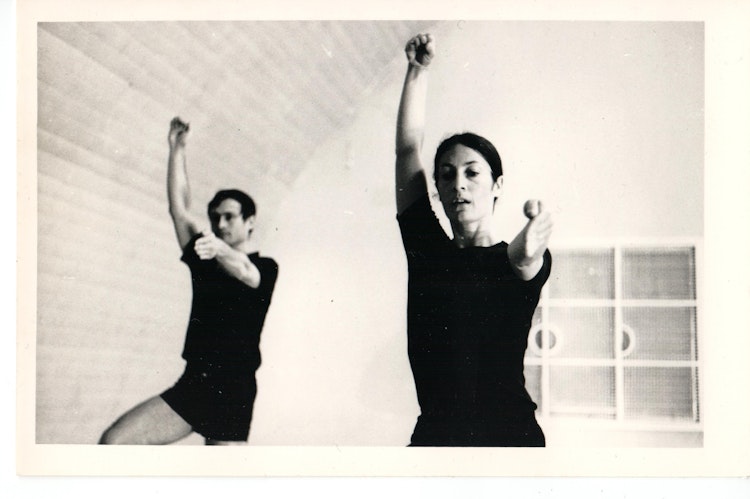

Noa Eshkol (1924–2007) began her professional career in the 1950s as a dancer, choreographer and theorist. In 1943, after taking piano lessons as a child, Noa Eshkol enrolled in the Tehila Rössler Dance School in Tel Aviv. While there, she was introduced to Labanotation, a notation system for movement created by the dancer, choreographer and theorist Rudolf von Laban. Inspired by this, Eshkol went to Manchester to study under Laban at the Art of Movement Studio. While in the UK, she also studied at the Sigurd Leeder School of Modern Dance in London. In 1951, Eshkol returned to Israel and three years later founded her own dance group.

Music was the basis of Eshkol’s work; she referred to herself as a composer, and many of her pieces have titles such as Suite or Etude. Her choreographies are reminiscent of music wherein each limb of each dancer can be likened to an instrument in an orchestra. Just as orchestral music is notated, Eshkol wanted to establish a universal notation system for movement, so that each movement could be precisely represented.

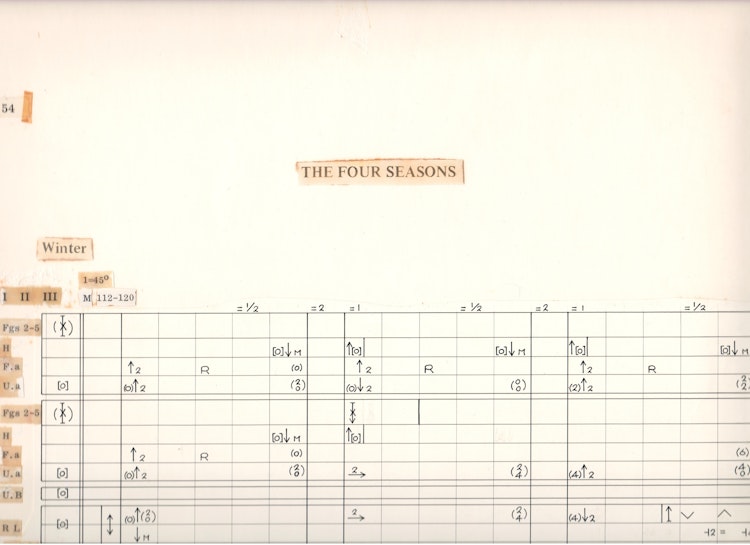

In 1954 she founded the Chamber Dance Quartet in Holon, outside Tel Aviv, Israel. In her quest to precisely capture and analyse movement of the body, she created Eshkol-Wachman Movement Notation (EWMN) together with her pupil, the architect-to-be, Avraham Wachman. The first textbook on EWMN, written together with Wachman, was published in London in 1958. This ground-breaking system, like music notation, is used for both documentation and communication. But rather than capturing musical tones and rhythms, it represents physical movement. The system could also be used beyond dance, as a common notation device in zoology, psychology, neurology and medicine.

In 1968, Eshkol founded the Movement Notation Society in Israel. Four years later she established and headed the Research Center of Movement Notation at the Faculty of Visual and Performing Arts at Tel Aviv University. In 1984, she organised the first International Congress for Movement Notation.

In the early 1970s, Eshkol began creating textile works that she called wall carpets, assembled from offcuts and rags. These wall carpets, like her dance pieces, are the result of cooperative effort.

From left to right: The First Carpet, 1973 cotton, silk twill, rayon crepe, rayon taffeta, synthetic jersey, pearl button 209 x 138,5 cm. Mourning Carpet, 1974 wool, woollen flannel, woollen tweed, cotton, synthetic jersey 170 x 155 cm. Yellow Landscape (Homage to Van Gogh), 1979 cotton, wool, silk, viscose, rayon, polyester, polyamide 232 x 137 cm. Courtesy: The Noa Eshkol Foundation for Movement Notation, Holon, Israel, and neugerriemschneider, Berlin.

Marianne Hultman (MH): Noa Eshkol made her first wall carpet in 1973 during the Yom Kippur War. One of the members of the chamber dance group, Shmulik Zaidel (Shmuel), was called up to serve in the war, so the group practice came to a halt. During this uncertain time, Eshkol developed a new practice. She gathered all the textile scraps she could find at home, sat on the floor and started to assemble the bits and pieces.

Anne Dressen (AD): Somehow, the context surrounding the making of The First Carpet (1973) reminded both Marianne and I of Penelope’s wait in Homer’s Odysseus. During her husband’s long absence after the Trojan Wars, suiters from Ithaca and nearby islands began to court her. She insisted that they wait until she had woven a shroud for Laertes, Odysseus’s father. Every night she unravelled the piece that she has woven by day, not giving up hope for the return of her husband. Do you think that for Eshkol, the making of wall carpets functioned as a kind of survival-and-resistance tool during the Yom Kippur War?

Mooky Dagan (MD): At the beginning it was very innocent, in the sense that it was about having something to do to fill her time. I was abroad when the war broke out. When I finally managed to return, I called Noa to see how she was doing. The conversation was grim, the war was a catastrophe. After sharing the most important updates, she told me that something very strange had happened to her: ‘I don’t know how to explain it, but I started doing these carpets’, she said. They had stopped dancing, but the dancers still kept coming every day. At that time, there were three members of the chamber dance group, Racheli Nul-Kahana, Ruti Sela and Shmulik Zaidel. Others who used to come on a daily basis were Tirza Sapir and Michal Shoshani. In order to have something to do, she took an old blanket and some pieces of fabric that she had at home and put them together in a composition. It was about occupying her hands with something, in order to pass the time. She needed something to distract herself from the horrible situation of the war. And she found in it some kind of relief. So to romanticise it in the sense of imbuing it with any deep or profound meaning would be incorrect. Later, when it developed, of course, other things came into it, but at the beginning, it was really something to keep herself busy as well as the two or three dancers or pupils who were around her.

Noa Eshkol loved materials. As a pastime, when she wasn’t busy with her notation or teaching, she used to make necklaces from beads. She liked doing things with her hands. And she loved to dress beautifully, although she hardly ever went out. When she was young, she was interested in clothes, and she always appreciated good materials. That’s how she ended up having fabrics at home. She collected them like she collected beads.

After making the first few carpets, people started bringing her remnants of fabrics. She also got remnants from the clothes workshops at the kibbutzim. In addition to that, we started going to southern Tel Aviv at night to pick up off-cuts from the clothing workshops located there. Many symmetrically shaped pieces from the same fabric were found there. She was very much intrigued by that, since her world in movement also had to do with symmetry. The amount of raw material was enormous.

Being the analytical person that she was, she made strict rules for herself right from the start. She only used castoffs, and she never cut or altered them. She didn’t use patterns with human figures or animals printed on them. But she did allow herself to undo pieces of clothing. Sometimes you can see something that used to be part of a sleeve or a pair of trousers. Some of the carpets include a circle, and you can see that it used to be a skirt, or an umbrella.

With movement, she discovered the system and the ability to analyse. But with the wall carpets, she never discovered a system; it was something completely emotional. She couldn’t explain it. ‘I don’t do anything’, she said, ‘it’s the material that dictates to me what to do.’

MH: Noa Eshkol made the compositions for the wall carpets. I read somewhere that she made around 1,800 of them. If she started making them in 1973, and she passed away in 2007, that makes 34 years. That would mean she made 52 carpets per year. That’s quite an achievement considering that it wasn’t her only occupation. But as you say, the sewing of them was mostly done by others.

MD: In the beginning she was also sewing. She made at least one carpet per week, so after a while she couldn’t catch up. A couple of the dancers and I started helping her with sewing. The division between the creative part and the making was absolutely clear. It wasn’t a communal work, by no means. She made the compositions. She attached the pieces of material to the background with pins. The sewing was a technical thing. It was the same with the movement. ‘Everybody can and should dance. But not everybody can dance my dances’, she said.

MH: Noa Eshkol made wall carpets in all sizes, some of them monumental. Does their size match the size of the floor in the room where they were made?

MD: The size of the room was significant, as were the background materials. The first ones were military blankets, and then she got bed covers and curtains. At times she used to sew two bed covers together to make a larger background. She made most of her wall carpets in a room next to the kitchen. But when she got very big backgrounds, she had to move to the dance studio. There are two carpets that are 5 x 5 meters. They’re the largest. The backgrounds came from the Israeli Air Force. Enormous pieces of canvas. When she got them, she was of course thrilled by the sheer size of them. She loved to do the large-scale ones. But sometimes when she had no time, or in-between, she did very, very small ones, which are like little jewels.

AD: Did Noa Eshkol give titles to all her wall carpets? The titles are specific but still open for interpretation. Some point towards the history of painting, and in this way, they pull away from the more abstract carpet tradition.

MD: Noa Eshkol gave all the titles. She was a very cultured person; in literature, in visual art, in music. Her library had books on everything from ancient Egyptian and Etruscan art all the way to Rothko and Pollock. She made works that paid homage to Hockney, Derain, Klee and the Impressionists. But again, she didn’t sit and think, ‘Now I’m going to pay homage to David Hockney’. She made something, and after it was finished, it reminded her of him. At some point, she gave up on given titles. The ones that she didn’t name, I titled Untitled because I don’t presume to speak in her name.

MH: Noa Eshkol seemed to have quite a few people of influence around her. She was also the oldest daughter of Israel’s third prime minister, Levi Eshkol. At the same time, she wanted to be independent, as you say. How did that work out?

MD: She didn’t take advantage of the fact that her father was prime minister, and he wouldn’t let her either. You must remember that Israel was different in those days compared with the political life of today. And parents in those days were not very involved in the lives of their adult children. It’s difficult to understand the mentality of people like Eshkol. She hated the establishment and she didn’t want to have anything to do with it, and her father never understood what she was doing. He was supportive in the sense that he loved her dearly. He had three more daughters, Noa’s half-sisters. And Noa, of course, grew up with her mother after her parents separated when she was young. Her mother, Rivka Marshak, was a very independent woman who died early, in 1950. But you’re right in saying that Noa was surrounded by influential people. People were fascinated by her. Noa was a greatly admired, mysterious and a controversial person.

MH: From what I understand, she gave a few wall carpets to friends and family members, but she never sold any of them. What do you think about the recent interest from the art market, and from institutions around the world? Is this contradictory to her own vision?

MD: She was ambiguous about selling. Her work was not commercial. She received minimal support from the Ministry of Education. At one point we managed to convince her to let someone buy one of her wall carpets so that she would be able to publish a book. But after a couple of years, she demanded the work be returned to her. In her will, however, she specified that the carpets should be sold in order to finance the foundation. And this is how – with great difficulty – we managed to survive. A major change happened when the gallery in Berlin, neugerriemschneider, saw the greatness of the wall carpets, and of her whole person as an artist. This was totally unexpected. The gallery brought her into the world market and museum collections.

From left to right: Heavy Soil Fields, c. 1980 wool, cotton, rayon 300 x 196 cm. Insects in the Sun, 1990 cotton, synthetic fibers, lurex, rayon 278 x 216 cm. Vase with White Apples, 1997 cotton, wool, silk, cotton-linen, twill, percale, tulle 258 x 175 cm. Courtesy The Noa Eshkol Foundation for Movement Notation, Holon, Israel, and neugerriemschneider, Berlin Photo: Jens Ziehe, Berlin.

MH: How were her wall carpets first received?

MD: For years she refused to show them in public. Maybe four or five carpets would hang in the dance studio. That was the maximum. At some point, in spite of her own belief, she agreed to an exhibition, to be able to see them properly. That’s how she ended up having her first show at the Helena Rubinstein Pavilion for Contemporary Art at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art in 1978. On the one hand, she was very modest about what she was doing, and on the other, she would never agree to compromise about her work.

The exhibition drew crowds that the museum had never seen before. But the critics were terrible. The works were described as handicraft, old women’s hobbies. In addition, the Israeli art scene weren’t very welcoming. They complained: ‘How come Noa Eshkol, known for her work in dance and movement, and a great persona in that field, gets to do a solo show at the museum? She is not an artist.’ Some of her artist friends wrote her horrible letters. It was tempting to place her work in the categories of women’s art or folk art. I think it’s important to put it in the right framework, which is (fine) art. But of course, there were also people back then who already understood the greatness of what she was doing. Anyway, today the mood has changed completely.

MH: The artist Sharon Lockhart became the catalyst for bringing the wall carpets and movement together. Lockhart is interested in folkdance. Eshkol took great interest in the folkdance traditions in the region, and together with Shmulik Zaidel, she studied and learned different dances on location and then documented them with EWMN. For the video installations Four Exercises in Eshkol-Wachman Movement Notation and Five Dances and Nine Wall Carpets by Noa Eshkol, both from 2011, Lockhart worked closely with four members of the chamber dance group, Ruti Sela, Rachaeli Nul Kahana, Noga Goral and Mor Bashan, as well as with the team at the foundation.

The exhibition at Oslo Kunstforening (2021) and Norrköping Art Museum

(2022) includes wall carpets and archival material consisting of

photographs, drawings, research material and books, as well as works by

the contemporary artists Yael Bartana, Omer Krieger and Sharon Lockhart,

all of whom have made works inspired by Noa Eshkol. To my knowledge,

this is the first time that works by contemporary artists are

incorporated into one of her retrospective exhibitions.

Sharon Lockhart: Models of Orbits in the System of Reference, Eshkol-Wachman Movement Notation System: Sphere Four at Two Points in Its Rotation, 2011, two framed chromogenic prints 50 x 39.7 cm each © Sharon Lockhart, 2011, courtesy the artist, neugerriemschneider, Berlin, and Gladstone Gallery.

AD: Do you think Noa Eshkol would have appreciated how her research practice and wall carpets have been presented since she passed away?

MD: When Sharon Lockhart came to Holon she fell in love. From my point of view, she grasped the importance of Noa’s work – both in the field of movement and with the wall carpets – and I think she did Noa justice. Her project is quite beautiful. But Lockhart’s work would not have been possible if Noa had been alive. Noa would not have allowed any kind of interpretation.

MH: Because Noa never mixed the wall carpets with the other work.

MD: Never, never. She wouldn’t allow it. During her lifetime, on the very rare occasions when she had performances with the chamber dance group, there was the question of whether she should hang carpets in the background. But she always refused. On the other hand, when they were practicing in the dance studio upstairs, there were always carpets hanging on the walls, because this was the only place where there was room for them. So, if people came to the house, they did in fact see them together with the movement compositions. But never in public performances.

MH: As wall carpets, they relate to a flat surface and can be read as attempts to schematically represent, translate or transform three-dimensional form to two dimensions. Can it be said that the wall carpets at least to some extent become an experimental analysis of the body and movement? Seen from this perspective, they would not be opposite to the rest of her work, but truly related to it.

MD: It is an intriguing proposition because they’re the opposite aspects of the same person. I don’t wish to speak in her name, but what I can tell you is that for her, they were two totally separate worlds. She invented her movement notation because she couldn’t understand how people could organise movement without a mode of composition. She worked in a precise way, digging into details until she was able to crystallise every thought. This is an analytical and cerebral approach to movement that she was able to explain and teach. With the wall carpets, however, it was exactly the opposite, it was totally emotional.

At the same time, it’s important to understand that there was no

hierarchy. For her, there was no such thing as a beautiful movement:

there

was only movement. In this respect, she was rebelling against the world

of dance. With the fabrics it was the same thing. There were no

beautiful or ugly fabrics, no expensive versus cheap materials. On the

contrary, she said she could ‘take the ugliest pieces of material and do

something beautiful with them’.

About the Noa Eshkol Foundation for Movement Notation

The Noa Eshkol Foundation for Movement Notation was established in 2008 according to the will and testament of Noa Eshkol. It is located at Eshkol’s historic home in Holon, Israel, which was – and still is – the centre of collaborative study on Eshkol-Wachman Movement Notation (EWMN) and Eshkol’s dance repertoire.

The foundation sees to the conservation and accessibility of the Noa Eshkol Archive, a resource of primary source materials on EWMN and the history of the Noa Eshkol Chamber Dance Group. Its mission also includes the task of promoting academic scholarship on EWMN, the care and sale of hundreds of wall carpets made by Noa Eshkol, and the support of the Noa Eshkol Chamber Dance Group. The foundation initiates movement workshops, performances, lectures, consultation and assistance in EWMN, as well as exhibitions and special projects.

In her time, Noa Eshkol and her colleagues worked under the umbrella of the Movement Notation Society, an organisation that Eshkol founded in 1968. Today, the Noa Eshkol Foundation for Movement Notation is the only authorised organisation to carry out Noa Eshkol’s expressed wishes concerning her legacy.